Shipwrecked conquistador’s 4,000-km tale makes for desert-island reading

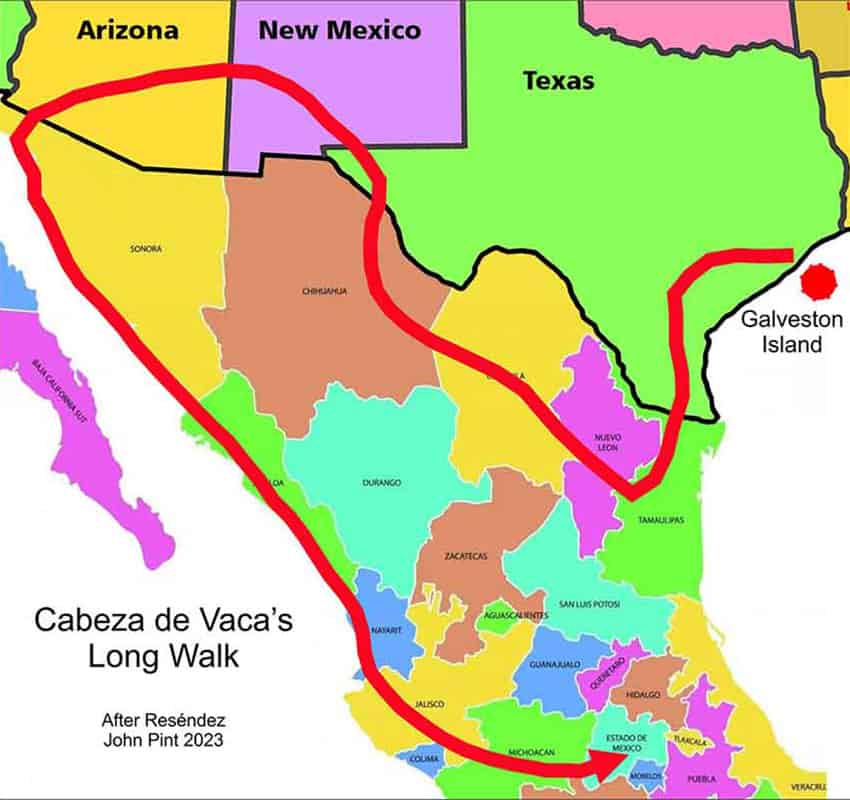

Between 1534 and 1536, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, a conquistador who never conquered anyone, walked nearly 4,000 km across the American continent and lived to tell the tale.

And he told it well. His story, “Naufragios y Comentarios” (Shipwrecks and Commentaries), makes for fascinating reading. Even more fascinating is the retelling of Cabeza de Vaca’s story by Andrés Reséndez, a Mexican-American history professor at the University of California, Davis.

His book, “A Land so Strange, the Epic Journey of Cabeza de Vaca,” was published in 2009 and adds much needed clarification, annotations and insights to this bizarre story, resulting in a narrative so curious, compelling and fluid that one of his readers declared that this was “one book I would take to a desert island.”

Cabeza de Vaca was the royally appointed treasurer of an expedition meant to establish a colony of Spaniards in Florida. In 1527, 300 of them set sail from Spain, only to suffer a most amazing series of mishaps.

Hurricanes, shipwrecks, near starvation and the bungling of an incompetent navigator landed the survivors on what is now Galveston Island, Texas, where their chain of catastrophes culminated in the desperate construction of a huge raft, upon which they piled absolutely everything they had (including their clothes and shoes).

When they pushed the raft into the sea, it broke up and sank, leaving 80 survivors who were very literally naked and barefoot and freezing to death.

“It was in November (of 1532), bitterly cold,” wrote Cabeza de Vaca, “and we in such a state that every bone could easily be counted, and we looked like death itself. At sunset, the Indians came… Upon seeing the disaster we had suffered, our misery and distress, the Indians sat down with us and all began to weep out of compassion for our misfortune.”

