Analysis: Children can sue governments over climate change inaction, but don’t expect boom in Southeast Asia litigation

A CONTENTIOUS PROPOSITION

The UN general comment supports a developing trend of growth in climate lawsuits around the world, especially in the Global South – a term used to group poor or least developed countries including many in the Southeast Asia region.

Globally, the number of climate change-linked legal cases has soared to 2,180 in 2022, up from 885 in 2017, according to data from the Sabin Center and the United Nations Environment Programme.

In China, the country’s highest court in February issued a guidance that would encourage prosecutors to bring forward climate cases to pressure companies to follow environmental laws and help the nation reach its decarbonisation targets.

Despite this green light for the court to hear cases on a range of environmental matters, China – and most of the Asia region generally – is still lagging in bringing forward climate litigation.

Of the cases recorded across the world between 2017 and 2022, only a tiny fraction – 6.6 per cent – have originated in Asia, the highest in the region being 12 cases in Indonesia.

Last year, a high-profile case in the Philippines saw the country’s Commission on Human Rights find that fossil fuel companies were accountable for climate damage.

It means that those companies – which the commission found knowingly contributed to climate change, “a direct threat to the right to exist” – could be found legally liable for climate disasters in the country.

While the Commission’s decision is also not legally binding, it could set future civil liability in any action for loss and damage arising from climate change.

It was a rare success in what remains a sparse area of focus for law firms in the region.

Part of the reason could be a stigma – and lack of scientific data – that still hangs over climate change regionally. And for many governments, climate action and therefore litigation is seen as an impediment to economic development, experts say.

“I think in Asia and Africa, mostly, the litigators prefer not to use that language of climate change specifically, because they feel like it might hurt their cases,” Dr Tigre said.

Indeed, experts agree that launching climate litigation in Southeast Asia remains a contentious and problematic proposition for anyone, let alone children, to undertake.

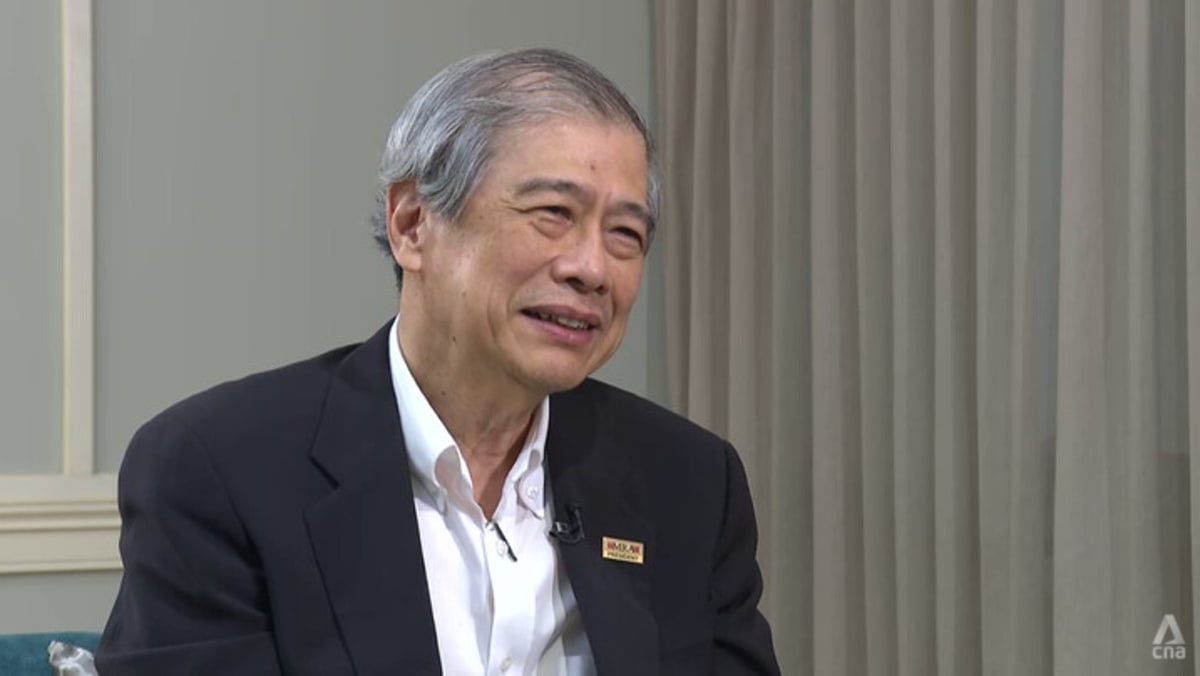

“What we’re seeing now, is a lot of interest in trying to explore various pathways to hold governments and corporations accountable. But my sense is that you won’t get an explosion of litigation in Southeast Asia,” said Associate Professor Jolene Lin from the Faculty of Law at National University of Singapore, who is also director of its Asia Pacific Centre for Environmental Law.

“Southeast Asia is not a monolithic region; every single country is slightly different in its legal conditions and the situation and the political context in which litigation will unfold.

“By and large, climate litigation is seen as unfriendly to governments who think that they are being challenged to do more and be accountable for their failure to do so.”

Yet, while the UN statement is not legally binding, it could further inform legal systems, national legislation and corporate behaviour, when it comes to environmental protection and children’s rights, say experts.

“It is a very encouraging development, because it opens up an additional potential pathway to bolster litigants’ claims,” Assoc Prof Lin said.

“When we talk about the development of climate change litigation, it’s important to recognise the improvement, or the creation, of additional support, like a scaffolding process. This adds to the scaffolding,” she said.

These rulings from international organisations may not have binding effect but they are an important source of legal guidance, she explained.

“States generally don’t want to be seen as pariahs. So, they will want to at least be seen to abide by these guidelines.”

Source: CNA