Public transport in the heart of the metropolis

“The train car is the street, the Metro is the city, the ticket is the password to immerse yourself in the assembly of people, the crowd is the origin of the species, and the passenger (myself in this case, or any of the six million who come and go each day) accepts the hardships of coexistence.”

— Mexican writer and chronicler extraordinaire of Mexico City Carlos Monsiváis in his essay “Sobre el Metro las coronas.“

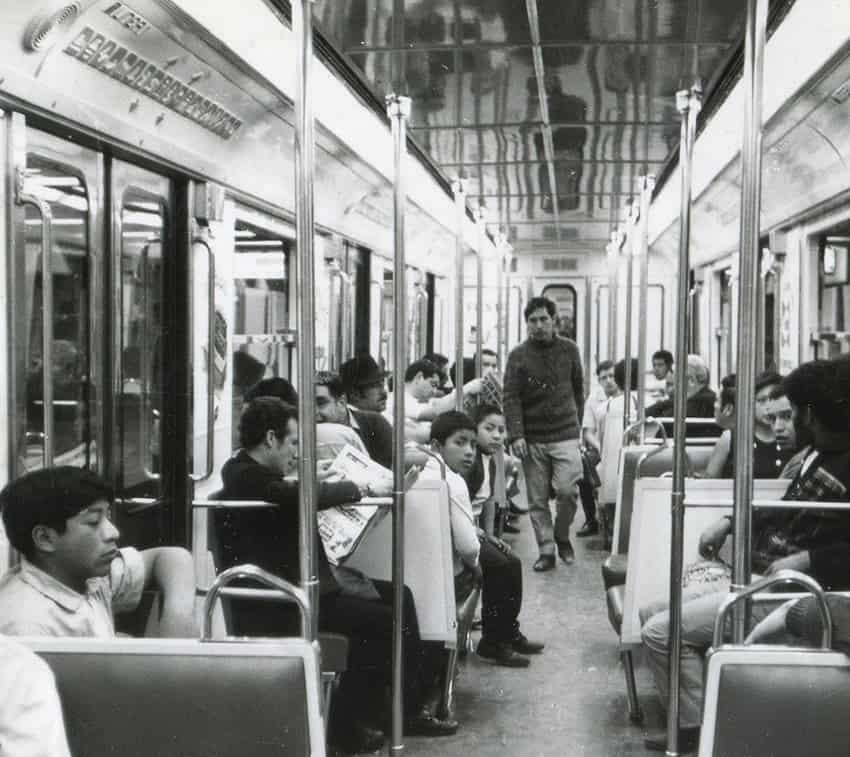

Apart from your most intimate relationships, you’re unlikely to get so close and personal with other people in Mexico City as you do when riding the metro system during peak hours.

Passengers took more than 1.1 billion trips on the Mexico City Metro last year, equating to 3.2 million journeys per day. Not quite the six million passengers Monsiváis referred to in his 1995 essay, but it can certainly feel like that is the correct number when your body is pressed up against one or more of your fellow travelers at 6 p.m. on a Friday evening.

The Mexico City Metro system is an immense art and anthropology museum, it is a bustling marketplace where all manner of goods and services are available for purchase, but first and foremost it is a massive public transit system, the backbone of a more expansive network of transporte público in the sprawling metropolitan area of the capital.

12 lines, 163 stations, 20,000 days of service

Intermingling psychedelic worms — a tangled assortment of multi-colored lines — superimposed on a white backdrop, stretching out over 11 of Mexico City’s 16 boroughs and into four municipalities of neighboring México state.

This is the map of the Mexico City Metro system.

