Documenting “many Mexicos”: Meet photographer Bob Schalkwijk

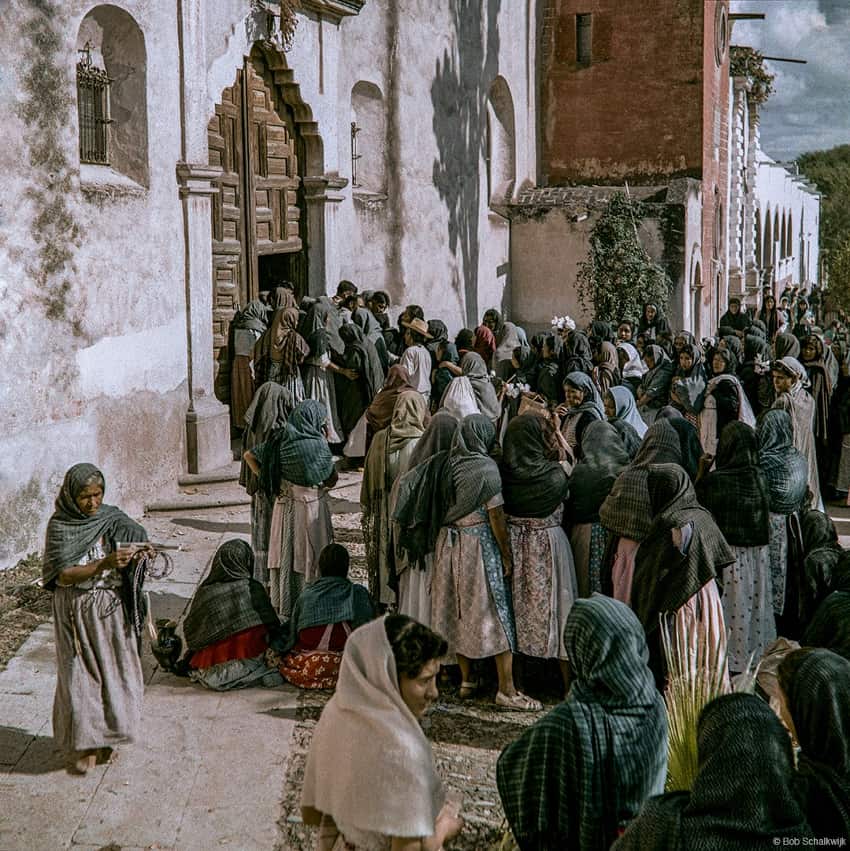

Frida Kahlo’s diary, the aftermath of the destructive 1985 Mexico City earthquake, the Indigenous Tarahumara people and the 1968 Summer Olympics.

They are just a few of the vast array of subjects photographed by Dutch photographer Bob Schalkwijk during a long and illustrious career in Mexico.

Schalkwijk – who was born in Rotterdam in 1933 – has tirelessly documented Mexican life for over six decades, taking countless uplifting, evocative, poignant and thought-provoking photos.

His impressive archive of personal and commercial work also includes photographs of architecture, art, fashion, food and landscapes, to name just a handful of the broad categories he has focused on.

The long-term Mexico City resident is currently exhibiting a selection of his photographs from the past 65 years at the Centro de la Imagen museum in the historic center of the capital. In addition, part of his “Paisajes de Agua” exhibition of waterscapes is on display at the Museo de la Ciudad (City Museum) in Cuernavaca.

At the age of 90, Schalkwijk continues to travel and photograph in Mexico, but found the time to respond to the following questions I put to him by email.

Peter Davies:

Hi Bob, thanks for speaking to Mexico News Daily. You’ve lived in Mexico for over 60 years. What originally brought you here?

Bob Schalkwijk:

At the beginning of 1958, after having completed some courses in Baytown, Texas, on oil pipelines, I applied to Stanford University to study petroleum engineering. I passed the exam, but I had to wait months to start classes. I thought that with my knowledge of oil pipelines, I could find a job in the Trans Mountain Pipeline in Canada.

But I didn’t get a job, and in February 1958, while I was having coffee at the Calgary airport, I read in Esquire magazine that in Ajijic, Jalisco, a couple could live and eat very well for about $150 a month.

With an occasional friend, at the beginning of winter, the idea of living on the shore of a lake, with food and drinks was fabulous. We didn’t think twice and aboard my vocho (Volkswagen Beetle) we drove from Calgary, Canada to Ajijic, in Mexico.

