In search of authenticity amid the gentrification of Mexico

12 years ago, when I was living in Querétaro, my sister came to visit, and we decided to take a day trip to San Miguel de Allende. It seemed like the perfect, authentic destination: San Miguel’s mild temperatures and beautiful mountain surroundings, combined with a well-maintained small town charm, make it an ideal place. The artisan market is also lovely, and the city has an old reputation as an artistic hub. It’s also now seen as as a hotspot for gentrification in Mexico.

As we wandered the zócalo, it seemed we were passing more “paisanos” than Mexicans. San Miguel was and still is a major destination for U.S. and Canadian retirees looking to settle down in Mexico. Mostly older and clearly happy to be there, they dotted the benches, chatting in a mix of English and halting Spanish.

“Oh,” my sister said. “I didn’t know you would be here.”

What is the “real” Mexico anyway?

On its surface, it seems like an uncomplicated question: the real Mexico is the society in which“real” Mexicans live.

Most foreigners and many Mexicans would say that obvious tourist destinations like Los Cabos or Cancún aren’t “the real Mexico.” This is something that always makes me wonder if Mexican locals would beg to differ. Still, that’s the general consensus.

But what of places like Oaxaca city, which has exploded in popularity over the past decade? What about San Miguel de Allende? Does the dynamic of outsiders trying to adapt to local customs — as opposed to treating it like a grown-up playground or a place to be improved — make a difference?

Even the term “real Mexicans” seems to be up for debate at times, particularly among Mexicans. One of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s favorite pastimes, for example, seems to be invalidating the “fifis” — his word for upper class Mexicans. Others have named this class Whitexicans. They may have an outsized presence on social media and in the popular imagination, but they actually make up a quite small portion of the population.

While some might argue that they grow up in an isolated bubble, the suggestion that they’re not “real” is silly.

And yet. what if a great many of them up and move to downtown San Cristobal, or Oaxaca? Would they not change a place as much as foreigners, and possibly do it on purpose? Foreigners are typically the ones credited – or blamed – for such changes, but I have my doubts.

So the question remains: Is what people consider the “real” Mexico still the real Mexico once a certain noticeable threshold of new arrivals — from foreign countries or other parts of Mexico — has been passed? And does it matter where those new arrivals are from? During the years I was there, the main complaint among Querétaro natives was the influx of chilangos.

Querétaro, they said, wasn’t what it used to be. Only certain enclaves were now the “real” Querétaro. The new arrivals from Mexico City had fundamentally changed the city, stuffing it with traffic and looser morals than the typically conservative queretanos found appropriate.

The places, they are a-changin’

This is the nature of things. Wonderful destinations are discovered, and then become popular. More people show up. And then more people. And then even more people, sometimes until the place barely resembles what made it attractive in the first place.

Those who arrived first — and those who lived there before it was “discovered” — often lament the change. It’s more complicated, of course, than the simple platitude “Everything was better before.” A larger population brings pros — more services — and cons — more traffic — and, like everything, is a mixed bag.

As the saying goes, change is the only constant.

Unfortunately, most humans do not like change. “It’s not what it used to be,” we say as we shake our heads.

Move over, will ya?