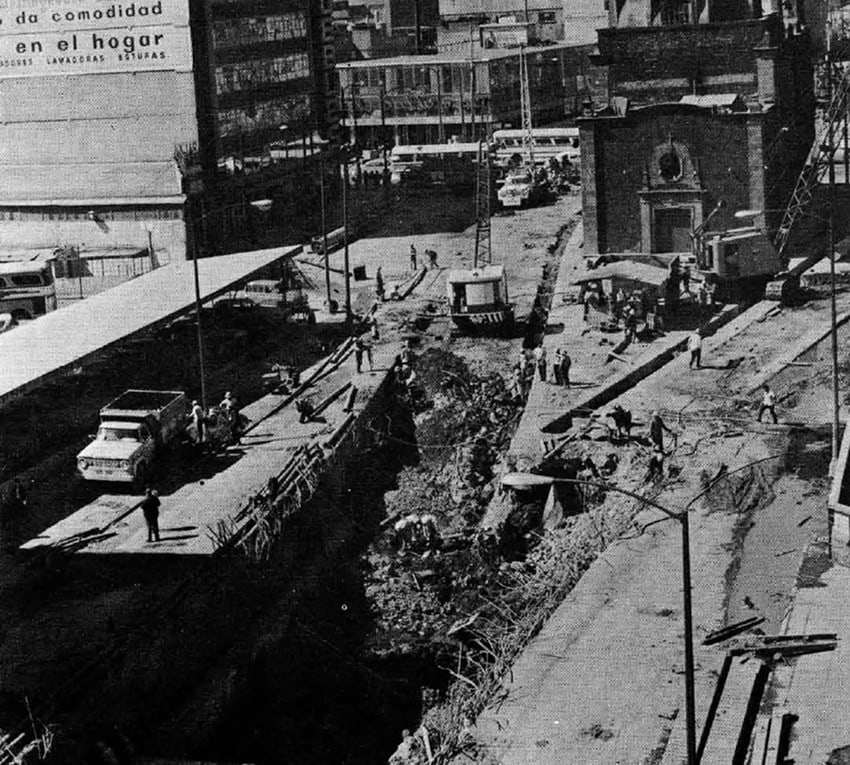

The system today — 163 stations on 12 color-coded lines spanning 226.5 kilometers — developed from what was originally just one line, the pink Line 1, whose construction began in 1967 at a time when Mexico City desperately needed more public transit options to serve the needs of a population that grew rapidly in the 1950s and ’60s.

Twenty-seven months later, the work of 12,000 engineering experts and laborers was complete, and the first service ran between the Zaragoza and Chapultepec stations on Sept. 4, 1969, with both president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and Mexico City mayor Alfonso Corona del Rosal on board.

Since that date, the Mexico City metro has operated every single day, meaning that it has now transported passengers on more than 20,000 consecutive days across a period of almost 56 years.

After the inauguration of Line 1 in 1969, more lines opened in the following years and decades until the system reached its current size when Line 12 — the golden line — began service in 2012. One of the Mexico City Metro’s worst-ever disasters occurred on this line in 2021 when two train carriages plunged onto a busy road in the capital’s southeast due to the collapse of an overpass. Twenty-six people were killed and close to 100 were injured.

There have been other accidents over the years, including a 1975 collision between two trains at the Viaducto station on Line 2 that claimed more than 30 lives.

The rapid — or arduous — commute

With a population of well over 20 million people in its metropolitan area, Mexico City needs more than a subway system to move its citizens.

The other public transit options — including Metrobús, light rail, suburban train, trolley bus, pesero and soaring cable car services — not only supplement the Metro but complement it as well, as many of their stations and stops feed passengers into the subway system, allowing them to complete their journeys.

In Mexico City, a public transit ride can be a quick zip up a metro line, and it can also be an hours-long, patience-testing odyssey (or ordeal) involving various modes of transportation. Commuters who come into central Mexico City from the surrounding metro area municipalities of México state face some of the longest trips.

One such person is Maura Hernández, a domestic worker who lives in the México state municipality of Nicolás Romero, located around 40 kilometers northwest of central Mexico City.

She told Mexico News Daily that she travels up to two hours by bus or “combi” just to reach the Cuatro Caminos Metro station in Naucalpan, México state, from where she completes her journey to the homes at which she works in Mexico City neighborhoods including Del Valle and Polanco.

It takes Maura up to three hours to reach her workplaces from her home, meaning she can spend as many as six hours per day on public transit in Mexico City and México state. With such long journeys, it’s no surprise that many commuters take the opportunity to catch up on sleep — if they’re lucky enough to nab a seat.

While her trip by metro is the shortest part of her urban odyssey, Maura noted that is often the most uncomfortable.

“It’s very crowded,” she said, noting also that the trains sometimes stop for as long as 10 minutes — a common frustration for metro users.

While long commutes are a fact of life for Maura and many other commuters, a new form of transport in Mexico City is reducing travel times for some.

The capital now has three Cablebús (cable car) lines that whisk passengers through the air and deposit them near the Indios Verdes (Cablebús Line 1), Constitución de 1917 (Line 2), Santa Marta (Line 2) and Constituyentes (Line 3) metro stations.

Last Friday, I made my way by metro out to the eastern terminus of Cablebús Line 2 at Santa Marta, located around 20 kilometers southeast of downtown Mexico City at a point where the capital meets México state. From there I took the approximately 40-minute ride to the western terminus at Constitución de 1917, where the metro station of the same name is located.

