Mexican Government’s Unique Christmas Tradition

Okay, so, before you start making weird assumptions: No, Mexican children do not write Christmas letters to Quetzalcóatl. Kids never have, and probably never will. Although ancient Mexica families did observe a religious veneration of the Lord of the Cosmos, Christmas was not even a thing in the Americas. Not before the Conquest, that is.

However! There was a time when, in an effort to purge Mexico of the “capitalist traditions of the United States,” the Mexican government tried to replace Santa Claus — the terrible symbol of unfettered capitalism — with our beloved feathered serpent. How on Earth did that happen, you may ask? Here’s a rather unorthodox Christmas carol. Mexican style, for your delight.

Did Quetzalcóatl ever celebrate Christmas?

The easy answer is no, not exactly. However, the winter solstice has been regarded as a holy moment across millennia in several ancient civilizations. The Romans, for example, celebrated Saturnalia, the annual festival to celebrate “the rebirth” of the year, during the winter solstice in the Julian calendar. Romans held raging parties with bacchanals, honoring Saturn, the God of Time and Harvest. Curiously enough, it was celebrated on Dec. 25.

Believe it or not, this Roman (and pagan) celebration has more to do with the Christian Christmas than Jesus himself. “The choice of December 25 as the date of Jesus’ birth has nothing to do with the Bible,” researcher Diarmaid MacCulloch, professor of Church history at Oxford University, explained to the BBC, “but was a rather conscious and explicit choice to use the winter solstice to symbolize Christ’s role as the light of the world.”

In this part of the world, the Mexica Empire also celebrated the winter solstice. However, they honored the birth of Huitzilopochtli, the God of War, who was also the solar deity of the Mexica pantheon. So yes, indeed, a “new coming of the light” was celebrated in pre-Columbian times, as documented by the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo researchers. Culturally referred to as Panquetzaliztli, this festival commemorated the god’s birth and the triumph of light over darkness.

Priests, artisans and civilians alike participated in ritual battles, processions and the distribution of an idol made of corn dough (tzoalli). So yes, the Mexica Empire did host an annual celebration for the birth of their solar deity. It was not Jesus, of course, and it was not Quetzalcóatl, either — however enthusiastic PRI politicians were about it.

Quetzalcóatl, the great Lord of… Christmas?

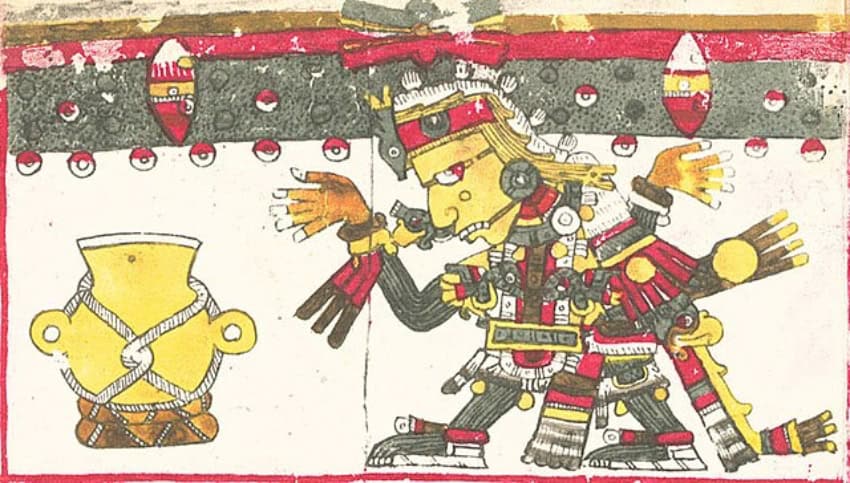

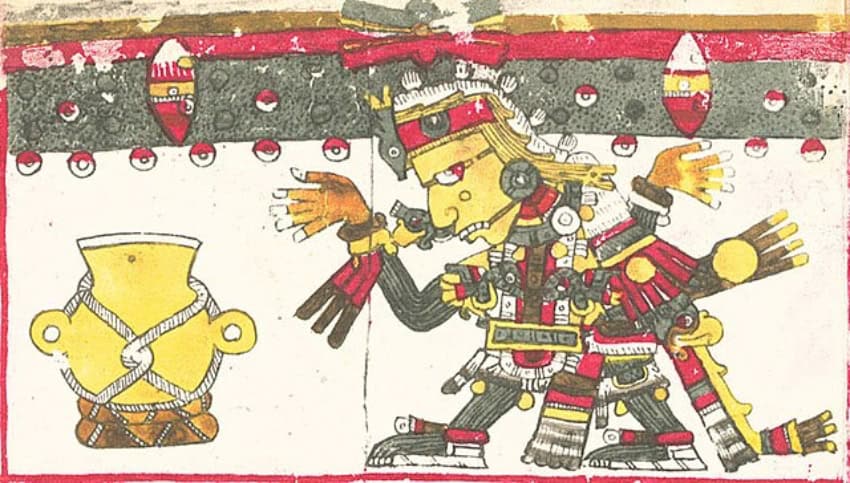

So, no. Quetzalcóatl has nothing to do with Christmas. At all. For centuries, he was venerated in the Mexica Empire as “the great blower that energizes the cosmos,” as documented by UNAM researchers. He was also considered the creator and destroyer of “the great cosmic eras,” which positioned him in “a fundamental role in the founding myths of this pre-Hispanic culture.” The sacred feathered serpent was often depicted as the Lord of the Winds in the form of Ehécatl as well.

Given the importance Quetzalcóatl had in the pre-Columbian worldview in present-day Mexico, some PRI politicians in the 20th century decided it was a great idea to consolidate national identity through these ancient deities. In their minds, nothing screams Mexico like Quetzalcóatl on Christmas Eve (what?).

It was 1930. The Minister of Public Education, Carlos Trejo y Lerdo de Tejada, agreed with former President Pascual Ortiz Rubio that it would be convenient to replace Santa Claus with Quetzalcóatl. “The idea was for a Mexican figure to instill in boys and girls a love for their race and culture,” according to Gaceta UNAM magazine. On Christmas Eve, you may ask? Yes. Exactly on Christmas Eve, the day on which all Christians across the world celebrate baby Jesus’ birth, Mexican children were urged by authorities to write letters to the sacred feathered serpent.

Giving away toys in the name of our Great Lord Quetzalcóatl

On Dec. 23, 1930, the Ministry of Culture organized a historic gift-giving event at Estadio Nacional, located in Colonia Roma. A replica of the temple dedicated to Quetzalcóatl was built for the occasion. That night, former First Lady Josefina Ortiz gave away toys, clothing and candy to children in need — all in the name of Our Great Lord Quetzalcóatl. Who needs Santa Claus, anyway? At the end of the ceremony, the hymn to Quetzalcóatl was sung.

No one liked the Quetzalcóatl-themed Christmas celebration. In a country where 97.7% of the population identified as Catholic (at the time), the event was seen as a sacrilege: “the intervention of a pagan deity in a Catholic celebration,” per Gaceta UNAM. Very few admitted they kind of liked the idea.

In the end, the idea simply didn’t stick, and poor Lord Quetzalcóatl silently returned to the Mexican holy pantheon.

Andrea Fischer contributes to the features desk at Mexico News Daily. She has edited and written for National Geographic en Español and Muy Interesante México, and continues to be an advocate for anything that screams science. Or yoga. Or both.

Source: Mexico News Daily