Can economics save Jalisco’s toxic Santiago River?

A new movement is afoot to clean up Jalisco’s Rio Santiago, widely considered one of the most — if not the most polluted river — in Mexico. And the charge is not being led by environmental activists but by a group of economists.

Well, ecological economists.

Salvador Peniche of CUCEA, the University of Guadalajara’s Center for Economic Sciences (under the leadership of Gustavo Padilla and Margarita Hernández) has teamed up with his colleagues in the International Society of Ecological Economics to issue a clarion call to government, business and the public at large:

“¡Verguenza! Shame!” they are crying out over the toxic waste and raw sewage that flows through what used to be one of Mexico’s most beautiful rivers before it was contaminated by an overwhelming number of toxic chemicals coming from one of Mexico’s largest industrial zones.

The Santiago River flows westwards from Lake Chapala via Ocotlán through the states of Jalisco and Nayarit to empty into the Pacific Ocean. It is one of the longest rivers in Mexico, over 400 km long.

The sad state of the Santiago made headlines in 2008 when 8-year-old Miguel Ángel López of El Salto, Jalisco, waded into the river to retrieve a soccer ball and died 18 days later, not from drowning but from having swallowed a mouthful of river water containing 400 times the amount of arsenic a human being can tolerate.

The public outcry resulted in the construction of the Ahogado sewage treatment plant in 2012. That reduced the amount of fecal matter in the river but did little about the more than 1,000 contaminants — including chrome, cobalt, mercury, arsenic, benzene, toluene and chloroform, just to name a few.

These heavy metals and synthetic compounds come from the second largest industrial zone in Mexico, located just above the river. In the zone, there are 600 plants producing everything from chemicals and steel to textiles and powdered milk. Many of them are owned by foreign companies.

Over the years, there have been numerous campaigns to stop these companies from polluting the river, including by Greenpeace. In the end, however, the river remains toxic, and the people who live alongside it in El Salto are paying the price.

They breathe the aerosols generated by the moving water, and they get sick. The incidence of cancer is several times higher in the municipality of El Salto than elsewhere in Mexico.

“See that street?” local resident Enrique Enciso says in the excellent documentary about the Santiago, “Silent River.” “There are eight houses on this block, and in six of them, somebody has cancer. “

The harm that the river’s contaminants are doing to the people of El Salto have made headlines for years, but no one has succeeded in cleaning up what many call “The River from Hell.”

So how is it that economists have now taken on this task?

I put this question to Peniche.

“We call this ‘shame economics,’” he says. “Basically, we want to demonstrate with satellite maps and with local sensors the deplorable state of the river basin and how it’s affecting people’s health. Then we want to make this public, and we want to calculate the cost of it all.”

These economists are calculating the cost of the services residents are not getting; the cost of the harm being done to nature, “the cost of so many people losing their kidneys; the cost of conjunctivitis; the cost of cancer,” Peniche explains.

They are interested in measuring all of these factors scientifically, he explains, “which is why we are working with satellite image experts, data managers, people who will help us get measurements — hard scientific data that we can present through the media.”

In other words, these economists want to quantify the scale and costs of the problem and give the public the scientific evidence it needs to act.

“What we are trying to do is to generate awareness here,” Peniche says. “As someone once wrote, ‘The silence we have kept greatly resembles stupidity!’”

Perhaps the best way to come to an awareness of this problem is to participate in what the people of El Salto call “El Tour de Terror.”

This is a visit to the Ahogado creek and dam, where raw sewage and industrial waste collect and work their way down to the river.

The tour is simply disgusting.

Stop number one is at a point where Guadalajara’s Periférico, or Ring Road, meets the main highway going to the city’s international airport. At the corner of two streets quaintly named Biblia and Rosario, we pulled up next to what looked like a drainage ditch.

We stepped out of the car to be hit by a stench that nearly gagged us.

This was the natural bed of the Ahogado creek, and raw sewage from countless houses all around us was flowing into it.

Our next stop was a spot only 100 meters north of the airport. Here we found great gobs of garbage floating on the creek’s surface. Amongst the plastic bags, worn-out tires and “icebergs” of Styrofoam, we spotted the bloated corpse of a dead dog.

Just across the highway from the airport, the river flows right into a grim-looking swamp called the Ahogado dam, which stinks to the high heavens. All around it are located hundreds of factories, and most of them seem to be spilling their residues into the smelly bog. Fat, filthy cows wander about the place, munching on the water hyacinths growing in the muck.