As I flew over the cinder block sprawl of the densely populated Iztapalapa borough, looking down at colorful murals, clothes drying in the high-altitude sun, countless “roof dogs,” roosters, hens and even urban swine, I spoke to a number of Cablebús passengers, all of whom told me that the four-year-old cable car line saves them a considerable amount of time compared to their previous commutes.

Enrique and Concha, a couple, said that their children also use the cablebús to get to school, thus avoiding a slow bus or combi ride to the Constitución de 1917 Metro Station through streets that are often winding and bumpy.

Another benefit, Enrique noted, is that the cablebús contaminates far less than many other forms of transport, significantly reducing emissions in a city known for its poor air quality.

Ricardo, a tattoo artist, uses the smooth and almost-silent cablebús on a near daily basis to reach the metro and continue his commute to his workplace east of the historic center of Mexico City.

The Iztapalapa resident said the cablebús shaves an hour or more off his traveling time, and declared he had absolutely no complaints about the service. He said it wasn’t feasible for the government to extend the metro system into the hilly terrain over which much of Cablebús Line 2 runs, and therefore the next best thing was to have an aerial transport system that avoids traffic and connects to the subway at both ends.

Citing Mexico City’s Mobility Ministry, Bloomberg reported late last year that “the Cablebús system has more than halved trips that used to take an hour and a half by bus or taxi.”

Crowds are not a concern for commuters on this form of public transit as each car is limited to 10 people, all of whom have a designated seat. Stepping out of a cable car and into a metro train just minutes later can indeed be a jarring experience.

The subterranean class divide

Smart business clothes are definitely not the most common attire worn by metro passengers, and indeed the archetypal rider of the system is not a well-paid businessperson.

In fact, most well-to-do capitalinos and chilangos choose not to go underground to use the metro, instead preferring to battle the traffic-clogged streets in their own vehicles, in a ride-share, or even in a chauffeured car if they (or their family) has the means to pay a private driver.

“A significant sector of the middle class and above simply don’t consider” public transport in Mexico City “an option,” VICE News reported in 2016.

Beneath the city — and “beneath me” — is the attitude of many middle and upper class Mexico City residents.

“It’s very different for people to be seen arriving in their own car than having to say that they use the subway or a pesero,” Ivonne Acuña Murillo, a sociologist, told VICE.

In addition to an understandable lack of desire to contort oneself into an uncomfortable position in an overcrowded train car, crime on public transit, including the metro, is also a concern for Mexico City residents. The fear of becoming a victim has only intensified recently due to a series of needle attacks in trains.

Still, the metro remains an indispensable way to get around the capital for millions of daily commuters, who part with 5 pesos (now deposited onto an “integrated mobility card” rather than exchanged for a paper ticket) and put their faith in the system to get them to work, to school, to university, to hospitals and health care clinics, and to countless other places on time.

“The low fare has made it one of the primary modes of transportation for the city’s working class, who use it in combination with other forms of public transportation to reach jobs in distant parts of the metropolis,” states the 2018 academic paper “The Mexico City Metro and its Riders.”

All kinds of workers use the metro to get to work — even clowns such as Agustín, who I met on a recent trip on Line 12. He told me that he uses the metro to get into central Mexico City from the southeastern borough of Tláhuac, where he lives, to entertain children at facilities operated by the DIF family services agency. Given that he asked me for some spare change at the end of our conversation, I concluded that while he may well have a talent to get people rolling in the aisles, he’s not exactly rolling in it himself.

But at just 5 pesos (about US $0.25) a trip, the Mexico City Metro is one of the most affordable mass transit systems in the world, meaning that even the most economically-stressed people can generally join the underground parade and perhaps get themselves to a job where they can work toward improving their financial situation.

According to the 2009 paper “Is the Mexico City Metro an inferior good?” the Mexico City metro “adopted a low fare mechanism with the provision of only one type of ticket regardless of the distance travelled so that the poor peripherally located population could afford the service.”

So is the metro, as the aforesaid article asks, an inferior good for Mexico City residents — an item (or service) that becomes less desirable as the income of consumers increases?

People’s class — or perhaps better put their purchasing power — is, in many cases at least, the determining factor in how they see the metro.

Through research, modeling and other methods, the authors of the “inferior good” paper found that “for the majority of metro users, whose salaries are based on low multiples of the minimum wage and are not potential car owners, the Mexico City metro is perceived as a normal good.”

“However, for middle/high income earners, who can afford to buy a private vehicle when their incomes increase, the Mexico City metro is perceived as an inferior good,” the paper said, providing an academic explanation for the subterranean class divide.

The rider experience, from the first car to the last

I have been a regular passenger on the Mexico City Metro for over a decade, using the system at almost all times of the day (it closes between midnight and 5 a.m.) to move around the enormous capital.

