Dengue in Oaxaca: Mexico’s hidden epidemic

Every morning at the Dr. Aurelio Valdivieso General Hospital in Oaxaca city, infectious disease specialist Dr. Yuri Roldán Aragón visits patients. They may not be aware that the doctor they speak to is a living figure in medical history: in 2009, Roldán treated Mexico’s patient zero for the H1N1 influenza virus, alerting the world to a disease that would eventually cause the swine flu pandemic.

Today, Roldán’s primary concern is to find a pharmaceutical that can help those who are experiencing severe symptoms with the dengue virus, as patients with hemorrhagic dengue are currently treated with the same medications as those with basic dengue, such as paracetamol.

Dengue keeps breaking records

According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, around 13 million dengue cases and over 8,500 dengue-related deaths have been reported worldwide since Jan. 1, 2024. Nearly 12 million of these cases have been reported in the Americas, almost double the number registered in the region in 2023, which itself was the worst year ever recorded for dengue worldwide.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) issued an epidemiological notice in the first week of October, encouraging nations in the Americas to strengthen their dengue response strategies as cases spread throughout the continent. With 2024 expected to be a record year for incidence and the start of the dengue season in South America, PAHO emphasizes the importance of surveillance, early detection and adequate care in reducing severe cases and deaths.

Out of the over 11 million cases, 54 percent were lab confirmed, with 18.2 thousand of those affected having severe dengue, as stated in the epidemiological PAHO report of Oct. 4. In Mexico, 359,755 dengue cases were registered by the Health Ministry (SSa) between weeks one and forty of 2024. Most patients are cured within one to two weeks. Severe headaches, eye pain, articular and muscle pain and rashes are among the symptoms, which can range from moderate to severe and incapacitating. Symptoms often occur three to seven days following an infected mosquito bite. According to the journal of the Mexican School of Public Health (ESPM), 75 percent of people affected show no symptoms.

As stated by Yuri Roldán, the number of dengue cases started to grow in September of last year— he himself became sick. Much to his surprise, cases did not decline during the winter, as usually happens each year. The temperature did not drop enough to kill the disease-carrying insects, a reality which Roldán attributes directly to climate change.

Last winter and spring were likewise marked by a long period of severe drought. During the dry season, many people began storing water in containers inside their homes, creating a breeding habitat for mosquito larvae.

Given the increase in incidence and the prevalence of all four dengue strains in parts of the country, Roldán is particularly interested in finding a medicine to treat patients who are already ill, especially now that the DENV-3 strain has reemerged in Mexico after a decade.

According to the Health Ministry, comorbidities such as prior infections with another dengue strain, pregnancy or conditions such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension and kidney disease may cause the disease to progress to severe dengue.

Understanding the uniqueness of dengue

Dengue infection can be more or less severe depending on which serotype, or strain, a person is infected with. According to Yuri Roldán, one of the distinctive features of dengue is that if a person is bitten today by serotype 1, they would contract the disease, become resistant to it for the rest of their life and be protected against the other serotypes for a limited time.

Over time, however, these antibodies, which initially provided cross-protection against other serotypes, recognize the new virus serotype as a relative. Rather than helping to neutralize it, they promote its infiltration and reproduction, resulting in the production of more viruses and the onset of inflammation, thereby worsening the disease.

Roldán is exploring immunomodulatory medicines in order to find a medication to control the inflammation that patients experience.

