Have you heard about the wars of Yucatán independence?

In a country whose history is as hyper-focused around its largest city as Mexico is, it’s easy to overlook historical events that didn’t take place in or around the capital. But this is a big and diverse country, and major processes and events happened all across it. One such event is Yucatán’s independence from Mexico, something that has happened not once, but twice.

This period of Mexico’s history is of immense importance to the Maya peoples of the Yucatan Peninsula, as it marked the beginning of the Caste War, a Maya rebellion that spanned generations. Due to the amount of lives lost during the war, the Mexican government extended a formal apology to the Maya community in 2021, in a ceremony held at the community of Felipe Carrillo Puerto.

Yucatán and Mexico

The Spanish colony of New Spain was ruled from Mexico City and included the Captaincy-General of Yucatán, which covered the whole peninsula. Due to its great distance from Mexico City, Yucatán’s colonial history was marked by a degree of autonomy from the central colonial government, as well as important cultural differences, as the peninsula is the heartland of Mexico’s Maya peoples.

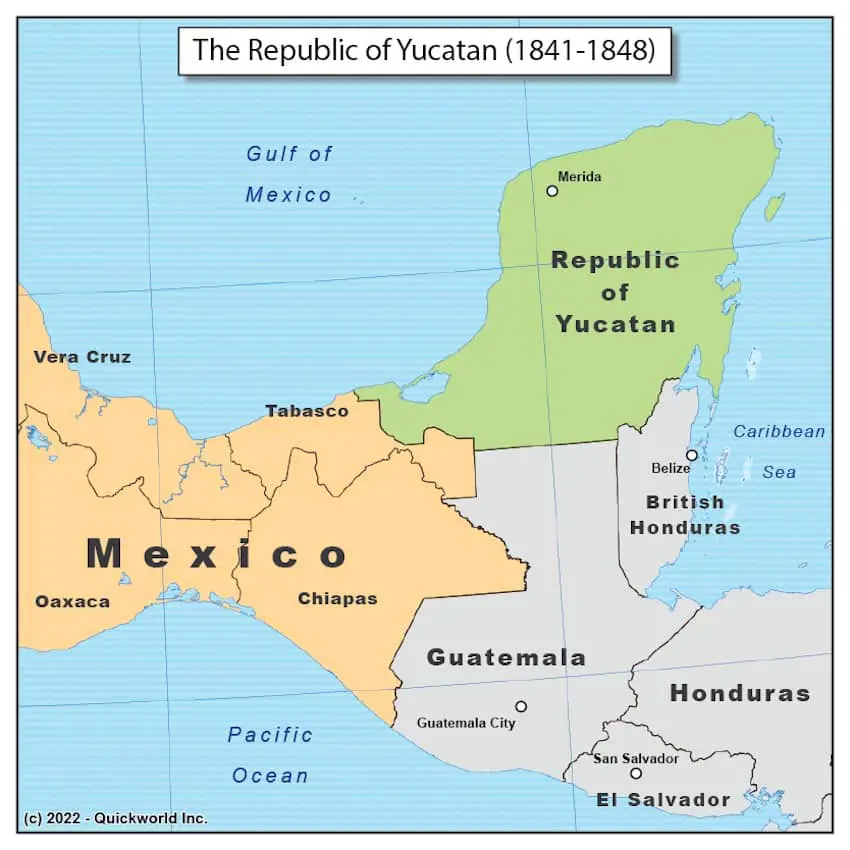

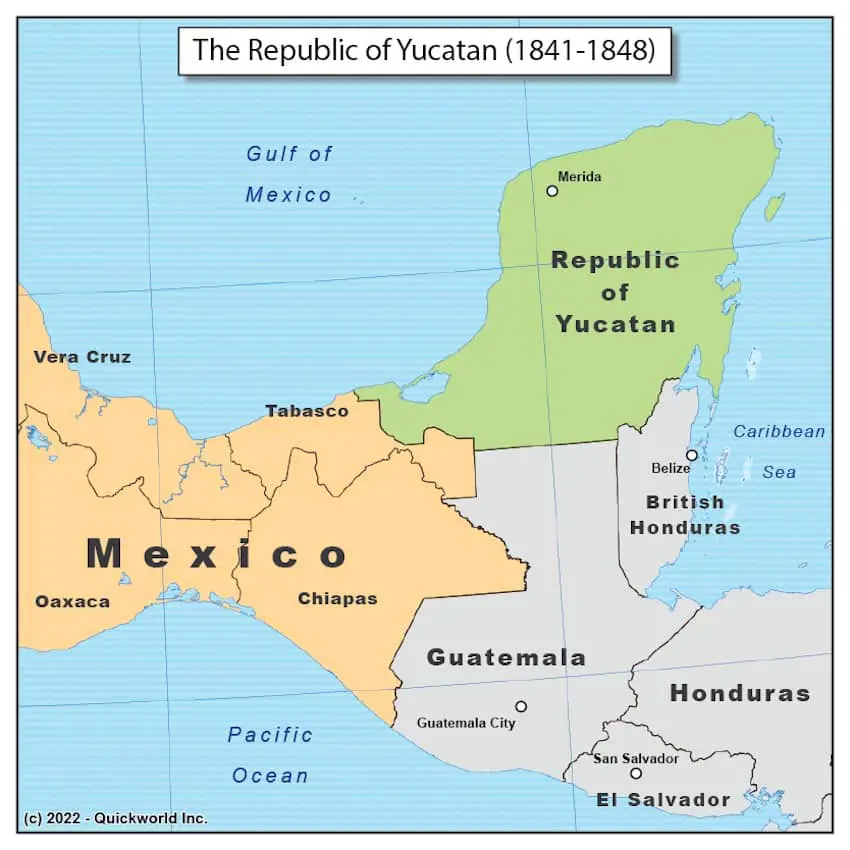

When independence movements broke out across the Spanish Americas beginning in 1809, Yucatán had its own movement that operated separately from the one in Central Mexico. The peninsula declared its independence from Spain in 1821. When Mexico declared its independence in the same year, it extended an invitation to Yucatán to become part of the Republic. Yucatán accepted under the condition that it would remain autonomous, and was admitted as the Federated Republic of Yucatán.

In 1836, the government of Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the federalist Constitution of 1824, which established the division of powers and granted autonomy to the states, to a centralist state in which the states became departments governed from Mexico City. This act kicked off a wave of rebellions across the country, with several states attempting to secede from Mexico — this was the context, for example, in which Texas took the opportunity to declare independence. Yucatán, unhappy with the new constitution, sought its independence too.

First attempt at Independence

In 1839, a separatist rebellion broke out in Yucatán, leading the state’s congress to end relations with Mexico until the federal regime was reinstated. On Oct. 1, 1841, the local Chamber of Deputies approved the Declaration of Independence of the Yucatan Peninsula, which stated that “the people of Yucatán, in full use of their sovereignty, declared themselves as a free and independent Republic within the Mexican nation.”

The national government rejected the separation and imposed sanctions on Yucatán. Santa Anna closed commercial ports between Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula and tried to prevent international commerce between the peninsula and Cuba, Jamaica and the English colonies.

Santa Anna also sent troops to invade Yucatán in 1842 and 1843. However, with the support of the Maya population, white and mestizo Yucatecans repelled the central government’s forces.

On Dec. 5, 1843, Santa Anna agreed to restore Yucatán’s autonomy if it was reincorporated into the Mexican Republic. Yucatán accepted the deal. Soon, however, the Mexican government declared the agreements null, and on New Year’s Day, 1846 Yucatán declared its independence once again.

Second attempt at Independence and the Caste War