Yes, on plenty of occasions I have suffered amid a sea of fellow passengers jam-packed into a train car. Yes, I have been a victim of crime — my cell phone was once pickpocketed while riding Line 1 in the morning rush. Yes, I’ve grown frustrated as I stood on the platform and watched crowded train after crowded train go by without any possibility of getting on myself.

🇲🇽 México Mágico en el metro 🇲🇽 pic.twitter.com/wCgdRBbudE

— 🇲🇽 México Mágico ✨ (@EnMexicoMagico) January 13, 2020

A young man even once whispered “fuck you” into my ear for no discernible reason as I alighted a train.

But all in all I’ve had a great experience riding and passing through the stations of the Mexico City Metro. I’ve enjoyed the amazing art, I’ve gotten to where I needed or wanted to get and the train cars in which I’ve traveled have mostly been clean.

I’ve also witnessed some incredible in-carriage performances — including, I should say, some very confronting ones in which mainly shirtless men purposefully harm themselves by throwing themselves onto shards of broken glass in an attempt to shock passengers into handing over a coin. A whole other story.

I am, of course, aware that the experience of riding the metro can be very different for men and for women, who face a greater risk of sexual harassment and abuse.

One initiative aimed at ensuring the safety of female passengers is the designation of “women only” metro cars, which were first introduced in Mexico City in 1970, the year after the system opened.

The initiative was formalized and expanded in 2000, with access to the first two cars on trains running on several lines limited to women and children under 12 during designated periods of the day. While the success of the initiative has been limited, and sexual harassment and abuse still occur on the metro, women-only metro cars do offer some “respite” for women in Mexico City, if not from the crowds, as journalist Madeleine Wattenbarger wrote in a 2017 essay for Literary Hub.

“The women’s cars are no gentler than the others, or more spacious, or less crowded. If anything, passengers push each other more persistently, unfettered by any fear of indecency that may lead men to defer every so often. Still, I find them sororal and collaborative. When I can’t reach a pole to grab for balance, a woman offers me her shoulder,” Wattenbarger wrote.

“It would be foolish to entertain the notion that the overwhelming female-ness of this space guarantees its safety. Still, I rarely inhabit public spaces that are so predominately female; rarer still do I find spaces designed to be that way. … In the women-only car, though, I experience a respite, however fleeting and illusory, from the anxiety of carrying around my body.”