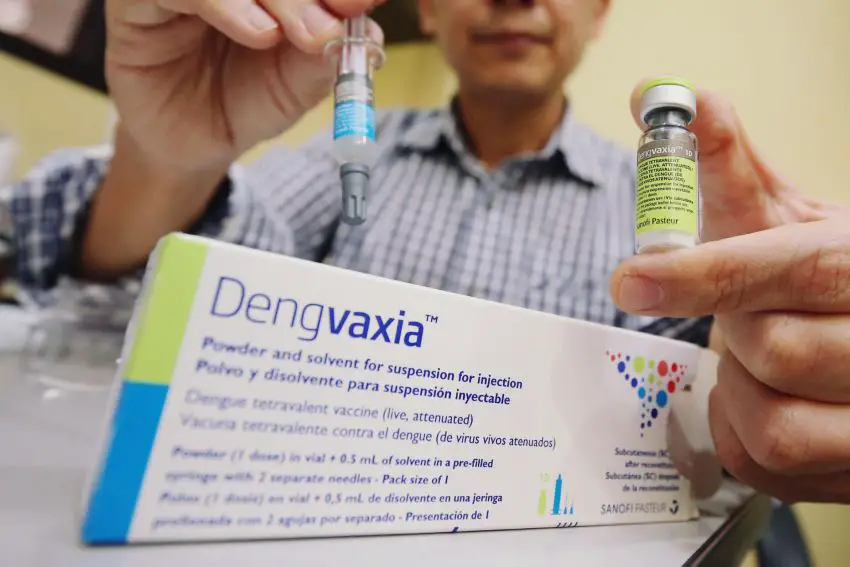

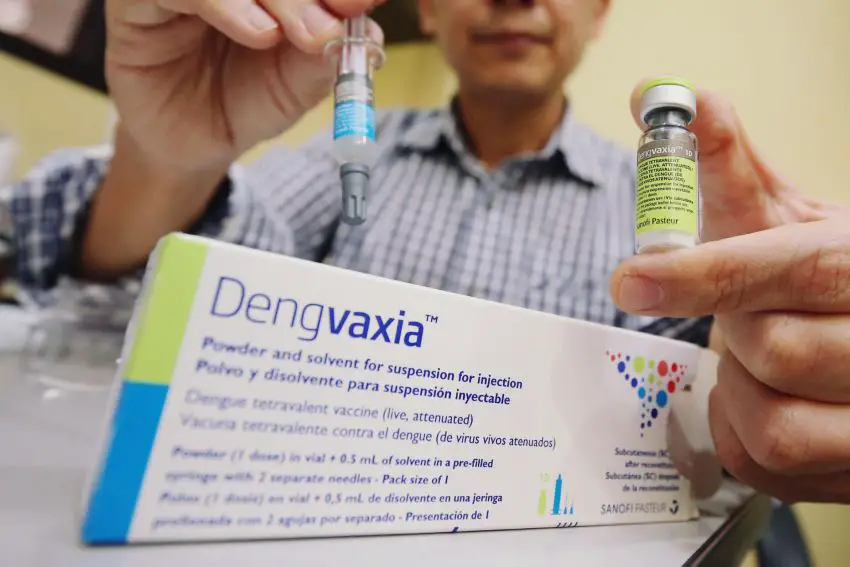

Dengvaxia, developed by the Sanofi Pasteur laboratory in France, is now the only vaccine approved in Mexico to prevent infection with all four dengue strains, or serotypes. The main disadvantage of this vaccine is that it can only be safely provided to people aged nine to 45 who have already contracted dengue. Because of these guidelines, it is not provided for free to the entire population of Mexico: it is only available through the private sector and costs $2,700 pesos each treatment, with three doses required.

Qdenga, also known as TAK-003, manufactured by Japanese laboratory Takeda, is another dengue vaccine that protects against all four serotypes. It is not currently accessible in Mexico, however, as it is awaiting approval from Cofepris, the federal health regulator.

Cooperation across countries is crucial in addressing epidemics and pandemics, with doctors from various countries working together to discover treatments. The Mexican Emerging Infectious Disease Clinical Research Network (LaRed), to which Roldán belongs, is an example of this. “We are preparing for any future infectious diseases that we may encounter,” the epidemiologist says.

Social anthropologist and photojournalist Ena Aguilar Peláez writes on health, culture, rights, and the environment, with a strong interest in intercultural interactions and historical and cultural settings.

Source: Mexico News Daily