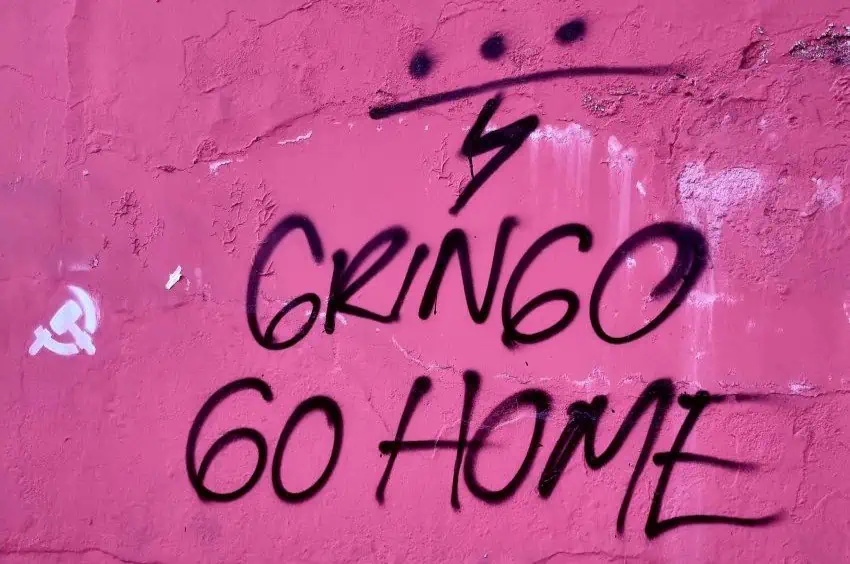

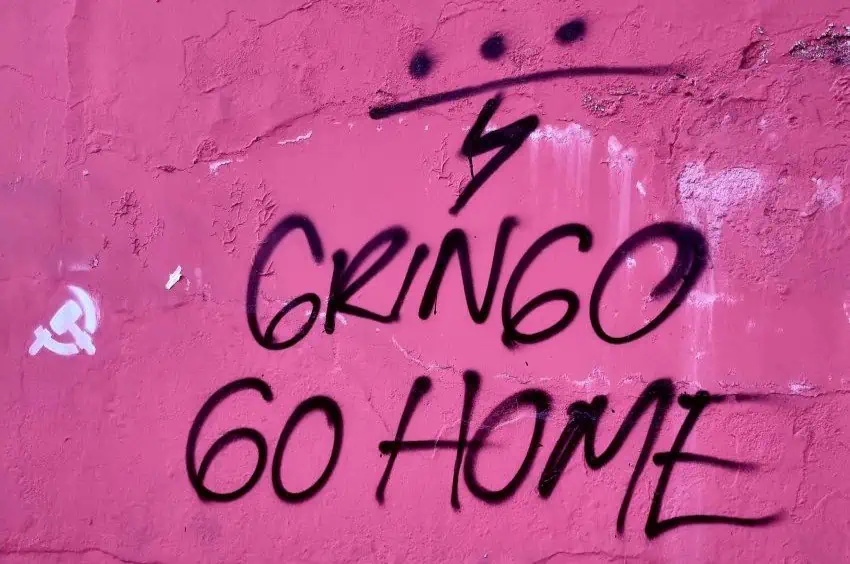

The worldwide travel theme of this past summer seems to have been this: everything is too crowded, changing things too fast. I read about it in the protests among European city dwellers, their local hangouts choked with tourists. I’ve seen it on a prominent storefront window in my city: “No to gentrification!” I’ve seen the posts by anxious Mexicans, sure that we foreigners are responsible for higher housing costs and too-fast change in their communities on Facebook: “Please don’t come here.”

Meanwhile, sleek marketing materials continue to entice us with pictures of a woman in a sun hat on the beach sipping a piña colada, not a soul in sight. Actually though, there are a lot of souls. Everywhere. They’re causing traffic. They’re in line for the bathroom — only two stalls out of five are working, of course. They’re taking up all the best spots on the beach.

This isn’t only about tourism, of course. There are lots and lots of people in this world. And there are plenty of communities who feel they’re running out of enough space and resources to go around when their population quickly jumps in size.

Especially when there are limited resources in a tourist economy, ask yourself if resources like water will end up going to the hotel resorts or to the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Exactly.

Do I have a solution? Absolutely not. Would I like to write an article about how great the city where I live is for expats, as my editor requests? Absolutely not.

Like the rest of us, I’m a hypocrite in so many ways, one of them being that I want to be welcomed to the pristine, uncrowded places I go. And then I want the door shut tight behind me, which is both selfish and unfair.

I’m not a crowd, you’re the crowd. Give me some space!

Such is our nature. Perhaps in 20 years many of us will be talking about how “real” the Mexico of 2024 was: “Now, that was Mexico.”

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.

Source: Mexico News Daily