Where is the Pancho Villa skull, the head of Mexico’s revolutionary?

On Revolution Day, 1976, then-president Luis Echevarría honored one of the revolution’s greatest heroes, Francisco “Pancho” Villa, bringing his remains from the Panteón de Dolores in Parral, Chihuahua to rest forever in the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City.

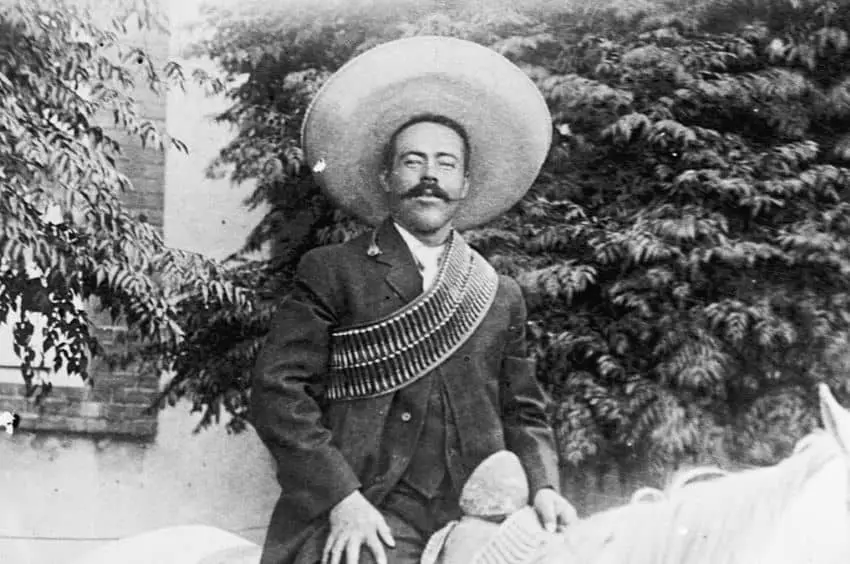

Born José Doroteo Arango and nicknamed the Centaur of the North Villa joined Francisco I. Madero to end the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. After Madero was assassinated in a coup d’etat by usurper president Victoriano Huerta, Villa led the fearsome Northern Division to victory over Huerta’s federal army. Echeverría’s tribute was a fitting one. The only problem was that the bones may not have been Villa’s — and his skull wasn’t there at all.

The theory espoused by some in Parral was that Villa’s last wife, Austreberta Rentería, had replaced the bones in his coffin with those of an unknown woman to thwart the repeated attempts of grave robbers. Meanwhile, Villa’s real bones had been secretly relocated to another grave 100 meters or so distant, where they remain today.

As for the skull, it has been missing since Feb. 6, 1926, when it was stolen from his original grave. Nearly 50 years after Villa was laid to a hero’s rest in Mexico City, though, many in Mexico feel certain they know who has it.

But officially, the crime is still a mystery, as is the person who ordered Villa’s assassination on July 20, 1923. Rest assured, however, there are suspects aplenty, including an elite university club whose members have included several U.S. presidents.

Is Villa’s assassination linked to the stolen skull?

When Villa was gunned down in an ambush in Parral in 1923, the assailants weren’t all unnamed. One of the admitted assassins was Jesús Salas Barraza, who spent only three months in prison before being pardoned by the governor of Chihuahua. Salas Barraza, it should be noted, was a congressman himself and was considered by many a puppet manipulated by his masters, then-president Álvaro Obregón and future president Elías Plutarco Calles.

Obregón had good reason for wanting Villa dead. Aside from the fact that Villa was rumored to be considering a run for the presidency, thus breaking the non-political oath that had allowed him to retire in peace in 1920, he and Obregón were old rivals. After a contentious Convention at Aguascalientes in 1914, when the revolutionary factions debated what to do after Huerta’s defeat, Obregón and Venustiano Carranza had allied themselves against Villa for leadership of Mexico.

