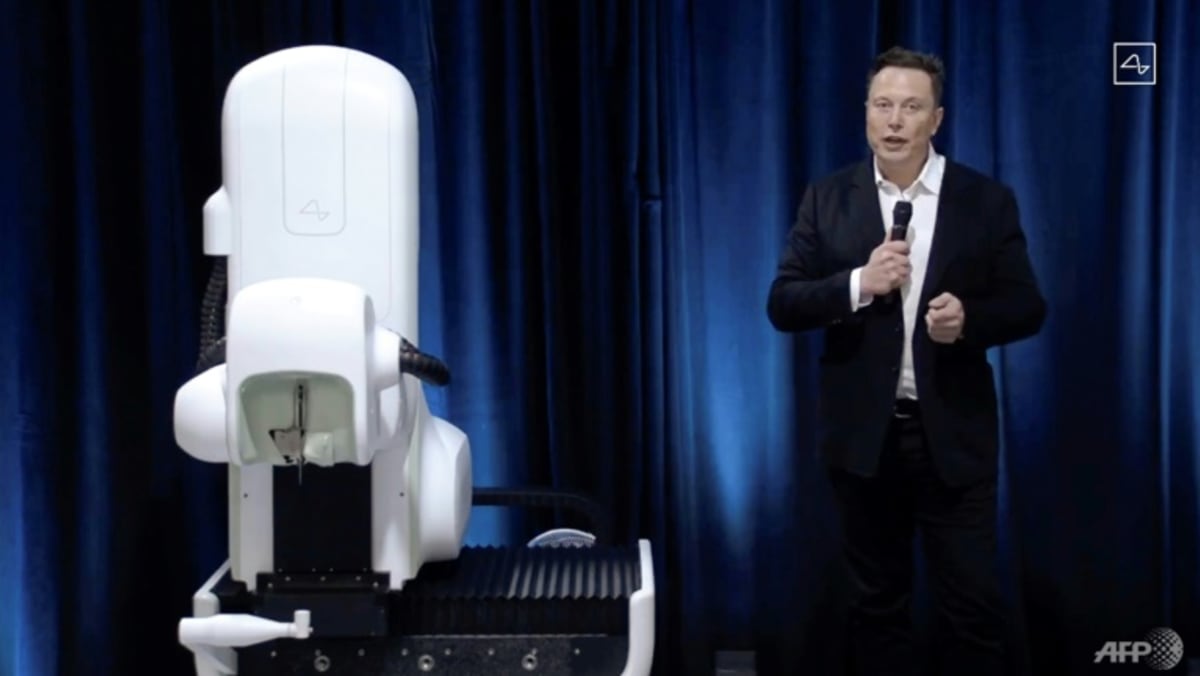

Commentary: Would you let Elon Musk implant a device in your brain?

INSIDIOUS INTRUSION

Another vision for this technology is that the owners of computers will want to “rent out” the powers of human brains, much the way companies rent out space today in the cloud. Software programs are not good at some skills, such as identifying unacceptable speech or images. In this scenario, the connected brains come largely from low-wage labourers, just as both social media companies and OpenAI have used low-wage labour in Kenya to grade the quality of output or to help make content decisions.

Those investments may be good for raising the wages of those people. Many observers may object, however, that a new and more insidious class distinction will have been created – between those who have to hook up to machines to make a living, and those who do not.

Might there be scenarios where higher-wage workers wish to be hooked up to the machine? Wouldn’t it be helpful for a spy or a corporate negotiator to receive computer intelligence in real time while making decisions? Would professional sports allow such brain-computer interfaces? They might be useful in telling a baseball player when to swing and when not to.

The more I ponder these options, the more sceptical I become about large-scale uses of brain-computer interface for the non-disabled. Artificial intelligence has been progressing at an amazing pace, and it doesn’t require any intrusion into our bodies, much less our brains. There are always earplugs and some future version of Google Glass.

The main advantage of the direct brain-computer interface seems to be speed. But extreme speed is important in only a limited class of circumstances, many of them competitions and zero-sum endeavors, such as sports and games.

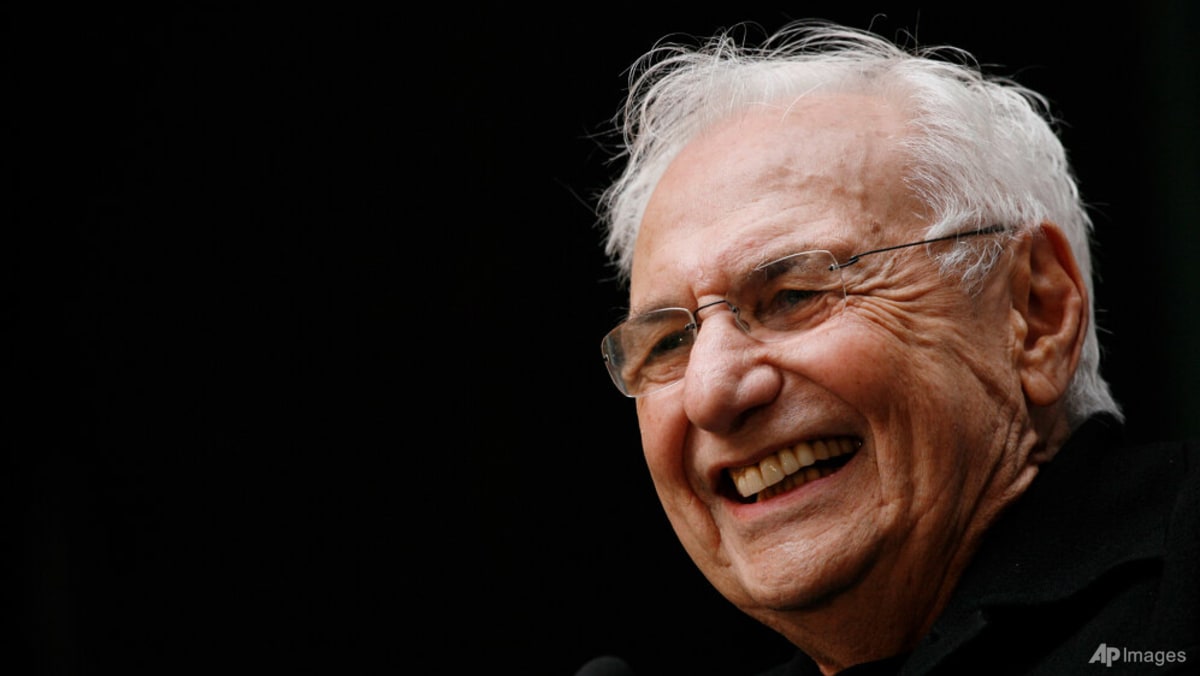

Of course, companies such as Neuralink may prove me wrong. But for the moment I am keeping my bets on artificial intelligence and large language models, which sit a comfortable few inches away from me as I write this.

Source: CNA