Mohammad Rasoulof on Iranian censorship, fanaticism and love

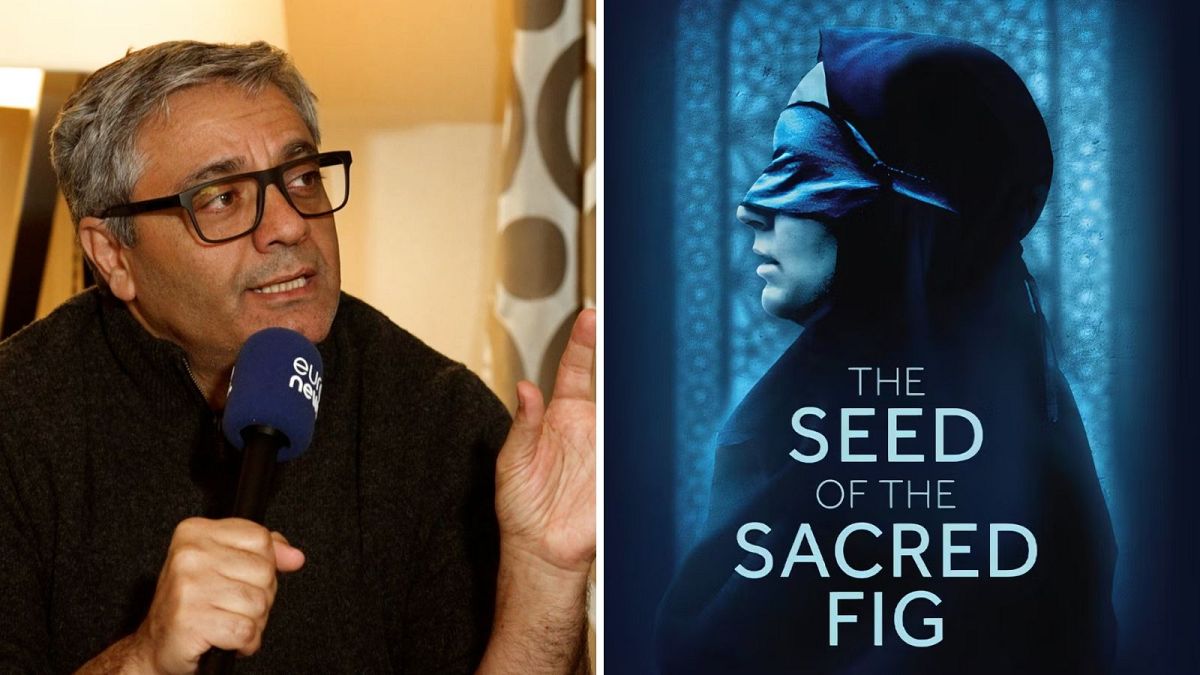

Dissident Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof fled his country this year in order to present his new film to the world and to keep working freely. He speaks to Euronews Culture about the year that changed his life and representing Germany at the Oscars.

A true standout in cinema this year was The Seed of the Sacred Fig by dissident Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof.

The film, set against the backdrop of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests of 2022, casts a critical eye on the consequences of life under authoritarian rule – much like his previous films Manuscripts Don’t Burn, A Man Of Integrity, and the Golden Bear-winning There Is No Evil.

It had its world premiere in Cannes, where it won the Special Jury Prize as well as the Fipresci award.

Beyond these accolades, the story of how he got to Cannes was the news that dominated headlines this year.

Days after finishing his film, shot in secret, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Court announced he was sentenced to eight years in prison and a flogging over charges linked to his earlier films and activism. His public statements, films and documentaries are considered “examples of collusion with the intention of committing a crime against the country’s security” by the judicial system of the Islamic Republic, whose repression and brutality has reached new heights when it comes to all artists.

Rasoulof had been in the crosshairs of the Iranian government before, having been banned from leaving Iran since 2017. He served four stints in prison, the most recent from July 2022 to February 2023 in Evin Prison, for speaking out against the government and in support of other arrested filmmakers. He was released due to general amnesty for thousands of prisoners in Iran following widespread protests.

His latest sentencing was the harshest in a series of arrests over the past decade – with no possibility of appeal.

Faced with this sentence, Rasoulof decided to flee his country, trekking for a perilous 28-days across a mountainous borderland before making his way to Germany – where he currently resides in exile.

It was only then that he managed to attend his film’s Cannes premiere – without some of his cast, who were banned from traveling. The Grand Theatre Lumière gave him a moving and lengthy 15-minute standing ovation – one which would have carried on had Rasoulof not taken the microphone to thank all those who made the film possible, including the ones who could not make it.

Since then, The Seed of the Sacred Fig has been selected by Germany as the country’s Oscar entry for Best International Feature Film.

Euronews Culture sat down with Mohammad Rasoulof at this year’s European Film Awards to talk about a year that defined his life, as well as the importance of remembering that many filmmakers are still working under censorship.

Euronews Culture: Mr. Rasoulof, we’ve been reporting throughout this year of not only your escape from Iran, but we were there in Cannes for this amazing standing ovation before The Seed of the Sacred Fig even began screening. I guess my first question is: After this trying year, how are you?

Mohammad Rasoulof: I’m fine, thank you so much for asking.

It was incredibly moving to see you on the red carpet in Cannes before the premiere. You secretly left Iran a few weeks prior, and to see you holding pictures of your cast who were imprisoned or facing imprisonment was very powerful. Do you have any updates on their wellbeing?

