Adapting to change: pastoral farming in a warming climate

Farmers in Kenya are increasingly adopting camels as a drought-resistant substitute for the cattle they have traditionally raised.

In rural Kenya, it’s typical to see pastoral farmers herding their cattle.

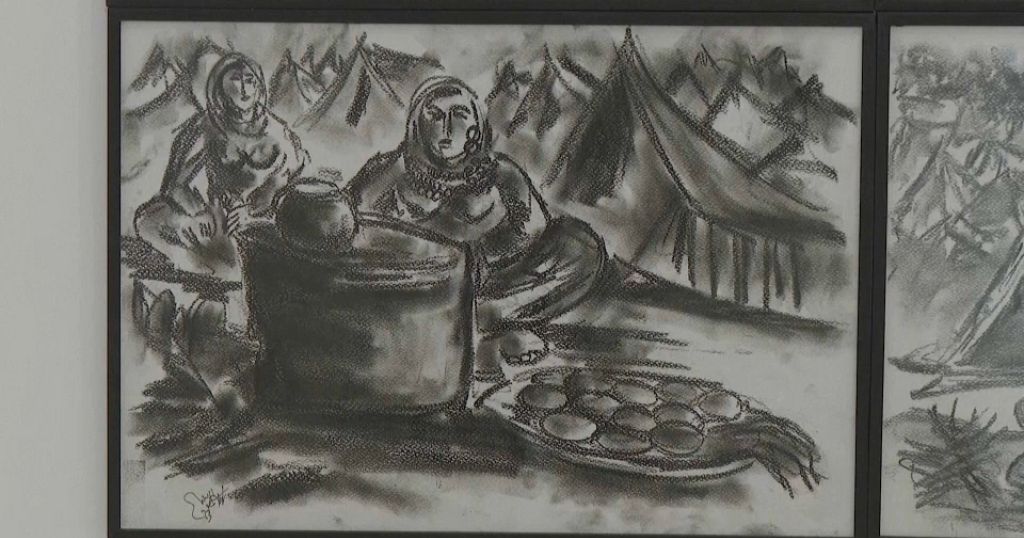

For the Borana and Samburu communities in the northern region, cattle represent social status particularly in cultural rituals as well as weddings and are vital for providing milk and meat to families, but climate change is disrupting this traditional way of life.

In Lekiji village, located 252 kilometers from the capital, Abudlahi Mohamud a camel herder tends to his camels.

The 65-year-old, who is a father of 15, suffered a significant loss during the 2022 drought, as nearly all of his 30 cattle perished. “I had a herd of 30 cattle before the drought, but when it struck, only one survived,” he explains.

Heartbroken by the tragedy, Mohamud chose to invest his savings in 20 camels, believing it to be a wise decision.

In 2022, climate change and droughts led to the death of approximately 2.6 million cattle, but camels prove to be more resilient and better suited to withstand climate challenges.

Mohamud, states that “Rearing cattle is difficult due to inadequate pasture. In contrast, camels are easier to rear as they primarily feed on shrubs and can survive in harsher conditions. When the pasture dries out, all the cattle die.”

A report from the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) indicates that the extended drought of 2022 resulted in the loss of approximately 2.6 million cattle, with damages estimated at 226 billion Kenya Shillings (1,753,618,750 United States Dollars).

The rising population has intensified competition for grazing areas and water resources.

Mohamud states that a small camel is priced at approximately $600 USD, while cows can be purchased for about $150 USD.

According to the Kenya Agricultural Livestock Research Organization (KALRO), more than 70 percent of Kenya’s land is made up of rangelands.

However, camels may offer a potential solution.

While camels may not be the first animals that come to mind when thinking of Kenya, farmers in the area are increasingly adopting them as a drought-resistant option compared to cattle.

Although camels make up only six percent of Kenya’s herbivore population, totalling 960,000, they offer distinct benefits over cattle.

The Somali community in Northern Kenya was the pioneer in camel herding, a practice that eventually extended to other tribes like the Samburu, Turkana, Pokot, and Maasai.

By incorporating camels into their traditional herding methods, these pastoralists can mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change and maintain food security.

Nearby, 26-year-old Musalia Piti tends to his father’s herd of 60 camels.

After losing 50 cows in a drought, the family opted to invest in camels, allowing them to sell some when they require cattle for cultural ceremonies.

Camels require less water and can graze on a broader range of plants.

Their elongated bodies help minimize the surface area exposed to sunlight, allowing them to better cope with heat stress.

The shift from cows to camels represents a major adaptation to growing climate threats and is intended to enhance long-term climate resilience.

The goal is to foster long-term sustainable climate resilience, but this transition has also affected cultural traditions.

For the Samburu, cattle symbolize status and serve as dowry in marriages.

Lesian Ole Sempere, a 59-year-old elder from the Samburu community, discusses the significance of cattle in marriage ceremonies: “It’s essential to do everything possible to acquire cattle for weddings, even if our herds are smaller now. At first, you might not be required to provide cattle for the dowry, but giving a cow as a gift to the parents is advisable. This act helps persuade them to recognize their daughter as your legitimate wife.”

Cattle possess certain advantages over camels, and raising a caravan of camels can take more time in the short run.

Nevertheless, the Samburu remain committed to their cultural practices and reject the notion that these traditions will vanish due to the shift from cows to camels.

By incorporating camels into their herds, which they sell when they need cattle, the Samburu demonstrate their dedication to maintaining their cultural identity despite evolving conditions.

Calvince Okoth, a Veterinarian and Livestock Manager at Mpala Research Centre, notes that the recent droughts have diminished available pastures in the community.

One effective strategy for managing these pastures is implementing rotational grazing, which involves designating specific paddocks for use during the dry season.

However, a significant challenge arises from the communal ownership of the land, allowing unrestricted access for anyone at any time.

There are also issues with encroachment, as individuals can also access these pastures.

Climate change is leading to unpredictable weather patterns in the Horn of Africa, prompting the adoption of new agricultural methods in the area.

In response to droughts that are decimating their cattle, some Maasai farmers have turned to fish farming.

Additionally, camels offer a viable alternative that may help preserve traditional pastoralist lifestyles in the 21st Century.

Whether or not Camels will be fully embraced by these communities it is a matter of wait and see.

Source: Africanews