Remembering the Battle of the Alamo

“Remember the Alamo” became a battle cry in the Texans’ struggle for independence from Mexico, but the Battle of the Alamo was, in fact, a small engagement, with fewer than 200 Texans confronting a few thousand Mexican troops. While the story of the siege is well-documented, the lead-up to the battle has largely been neglected.

The same energy that brought Hernán Cortés to the land of the Mexica also took conquistadors further north, claiming Texas and a vast area of what is now the U.S. for Spain. This remote area attracted limited European migration, and the small numbers of settlers were never able to subdue the Indigenous people as firmly as Cortés and his handful of warriors had decimated the Mexica. As late as the 1800s, there were still only approximately 3,500 settlers living in the whole of Tejas. It didn’t even merit its own governor but was a neglected northern section known as Coahuila y Tejas.

Spanish Texas becomes Mexican

On the surface, little changed after Mexico gained independence in 1821, Spanish Texas simply becoming Mexican Texas. However, the region had been dependent on Spain for money, priests and manufactured goods, and Mexican independence saw the local economy shrink. Smugglers filled the gap for imported goods, and rancheros drove their cattle north to the illegal but more profitable U.S. markets.

To increase the number of settlers, Mexico encouraged migration from the U.S., and in January 1821, Moses Austin was granted permission to bring the first 1,200 families from Louisiana to Texas. Twenty of the first 23 such settlements were populated by immigrants from the U.S. These new communities tended to be self-contained, and people maintained a close affinity to the U.S. One area of conflict was the keeping of enslaved people, a practice Mexico had outlawed, but which many new colonists felt essential to their prosperity. The Mexican government, seeing itself becoming outnumbered in its own northern territory, introduced the Law of April 6, 1830, prohibiting any further immigration by U.S. citizens.

The escalation of tensions

The situation simmered until 1833, when Antonio López de Santa Anna was elected president of Mexico and abolished the Constitution of 1824. This moved Mexico towards centralism. For Americans living in Texas, it was both a cause of concern and an excuse to start dreaming of independence. In 1835, Martín Perfecto de Cos, a man related to the Mexican President by marriage, arrived in Texas with 500 soldiers to shore up Mexican rule. After several small confrontations, events blew up in the Texas town of Gonzales.

The community had been loaned a small cannon for protection against the Native Americans, and with tensions on the rise, the Mexican government sent a strong force — 100 cavalry — to reclaim their artillery piece. The soldiers arrived at the Guadalupe River to find a small group of armed Texans on the other bank. The men refused to return the cannon, and as the Mexican army searched for a crossing point, more and more men rode in to confront them. A shot was fired, and the Mexicans, now outnumbered, retreated without the cannon. Nobody realized it at the time, but the Texas Revolution had started.

The Texas Revolution

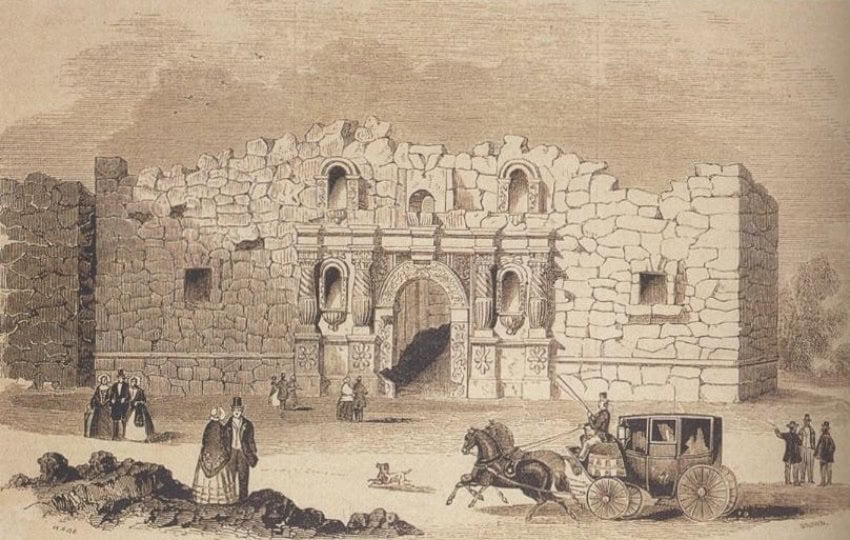

At this stage, unrest in Texas was less a political movement and more a general rumbling against taxes and central government, but buoyed by their success at Gonzales, a mob of Texans marched towards San Antonio de Béxar. The town had a population of around 2,000, mostly Spanish speakers who supported Mexican rule but were largely unpolitical and just wanted to get on with life. The community centred around the plaza and cathedral, and just one block from the center, you would find simple houses that sat on the edge of their own cultivated fields. In response to raids by the Native Americans, there were several fortified missionary buildings, including the Alamo, which was separated from the main town by the San Antonio River.