The next year, Obregón defeated troops under Villa at the Battle of Celaya. However, during the subsequent Battle of León, Obregón lost his right arm — blown off during an artillery attack. It is conceivable then that Obregón would have wanted Villa’s skull, too, as a kind of payment for his own bodily loss. But he wasn’t the only one seeking a pound of flesh.

Why Americans had a bounty on Villa

Villa had many enemies in Mexico and plenty in the U.S. after a daring cross-border raid on Columbus, New Mexico in search of supplies for his army in 1916. U.S. Cavalry repelled the raiders but that wasn’t enough for President Woodrow Wilson. He assigned General John J. Pershing the command of over 6,000 soldiers for a punitive expedition to capture Villa and bring him to justice, even if it meant going into Mexico to get him.

This expedition increased political tensions between the two countries, with Carranza’s troops eventually firing on the Americans, and ultimately proved unsuccessful. Villa eluded U.S. troops for nearly a year, by which time Pershing had been reassigned as commander of the American Expeditionary Force for the First World War. “He came in like a proud eagle and left like a wet chicken,” Villa is said to have gloated.

Rumors of American bounties on Villa would continue even after his death. An unnamed U.S. organization was said to be offering $10,000 for Villa’s skull, twice what newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst was reportedly offering. Another group, the Yale secret society Skull and Bones, was also rumored to be seeking the skull for the collection.

The man who was arrested for stealing Villa’s skull

Only two men ever spent time in jail for removing Villa’s skull: American mercenary Emil Holmdahl and his accomplice Alberto Corral. Three days after scaling the wall of the locked cemetery in Parral, the two were locked up in the town jail. Enraged locals wanted to lynch Holmdahl. A man named Ben Williams helped to bail him out and get him across the border. A man of means, Williams was one of the investors who purchased the gigantic Palomas Ranch in Chihuahua, then the largest ranch in North America.

Williams’ version of events was later published in the 1984 book “Let the Tail Go with the Hide,” which leaves no doubt as to why Holmdahl stole the skull: it was for money. Holmdahl allegedly claimed the skull fetched $25,000 from a member of Yale’s Skull and Bones. Williams was so enraged when he learned this, per The Washington Post, he wanted to send Holmdahl back to jail in Mexico.

Skull and Bones, it should be noted, has in its historical membership some of the most powerful men in the United States, including not just scions of the Rockefeller and Vanderbilt families, but three former presidents: William Howard Taft, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush.

Is the Skull and Bones angle a conspiracy theory?

Yes, this does have all the elements of a conspiracy theory. However, evidence beyond Williams’ assertions suggests this story might be true. For starters, Skull and Bones does seem to collect skulls of famous people, including those of Villa, Apache leader Geronimo and former president Martin Van Buren. Prescott Bush, father of George H.W. Bush, was allegedly among the grave robbers who stole Geronimo’s skull.

Geronimo’s descendants are convinced Skull and Bones has his skull. As of 2009, twenty of his descendants had filed a lawsuit against Skull and Bones, Yale University and some U.S. government officials. Plenty of people buy the Villa story, too. In 1988, when The Washington Post repeated the Holmdahl story, a group of El Paso historians was mulling a lawsuit against Skull and Bones for Villa’s skull. In 2010, historians in Chihuahua asked the Mexican government to negotiate its release from Yale University, where they were positive it resided.

Many historians thus obviously believe the story is true. Two decades ago when journalist Alexandra Robbins interviewed over 100 Skull and Bones members for “Secrets of the Tomb,” her book on the organization, there finally seemed to be proof. Robbins affirmed that Skull and Bones did indeed have Villa’s skull. However, she soon recanted the claim in an interview with The Yale Herald.

So it’s still unknown to any degree of certainty. What is certain is that if Skull and Bones does have Villa’s skull, it doesn’t seem inclined to give it back.

Chris Sands is the Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best, writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook, and a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily. His specialty is travel-related content and lifestyle features focused on food, wine and golf.

Source: Mexico News Daily