Is anti-French sentiment prevailing in Francophone Africa?

Anti-French rhetoric in French-speaking Africa has spread beyond the educated urban elite, and the phenomenon could “take root for a long time”, says Alain Antil, a researcher at the French Institute of International Relations (Ifri), in an interview.

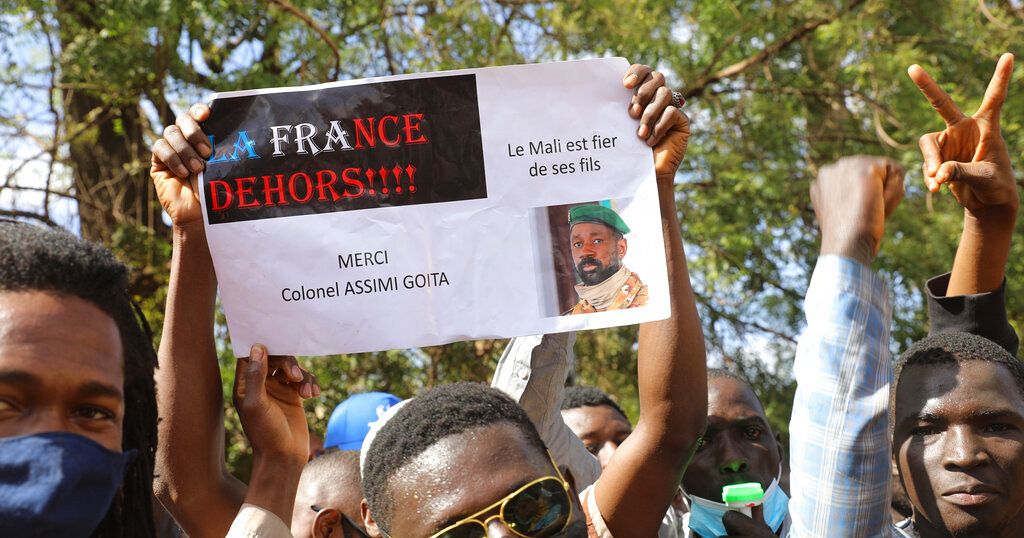

In recent years, criticism of France’s policies has been accompanied by violent demonstrations against French companies such as Total and against diplomatic representations in Chad, Mali and, more recently, Burkina Faso.

The depth of the phenomenon is “nothing like what we saw in previous decades”, points out Alain Antil, who heads Ifri’s Sub-Saharan Africa Centre and who on Wednesday, with his colleague Thierry Vircoulon, is publishing a study devoted to “Themes, actors and functions of anti-French discourse in French-speaking Africa”.

We are a long way from the days “when highly articulate criticism (…) was confined to leading circles of intellectuals and sometimes, during serious political crises, spilled out onto the streets,” he says.

It is striking to note that critics no longer even try to demonstrate untruths: “we no longer even need to prove that France supports jihadism. We just say so,” he observes.

For the researcher, the intensification of anti-French sentiment can be explained by “disappointing economic and political trajectories” in countries where the population had once pinned their hopes on economic progress and democracy.

Denial

Faced with the failure of their own policies, the leaders of these countries resort to “scapegoating techniques”: “France is ultimately responsible for the non-development of these countries and the corruption of their elites”, explains Alain Antil, “It is always an argument that comes to explain, and ultimately absolve, the responsibility of these elites”.

At the same time, this anti-French rhetoric has been able to flourish because French leaders have been slow to react.

Until very recently, the French authorities “were in a kind of denial”, seeing it simply as a correlation with crises, “outbreaks of hives” or manipulation by the Russians, explains the researcher.

The study does show “a link between this Russian propaganda war and certain segments of African social networks”.

It is undeniable that social networks have massively circulated false information, such as videos or photos showing French soldiers “supposedly” stealing gold or “consorting with jihadists”, stresses Alain Antil.

But the expert warns against the temptation to explain everything in terms of Russian propaganda.

“Obviously, the Russians are playing their part, having an impact and funding anti-French campaigns,” he says.

However, he warns that it would be a mistake to think that “explaining to Africans that they are being manipulated by the Russians will put an end to it”.

Far from abating, this rhetoric will take root “for a long time in the politics and public opinion of these countries,” he adds, citing three factors fuelling anti-French sentiment: the military presence, the development aid policy and the currency.

While the number of French troops has fallen drastically from 30,000 in the early 1960s to around 6,100 today, “interventionism has not diminished”, notes the researcher.

On an equal footing

As far as the CFA franc is concerned, whatever the reforms and the distancing from France, the name CFA franc alone remains “a symbol”, even though the former colony has adopted the euro.

Although present, anti-colonial discourse is “not central” to the spread of anti-French sentiment, observed the researchers, who reviewed social networks and newspapers.

“It is rather the post-colonial period” that is to blame.

The researchers did not make any recommendations, but Alain Antil, interviewed by AFP, noted the need to be sensitive to the opinions of these countries.

“On the French side, there are often awkwardness in the way we address our interlocutors,” he explains. “Form counts for a lot” and “we don’t measure that enough,” he says, recalling the criticism levelled at President Emmanuel Macron during his recent official trip to Africa.

“African public opinion is extraordinarily sensitive and understandably so to the fact that they are being treated as equals and not as someone who lectures or ironies”, he concludes.

Source: Africanews

![New era of sovereignty in Mali’s gold sector [Business Africa] New era of sovereignty in Mali’s gold sector [Business Africa]](https://static.euronews.com/articles/stories/08/77/73/76/1024x538_cmsv2_04bbdd41-5576-5c9e-9bd3-f09c391cff64-8777376.jpg)