The situation changed dramatically in 1846. In April, the United States invaded Mexico. The political turmoil the Mexican-American War unleashed in Mexico led to the readoption of the Constitution of 1824 in August. The government in Mérida, led by Miguel Barbachano, received the news happily and prepared to rejoin Mexico, but a rival government led by Santiago Méndez Ibarra had appeared in Campeche. The Campeche government, which also claimed to represent the Yucatecan people, wanted the peninsula to remain independent and neutral in the war.

It was in this context of crisis on the Yucatán Peninsula that the Caste War broke out. This social movement of the Maya population against white and mestizo Yucatecans would last over 50 years, and of all the Indigenous insurrections in Mexican history, the Caste War in the Yucatan Peninsula posed the greatest threat to the established order, coming within a hair’s breadth of victory.

The uprising began with the sentencing to death of Manuel Antonio Ay on July 25, 1847. The village chief of Chichimilá, Ay was accused of leading a conspiracy to overthrow white rule on the peninsula. With his execution, Ay became the first Maya martyr of the war.

With the weapons and training they received from the white Yucatecans during the 1839 rebellion, the conflict with Santa Anna and the struggle between the Campeche and Mérida governments, a group of Mayas led by chief Cecilio Chi and Jacinto Pat took up arms against them. One after the other, the wealthiest settlements south and east of Yucatán fell into the hands of the Maya until they conquered the city of Valladolid. After this, the entirety of the south and east of the Yucatán Peninsula was under Maya control for the first time in hundreds of years.

Desperate, then-President of Yucatán Santiago Méndez Ibarra, the leader of the Campeche faction that opposed reincorporation into Mexico, sought support from the United States and Spain. He explicitly offered dominion and sovereignty over the Republic of Yucatan to whichever country offered military assistance. A “Yucatan Bill” paving the way for annexation actually passed in the U.S. House of Representatives, but ultimately stalled.

Unable to put an end to the Maya rebellion, Méndez resigned as president of Yucatán and offered the position to Miguel Barbachano, who ultimately requested assistance from the government of Mexico against the Maya in exchange for the peninsula’s return to the republic. Yucatán rejoined Mexico in August 1848, and the resources they received from the federal government allowed the Yucatecans to push the Maya back to the southeast of the peninsula.

The Maya rebellion, however, was revitalized in the 1850s by a religious movement known as the Talking Cross. The Maya established a state in modern-day Quintana Roo known as Chan Santa Cruz, which signed international treaties and was recognized by the British as an independent nation. The Caste War saw some 250,000 people die. Many captured Maya were also sold into slavery in Cuba by the Yucatecans.

The war officially ended in 1901 after troops of the Mexican federal army occupied the capital of Chan Santa Cruz, now the city of Felipe Carrillo Puerto. Fighting continued for decades, however, and it was only in 1935 that the last Maya holdouts signed a peace treaty with Mexico.

Gabriela Solis is a Mexican lawyer turned full-time writer. She was born and raised in Guadalajara and covers business, culture, lifestyle and travel for Mexico News Daily. You can follow her lifestyle blog Dunas y Palmeras.

Source: Mexico News Daily