Once we ate and drank very well, we got bored with the atmosphere of the people who lived in Ajijic – retired Americans, over 50 years old and at that time I was still 24 years old. Thinking of taking advantage of our stay in Mexico, we headed to the capital, with the idea of learning Spanish, and that’s how it all began.

PD:

What inspired you to become, and how did you go about becoming, a professional photographer?

BS:

Photography has been with me since I was little. I knew about the passion that my paternal grandfather had for photography. He was not a professional photographer, nor did I know him, but his photographs and his photographic adventures excited me.

I loved photographing since I was 14 years old, when my father gave me a Kodak Brownie 127. That was my first camera. My parents also supported me in having a dark room and I would spend hours developing and printing my photos.

I was a rebellious student, but the Agfacolor book written in German by Dr. Heinz Berger, explaining the technique of color photography, and which I presented in my German final exams, saved me from being a bad student and increased my love for photography.

Over the years I had better cameras and at the age of 19 I sold some portraits of Louis Armstrong that I took at a concert at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. That made me very happy, but I knew that I couldn’t make a living from photography in the Netherlands. That’s why I went to Texas to study oil pipelines.

Once in Mexico City, after a visit to Puerto México, then a small town in Hidalgo – which I called “the Otomí Country” – things changed. Fred Mulders, a Dutchman who lived in Mexico, who loved being here, was the one who took me to Hidalgo, and by pure chance, while I was studying Spanish, I was fortunate to meet people who made a living from art and photography. Fred introduced me to Walter Reuter, a German-born photographer and film director, who encouraged me to study film and to collaborate with him. So even though I returned to Stanford, my interest in petroleum engineering waned.

In college I took film classes, started taking pictures and went to a San Francisco newspaper to promote the pictures I took in the Mezquital Valley [in Hidalgo]. I didn’t get anywhere with the newspaper, but I was brave enough to drop out of Stanford University and set up as a photographer in Mexico City.

PD:

You’ve traveled extensively in Mexico during your long career as a photographer. Can you tell us a little bit about your travels through the country and the changes you’ve seen over the decades?

BS:

In those early years in Mexico I had a used VW, which my father had given me, and which had 128,000 kilometers on it. From 1958 to 1960, the year I sold it, I put another 100,000 kilometers on it. I have always preferred doing photographic work that allows me to travel – to be able to photograph what interests me.

In 1959 I went to Acapulco, Tepoztlán, and Oaxaca, and the following year I ventured to Chiapas alone. I was inspired by photographers like Pierre Verger, Robert Frank and Werner Bischof, who traveled to South America and photographed in a very emotional and caring way, recording the most human aspects and the simplicity of life in the communities.

Mexico, which for me is made up of “many Mexicos”, fascinated me and continues to fascinate me.

It is true that things have changed, not always for the better, but the people of Indigenous communities or small towns continue to be essentially simple.

PD:

You were in Mexico City when the devastating 1985 earthquake occurred and took numerous impactful photos showing both the destruction and the human side of the disaster. What do you recall of that difficult time?

BS:

What surprised me the most about the earthquake was the solidarity that was shown at the moment. Everyone began to help, with the resources that each person had and without anyone organizing them.

I lost my best photographs from the first day – that is a sad story that I inevitably remember. That September 19, after the earthquake and after I was sure everyone in our family was safe, my assistant Javier Tinoco and I, on my children’s bicycles, left Coyoacán, where I live and where my studio is, for the historic center.

The devastation was terrible. We worked all day until there was no light anymore. During those years I was a correspondent for the Black Star agency in New York. I knew that my photographs would interest them.

Very tired, without having eaten, we had a bite at a local restaurant and returned to the studio to develop the rolls of black and white film and color slides, both of which I worked with from the beginning of my career as a photographer.

Almost without sleep, the next morning, I went to the courier service where I used to send my work, but it was closed. Without thinking too much about it, I went to the airport, looking for someone who could take my photos to New York. I found a man, most likely an American, and asked him if he could deliver my photographs. I even gave him some dollars so that he could take a taxi and leave them at the agency. My photographs, the ones we had selected – the best ones – never arrived.

During the following days I continued photographing the disaster. A major bank hired me to photograph the damage to their branches. About a month later I was asked to photograph the demolition of the Multifamiliar Juárez, a large apartment complex, in the Roma neighborhood. With those photographs a book was made in homage to [Guatemalan artist] Carlos Mérida, who made fantastic designs to be integrated into the architecture.