Yes, I am in touch with them. At the moment, the principal cast and crew are being investigated inside Iran on charges of spreading corruption and prostitution on earth, attempts against national security, and propaganda against the Islamic Republic. They will be in court for these charges.

Those pictures also showed that filmmaking is not just one person – it’s a multitude of people who are willing to sacrifice and put so much on the line in the name of art.

That’s exactly it. And in fact, the spirit of the work that brought us all together as a team was very much protesting against censorship, but also the desire that we all had to tell the story of a family without having to abide by the strictures and censorship and also going with artistic freedom. However, unfortunately, the regime always reacts in a very repressive and controlling manner. And that makes things very difficult.

However, I know that all filmmakers working under repressive circumstances will be free of them one day. And it’s important to remember that so many filmmakers inside Iran today are working within these very difficult conditions with censorship, the same that I was working in. And they’re transforming these immense difficulties into beauty. They are working well and we need to remember they’re working under very difficult circumstances.

How have you found the reaction of the international community and is enough being done to support you and your work? In Germany in particular, since you currently reside there, and where there is political turmoil at the moment…

Yes, I was supported by Germany from the very outset, because in fact, my family was already residing in Germany before I got there. So it was Germany that enabled me to travel from a neighboring country of Iran to Germany. And as you know, the film premiered at Cannes. Luckily, it did very well and the success of the film has been growing and growing since. And indeed, Germany decided to choose the film as its own submission as its own submission for Best International Feature Film for the Academy Awards. And I think that’s a great sign.

On the one hand, it shows that culture is always prioritized above politics, but at the same time it also shines a light in the darkness, inspiring filmmakers working under repressive circumstances all over the world, inspiring them and reminding them that there is an audience for their films out there.

What struck me about the film is how control and tyranny is masked by love – paternal and familial love in the case of The Seed Of The Sacred Fig. It’s very applicable not only just to Iran – it also has a universal value, especially at the moment when you see autocrats or wannabe dictators masking their desire for control through professing their concern for the supposed wellbeing of their citizens…

Yes. If love turns into submission to power or to ideology, that can very easily morph into fanaticism, which then very easily gives into violence. So, if we look at the story of the film, we’ve got two kinds of submission. There’s someone who out of love chooses to submit to political power and ideology. We then have his wife, who chooses to submit to him. We see how this creates this very fanatical atmosphere and leads to violence. It’s a specific and universal story. The devotion of some people to a system is a reflection you can have about many other places beyond the ones happening in Iran.

This year marked the two-year anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death. The film takes place during the protests, and one of the freedoms that we enjoy here in Europe is that we’ve been able to see the film, as well as another Iranian film My Favourite Cake, which was in Berlin earlier this year. What reactions have you had from any Iranians who have been able to see your film?

People had access to my film in an underground way, which is unavoidable when the Islamic Republic does not tolerate them officially. When my films are screened internationally – and it’s not just my films, it’s many other films, it’s all international films – then Iranians eager to watch them can find them through the internet, through social media.

What I can tell you is that My Favourite Cake has been extremely successful inside Iran. People have really loved it. Unfortunately, I can’t yet tell you what the situation of The Seed Of The Sacred Fig is because I’ve been away and it’s quite hard to get that kind of feedback right now.

But I’d like to flag up the filmmakers of My Favourite Cake, Maryam Moghadam and Behtash Sanaeeha, are undergoing all sorts of problems inside Iran. They are banned from leaving the country because of their films, and in fact, they are being investigated for similar charges for spreading prostitution and corruption on Earth, for instance. This atmosphere will be the cause of a series of new problems because in the world now, it’s not possible to control content, like the Iranian regime does. The result of this is more and more repression, and acts of subversion will surface, as the government cannot control everything.

Filmmaking, in and of itself, is an act of hope. We see that hope with the two daughters in the film, Rezvan and Sana, who represent change. Beyond filmmaking, how do you keep that hope alive, especially considering the continuing violent repression in Iran?

It’s very important to give meaning in life and to do meaningful things. The necessity for freedom, that I feel extremely strongly, gives meaning and fills me with hope. I’d say that it’s the necessity for freedom that gives me the most hope.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig has had an enormous amount of success, not only in Cannes but like you said as the German submission for the Oscars. Going forward, what are your ambitions for next year – and the years to come?

When I reached these high cliffs, on the border between Iran and a neighboring country, I looked back for a moment and I thought, there’s no way I can take one more step, because I was – and I am – so tied to that land. Its geography, its people, its culture. And yet, I knew that I had a long prison sentence awaiting me. And if I were to remain, I’d have to go to prison for a long time, and I wouldn’t be able to do very much as a filmmaker. I wanted to keep working, so that’s why I kept walking. And that’s what motivates me.

What I do hope is to be able to keep working now that I’m in a safe place and also have the set up necessary to work freely. I’m in an atmosphere where I can work with a certain freedom. I’d like to keep working in the same vein that I’ve been reflecting and working in for many years. I’d like to keep telling stories that very much have to do with what’s happening inside Iran, yet tell them in a way that watching them can be joyous for anyone, anywhere in the world.

Check out extracts from our interview with Mohammad Rasoulof in the video at the top of this article. Stay tuned to Euronews Culture for our end of year Best Movies of 2024 list.

Source: Euro News