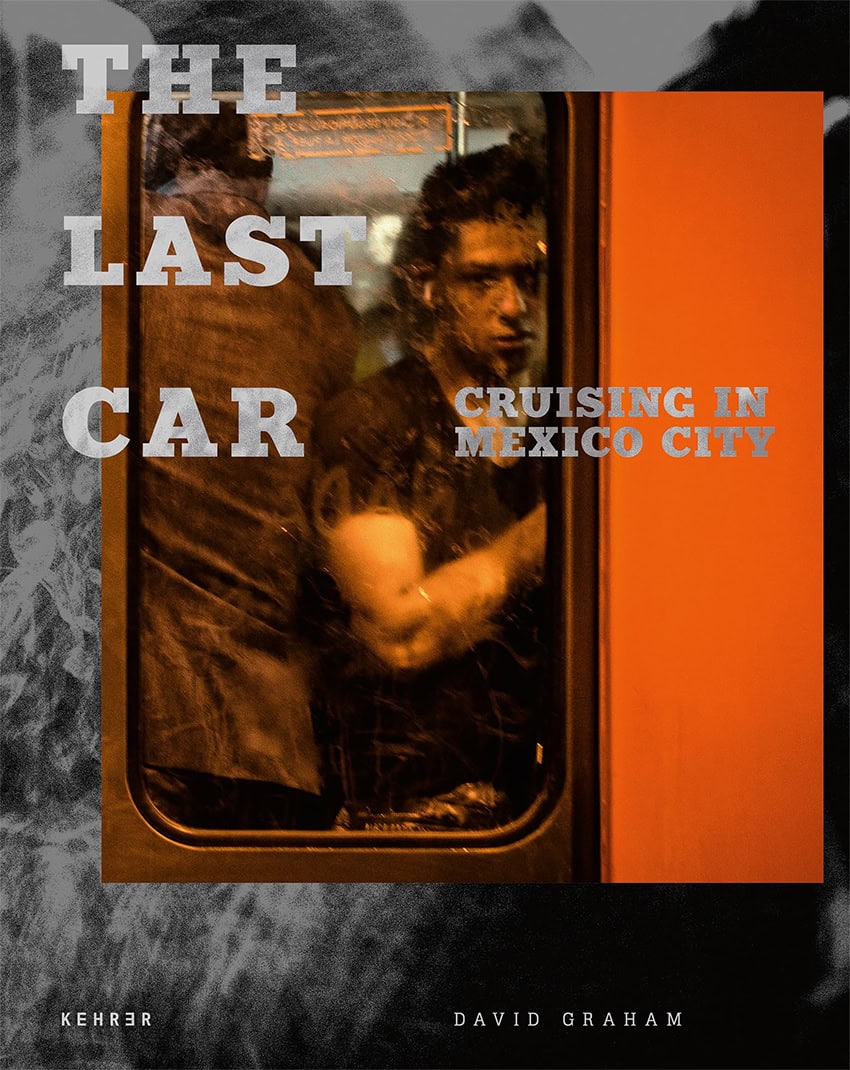

While a sororal bond might unite female passengers at the front of the train, male metro users sometimes come together in an altogether different way at the back. The final car, or último vagón, of metro trains in Mexico City is known as a gathering place for gay men, a mobile cruising ground where first encounters can quickly turn erotic.

“I had heard rumors about men having sex in Mexico City’s subway system. But nothing prepared me for what I witnessed on my first ride in the último vagón,” wrote author and academic A.W. Strouse in an article published by The Nation last December.

“… The historian Alonso Hernández Victoria notes that gay men have used Mexico City’s subway for sex, romance, and other encounters since it opened in 1969,” Strouse wrote.

The occasional homoerotic culture of the último vagón was also explored by photographer David Graham in his 2017 book “The Last Car: Cruising in Mexico City.”

Moving people, driving forward the economy

Given that it moves so many workers on a daily basis, the economic importance of the Mexico City Metro system cannot be overstated.

It is transport system that is “absolutely necessary for the functioning of the urban economy as a whole,” academic Diego Antonio Franco de los Reyes wrote in an article published by Revista Común.

In an article for Nexos, economist Carlos Brown Solà described the metro as “the heart that makes the metropolis beat.”

That metropolis is Mexico’s economic powerhouse, generating close to 15% of Mexico’s total GDP in 2023. Add in neighboring México state, which includes many municipalities that are part of the Mexico City metropolitan area, and the share of national GDP increases to around 24%.

Without a generally reliable subway system that quickly gets millions of workers to their workplaces on a daily basis, Mexico City’s economic capacity and productivity would no doubt be significant diminished.

Public transit in general “provides mobility options, generates jobs, spurs economic growth and supports public policies regarding energy use, air quality and carbon emissions,” according to the American Public Transport Association.

In Mexico City, the metro system has helped to connect informal sector workers to formal jobs, according to World Bank research economist Román David Zárate.

The construction of Line B of the Mexico City metro, which was completed in 2000 and links central Mexico City to Ecatepec, México state, “sent broad economic ripples through the local housing and labor markets, leading informality rates to fall by as much as seven percent in locations close to the new stations,” said a World Bank article based on research carried out by Zárate and others.

“When new transport infrastructure such as Bus Rapid Transit or metro lines reduce travel time between locations, new places gain access to jobs and the formal labor market becomes more attractive,” Zárate said.

Around half of all workers in Mexico City work in the informal sector, but without an expansive metro system that provides people with easy access to formal employment hubs, research indicates the percentage would be even higher.

The future of the Mexico City Metro

There are currently no plans to add new lines to the Mexico City Metro, but the prime public transit system in the Valley of Mexico, and the transport tributaries that flow into it, continue to expand.

Work has begun on the expansion of Line 12, which will connect with the Observatorio station on Line 1 when the project is completed, perhaps in late 2027. Sometime later this year, the new Toluca-Mexico City train line will reach Observatorio, allowing passengers to immediately access the metro system and thus reduce their total travel time between the México state and national capitals.

Also in 2025, Mexico City residents and visitors will be able to travel to the Felipe Ángeles International Airport in México state from the Buenavista Suburban train station, located just outside the historic center and adjacent to the Buenavista metro station.

Like millions of metro passengers, these infrastructure projects have faced delays.

But just as the gusanos naranja (orange worms) — as the metro trains are colloquially known — invariably resume their forward progress after stoppages and reach their final destinations, so too will the transit projects. Have faith that, in time, they will help propel passengers, the economy, the city and even the nation of Mexico as a whole to where they need — and want — to be.

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies ([email protected])

* This article is the third and final part of a Mexico News Daily series on the Mexico City Metro. Follow the following links to read parts 1 and 2.

Source: Mexico News Daily