IN FOCUS: Can Southeast Asia fix its notorious traffic jams?

In the Thai capital, resident Rossana Nitikanchana devotes up to two hours in total every day driving her children to and from school. Once, when heavy rain combined with schools reopening after COVID-19 lockdowns, she took a whopping four hours to complete the mere 12km journey back to her house in the Sukhumvit district.

The 38-year-old still insists that she likes driving for the convenience, but rues the hours lost in Bangkok’s bottlenecks. “I normally like working out but I don’t get to do it because I have to waste time in traffic jams,” she said. “I don’t really have time left to do other things.”

HAVE CAR, WILL CONGEST

A preference for one’s own set of wheels is clear across the regional cities, where private vehicle ownership increasingly trumps residency numbers.

That’s 11.7 million machines to about 11 million people in Bangkok and its surrounding urban region; and 9.85 million versus 9 million in the Klang Valley area covering Kuala Lumpur and adjacent areas. Jakarta and its wider metropolitan areas are occupied by 20.7 million vehicles to 13.5 million people.

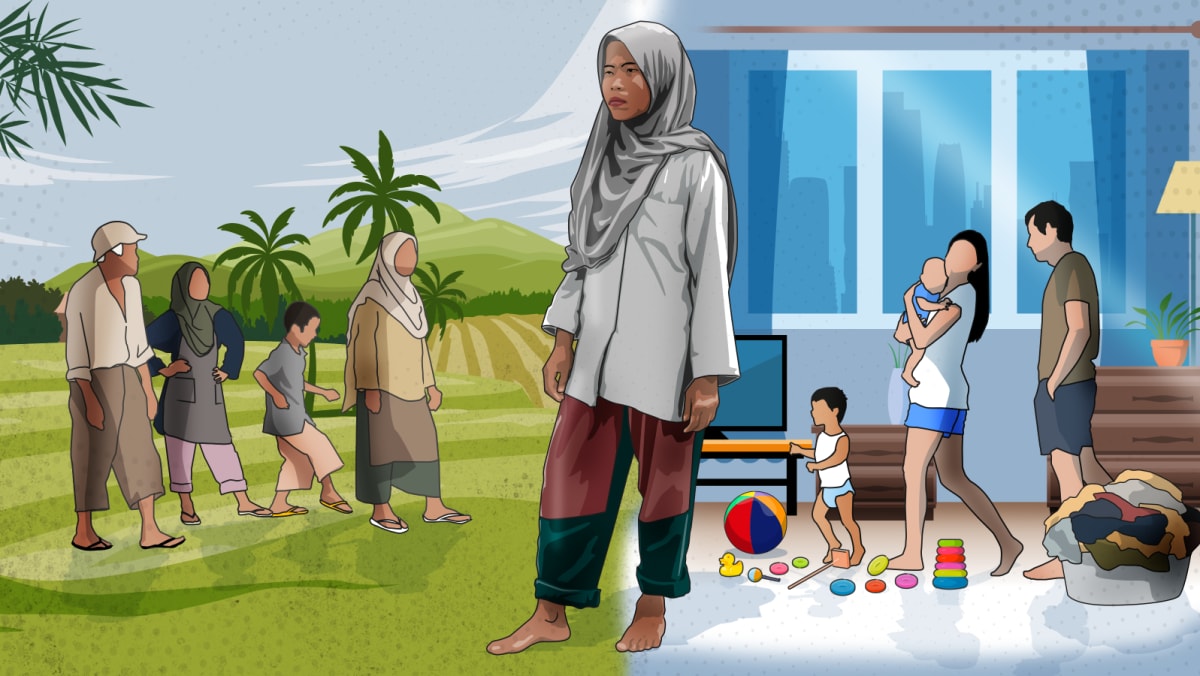

“Even those who don’t own a home have either a car or a motorcycle,” said Mr Djoko Setijowarno of the Indonesia Transportation Society network of experts.

They are helped by relatively low prices and little or no restrictions placed on owning and using a private vehicle, whether new or handed down. In fact, there are often fuel or purchase subsidies for private vehicles, said Associate Professor Theseira from the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

An abundance of cheap parking space also encourages more vehicles, more driving and ergo, more congested roads.

Parking in Bangkok is easy and unregulated with “no control whatsoever”, said Dr Sumet Ongkittikul of the Thailand Development Research Institute, adding that 80 to 90 per cent of Bangkok’s traffic congestion is due to parking space.

“We facilitate car users so much that it has become … the most convenient option, both in terms of time and cost,” said the transport research director at the think-tank.

What experts dub “traffic discipline” is another factor. This refers to stopping and parking vehicles where one isn’t supposed to; taxis dwelling in left lanes to wait for customers – and inadequate enforcement against such behaviour.

This brings us also to road capacity, in cities where thoroughfares range from six-lane tollways to small back alleys barely wide enough to fit a single car. “There is often a failure to redesign the road network to accommodate higher volumes of traffic,” said Assoc Prof Theseira.

Yet building more roads and expressways is hardly the answer – and as several have argued, only compounds the problem.

“Some highways that were once relieving congestion 10 years ago are now themselves congested,” said civil engineering professor Ahmad Farhan Sadullah from Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), citing the example of the Maju Expressway or MEX connecting Kuala Lumpur to the administrative capital Putrajaya.

Source: CNA