An extraordinarily cold and harsh winter, coupled with a lack of food, reduced the number of would-be colonizers to 15 souls.

“What had begun as a guest-host relationship between the natives and the Spaniards,” writes Reséndez, “eventually degenerated into a relationship between masters and slaves.”

Without their guns, armor and horses, the conquistadors posed no threat to the local people. On the contrary, the Spaniards proved incapable of hunting with bows, fishing or trapping, so they were given women’s work to do: digging for roots, carrying firewood and fetching water.

The situation of the castaways degenerated even further when it was discovered that five of them — who had not taken up residence with the Indians — had avoided starvation by resorting to cannibalism. By the end, quips Cabeza de Vaca, “Only one remained because he was alone and had no one to eat him.”

Their Indigenous captors were greatly shocked and wanted to kill the Spaniards, but Cabeza de Vaca’s owner calmed them down. From then on, the castaways were forced to do brutally hard work and to suffer ignominy and derision on the part of all the tribe members, including the children.

These Indigenous people, the Capoques and Hans, says Reséndez, were not what we are accustomed to call slavers:

“They did not actively procure and exploit slave labor. They certainly possessed slaves, which were a byproduct of their continuous warfare with neighboring groups… However, this system was a far cry from that employed by more centralized and hierarchical societies like Portugal and Spain.”

Eventually, the group of Spaniards dwindled to four and they were taken to the mainland by their owners to help pick pecans and prickly pears in season.

In 1534, not only were they able to slip away from their captors, they also discovered a modus operandi that would assure them safe passage through whatever strange lands lay before them: they became medicine men.

Surprisingly, it was not the castaways who first suggested that they possessed the power to cure the sick but the Indigenous inhabitants. This began back on Galveston Island. Says Cabeza de Vaca, half joking: “On that island, they tried to make us physicians without examining us or asking us for our titles.”

The Indigenous people had demanded that the castaways cure the sick by blowing on the afflicted. The Spaniards took things lightly at first.

“We laughed at this and said that it was a mockery and that we did not know how to cure.”

But, says Reséndez, their hosts were serious. They stopped feeding the outsiders until they did as they were told, and one of them patiently explained to the uncomprehending foreigners that, in the words of Cabeza de Vaca, “even the stones and other things that exist in the wild possess power, and that he used a hot stone rubbed on the abdomen to heal and remove pain, and that we (the survivors), who were humans, had even more virtue and power.”

It was fortunate indeed that in October 1534, the four escapees fell in with a small nomadic band of Indigenous people known as the Avavares, who had heard of the castaways’ reputation as shamans and treated them with respect. They gave them lodging with their own medicine men.

Their new careers began on their first night among, when several Avavares suffering from head pains showed up looking for a cure from the foreigners.

One of Cabeza de Vaca’s group, Alonso de Castillo, made the sign of the cross over these men and begged God to give them health. According to Cabeza de Vaca, “The Indians said that all the sickness had left them. And they went to their houses and brought many prickly pears and a piece of venison, which at the time we didn’t recognize.”

The four men’s newfound position was a far cry from their past lives as captives. Avavares who were treated by a medicine man were accustomed to giving everything that they owned to him and even sought additional gifts from their relatives. Over the course of a few days with the Avavares, the four outsiders received so many pieces of venison that they didn’t know what to do with all the meat.

After that, the reputation of the foreign medicine men preceded them across the continent and south to Sinaloa, where in 1536 the unexpected appearance of “bearded Indians speaking perfect Spanish” dumbfounded their countrymen.

By the time Cabeza de Vaca’s group reached Mexico City, the four remaining castaways had walked over 3,800 km.

Their story is well worth a read. And then pack the book away for that future trip to a desert island.

- Andres Resendez’s book, “A Land So Strange,” published by Hachette Press, can be found on in print and e-book on Amazon. Prefer to watch the movie? It’s harder to find but it’s available for free to watch online if you’re in Mexico on the FilmInLatino website.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.

Source: Mexico News Daily