The Texans, who were described at the time as “a motley bunch of ruffians with fewer guns than men, short on powder and lead, with no heavy artillery to brag about,” made camp just outside San Antonio. At this stage, the “rebels” lacked any government or a clear list of demands. While some talked of independence, others only wished for a degree of local autonomy. Stephen Austin, a Virginia-born landowner, led a team to negotiate with General Cos.

When no arrangement could be reached, the general, under pressure from the Mexican government, and with the larger force, felt compelled to act. On an early morning in October, he led a force of around 270 men towards the Mexican camp. A small force of Texans took up a strong position on the banks of the San Antonio River and in just 30 minutes fought off three Mexican assaults, forcing the bigger army back into the town.

‘Who will go with old Ben Milan into San Antonio?’

Nothing had really changed. Cos and his army were still besieged, and the Texans were still too small in numbers to launch an assault on the town. In the Texan camp, boredom was now the greatest danger; men who were volunteers simply slipping away and going back to their farms. This was a pattern that could be expected to worsen as supplies dwindled and winter approached. The Texans were considering decamping and seeking winter billets when a Mexican deserter brought news of the situation in the town. The troop’s morale was low, he reported, and they were running short of both food and water. Colonel Ben Milan offered to lead an attack and, having been given permission to do so, called for volunteers. “Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?” was his famous cry.

After six weeks of siege and five days of house-to-house fighting, General Cos retreated from the town, crossed the bridge over the San Antonio River, and took shelter in the Alamo. When he attempted to launch a counterattack, his cavalry deserted, and Cos sued for peace. The surrender terms were generous, the Mexicans even being allowed to keep their muskets for protection as they marched away.

The Mexican army in Texas had been neutralized, and many Texans now rode home, men such as young Creed Taylor, who arrived at his mother’s log cabin with a new horse, pistols, swords and silk sashes that had once decorated a Mexican officer’s uniform. However, back in Mexico, President Santa Anna had no intention of letting the Texans secede. Transferring his presidential duties to Miguel Barragán, he gathered an army in San Luis Potosí and started the march northwards.

Mexican army on the march

It was a bitterly cold winter, the army lacked supplies, and many of the recruits, who had no military training, had to be given basic instructions on how to use a musket as they marched. There was no money to pay the civilians who worked the supply wagons, so many deserted. The decision to take the inland road, rather than work their way up the coast, meant the army was heading directly towards San Antonio, and as they marched, they met up with Cos and his retreating soldiers, who turned around and joined the column.

By now, Sam Houston was emerging as the leader of the Texan rebels, and aware that a Mexican army was gathering, he sent James Bowie to the Alamo with instructions to remove the artillery and blow up the fortification. Bowie discussed the issue with the Alamo commander, James C. Neill, and on Jan. 26, announced they would stay and defend the fort. There was, at this stage, no certainty that the Mexican army would even reach Texas, and the fort remained undermanned, under-provisioned and generally unprepared. Feb. 21st brought news that Santa Anna and the vanguard of his army had reached the banks of the Medina River, and with the Mexicans just a few days’ march away, San Antonio suddenly became a scene of hectic activity. While many civilians fled the town, the fighting men gathered supplies and herded their cattle into the Alamo.

Battle of the Alamo

The exact number of men in the mission is uncertain, but it was less than 200, while the Mexicans had around 2,000 troops, with more likely to arrive in the coming days. At 10 p.m. on March 5th, the 12th day of the siege, the Mexican artillery ceased their bombardment, and the exhausted Texans fell into their cots. They were unaware that Mexican soldiers were edging up to the walls to prepare a major assault. The attack came at 5 the following morning. Musket and rifle fire from the walls, and cannons loaded with a jumble of scrap metal, took a toll on the attackers, but a combination of numbers and bravery brought the Mexican infantry into the compound. By 6:30 a.m., the battle was over, and the defenders of the Alamo lay dead.

Mexico and Texas were now committed to war and a few weeks later, the Battle of San Jacinto would end in Texas independence.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life-term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.

Source: Mexico News Daily