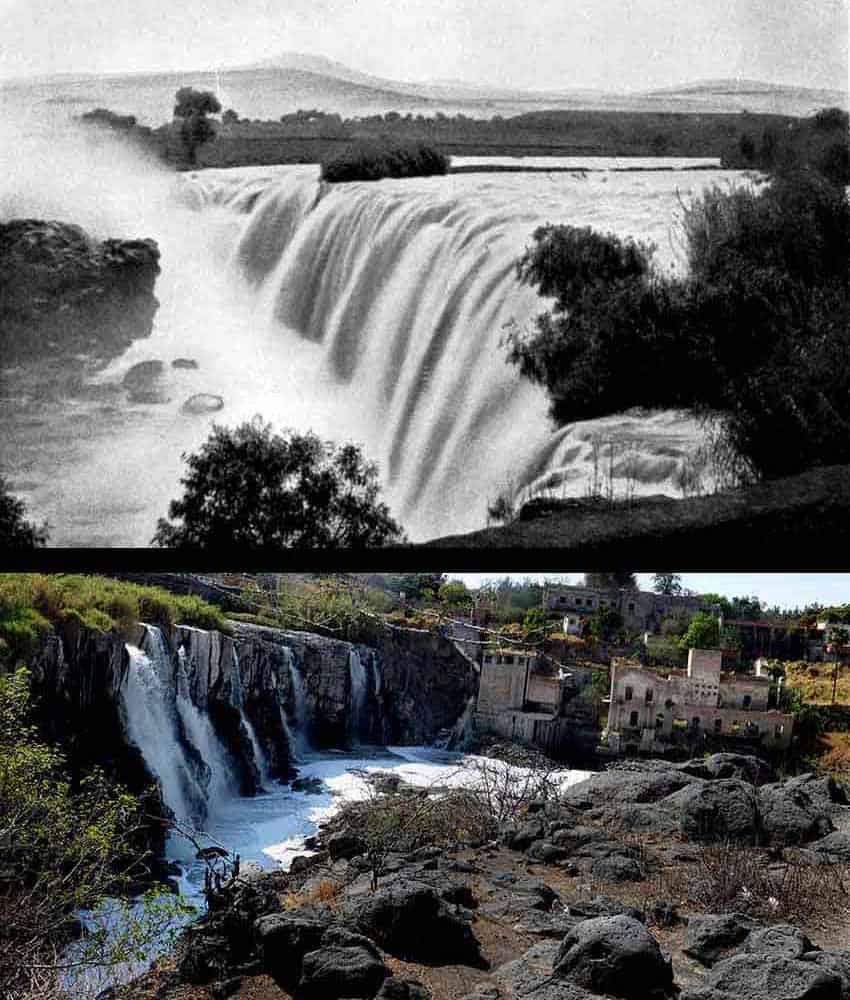

Finally we went to the most infamous point on the Santiago River, El Salto de Juanacatlán falls, once a huge tourist attraction nicknamed “The Mexican Niagara.”

Again, the stench. Amidst the falls’ corrosive spray, Peniche addressed our little group:

“This is everybody’s shame, the shame of the government, the industries, the university and the students. How is it possible [that] all of us have permitted a catastrophe of this magnitude!” he said. “We aren’t aiming at confrontation here. No, all of us, all the actors, need to work together in the recuperation of the river basin.”

Shame economics, as described by U.S. economist Paul Sutton and by Peniche, proposes the imposition of a universal tax — or as they refer to it, a duty — onto all factories near the river, based on their individual revenues: a “Collective Industrial Victim Impact Compensation Cost” (a CIVIC Duty).

“This financial levy,” say the two economists, “should be sufficiently painful to incentivize behavior change in the polluters. The beauty of a CIVIC Duty is that, as the river’s environmental qualities improve, the tax goes down. If the river gets worse, the tax goes up.”

“I think the public will like this,” adds Peniche, “because we are not blaming anybody in particular, but rather sounding an alert, to say, ‘Either we move full steam ahead on this or we’re all going to suffer.’”

Coming soon: Río Santiago: the Heavenly River — about the extraordinary natural beauty of the Santiago River and the loss in tourism dollars that its pollution has caused.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.

Source: Mexico News Daily