PD:

Mexico City has been your home for many years and, seemingly, a muse for your work as a photographer. What does the capital mean to you and how has it inspired and/or influenced your photography?

BS:

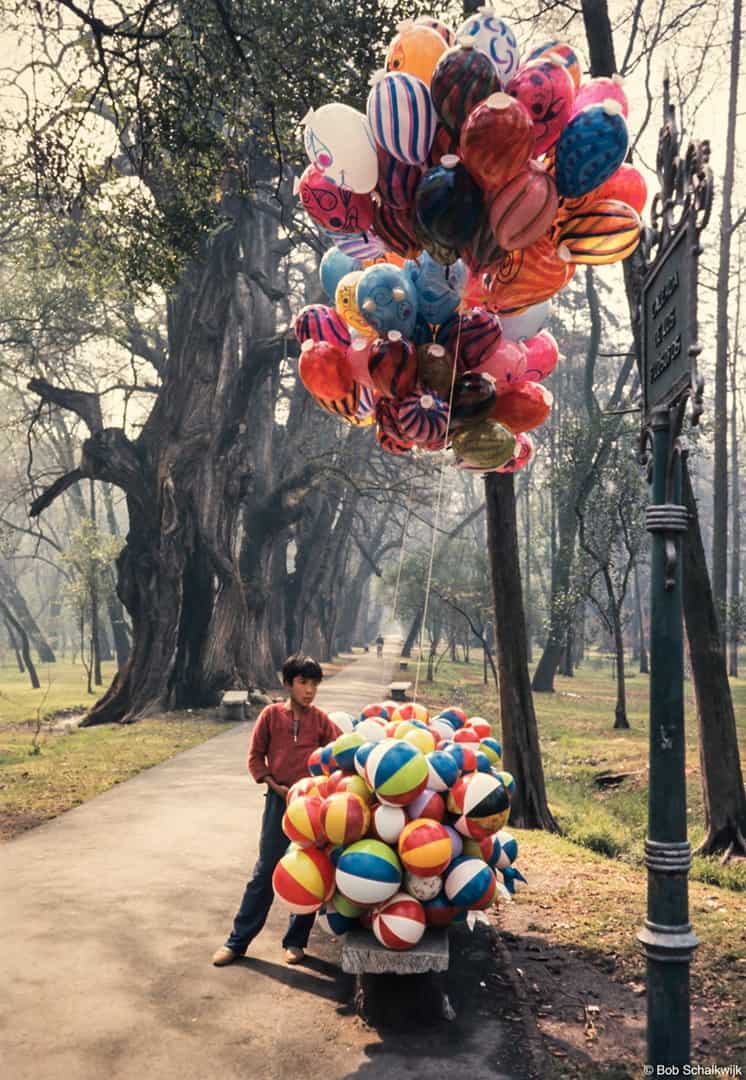

Since I settled in Mexico City, I began to go for walks accompanied by my camera to observe and photograph the situations that I saw. A place that I loved and that I still like is the Bosque de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Park), and I often walked along Avenida Reforma, which is fantastic, with its tree-lined sides surrounded by avant-garde buildings.

I also love areas like San Ángel, where I came to live at the beginning, and Coyoacán.

In Mexico City everything happens, there is a very special way of being from the capital, being chilango, and it is perhaps the historic center – the space in the center of the capital – that is most attractive in Mexico City.

PD:

You have taken photos in dozens of countries around the world. Can you tell us about some of your experiences abroad?

BS:

Men and women are essentially the same, our cultures make us different, we dress in different ways, we eat different dishes, of course there are economic and political differences, often unfortunate, but on average, in people there is a vital and human essence that makes us equal.

I grew up during World War II. I could have died of anemia from not getting enough food and for that very reason I appreciate the good things in life.

When I travel, I like to photograph the differences, but also the similarities [between people around the world]: the day-to-day work, the play of girls and boys, young people who fall in love, old people with their wrinkled faces.

I like to observe, to stop to understand what is happening. And what I have seen is that we could be better people if we looked at others.

Find more of Bob’s photography on his website, on Facebook and on Instagram.

This interview is the second in a series called “The Saturday Six”: six-question interviews published in Saturday editions of Mexico News Daily. Read the first interview in the series here.

Source: Mexico News Daily