Europe’s fiscal rules review – what does it mean?

Europe is aiming to rewrite its fiscal rules on government spending and taxes. In quite simple terms, it wants debt levels to be more sustainable.

The European Commission recently unveiled a proposal for the reform of fiscal rules in the European Union, which had been suspended during the pandemic but are now set to be reactivated and updated.

The public debt in the EU surged to 90% of GDP in 2020 due to the pandemic. Although it decreased to 84% in 2022, it still remains well above the limits set by the Commission.

Many countries have spent a lot of public money in recent years on measures to cushion the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine and the energy crisis.

What are the new fiscal rules?

The Commission’s proposal aims to grant EU member states greater control over how they meet the fiscal goals outlined in the EU Treaties. These goals include reducing public deficits to below 3% of GDP and public debt to below 60% of GDP. However, countries will be required to adjust their budgets by a minimum of 0.5% of GDP annually until they reach the 3% deficit limit.

“The objective is therefore a gradual reduction of public debt over 4 or even 7 years for countries above the limits, with a country-specific approach,” Paolo Gentiloni the European Commissioner for Economy told Euronews. “On the other hand, reduced fines would be effectively applied in case of non-compliance with the rules.”

It is expected that 14 countries, including Italy, France, Romania, Spain, and Malta, will exceed the 3% deficit limit in 2023.

Gentiloni explained that the Commission chose this approach because the previous fiscal rules were unrealistic and overly complex, which led to a lack of implementation. Having fiscal rules that exist only on paper is deemed unacceptable for the European Union.

“With a more gradual approach, I think we can achieve what unfortunately was impossible to achieve with the existing rules. It will not reach tomorrow the famous 60%. I think we should be open on this. But if the trajectory changes from an upward to a downward trajectory, this will be important for markets and for our union,” Gentiloni says.

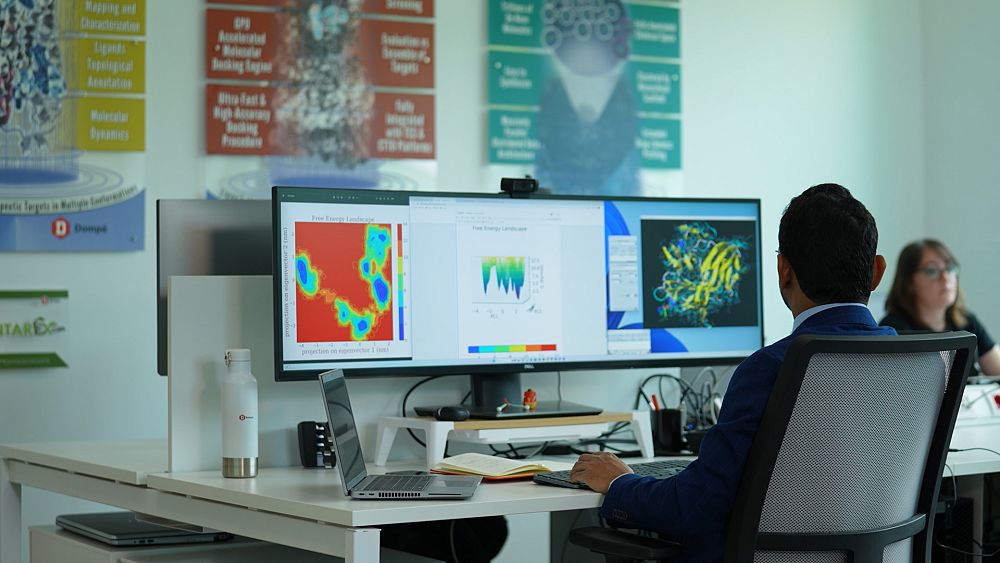

Investing in the digital transition

The importance of public investments in achieving these goals can be seen through examples like Italy’s supercomputer, Leonardo. With the joint funding of 240 million euros from the Italian Ministry of Universities and Research and the European initiative EuroHPC, Leonardo is set to contribute to many digital innovation projects. Such investments are vital for enhancing the competitiveness of European research and industry.

“Leonardo performs 250 million billion operations per second. Currently, it is the 4th most powerful machine in the world,” explains Francesco Ubertini, President of Cineca.

“The sectors in which Leonardo will be used range from weather forecasting, combating climate change, to accelerating the development of new drugs, and developing new digital twin products in general.”

Even though Italy’s public debt is already twice the threshold of budgetary rules, this investment aims to boost the competitiveness of Italian and European research and industry.

‘We need transparency and equality’

Economist Jeromin Zettlemeyer highlights the need for transparency and equal treatment in the debt reduction process while ensuring support for each country’s growth. Although concerns exist about potential abuses of discretion by the Commission, the proposed reform includes safeguards to ensure that debt is lower at the end of the four-year period. Zettlemeyer believes that the Commission’s proposal is coherent and suggests that the issue of transitory investment push be renegotiated.

“The fundamental idea behind this reform is to start and look at the circumstances of each country. The problem is that whoever exercises discretion in looking at those circumstances has a lot of power that can be abused. And the concern is by some member states that the commission might abuse it or whoever has political influence on the commission at the time,” Zettlemeyer says.

“Under the commission’s new proposal, there is a so-called safeguard that says no matter what happens at the end of those four years, debt needs to be lower than at the beginning. So that rules out a transitory investment push. That should be renegotiated. Other than that, I think the commission proposal hangs together.”

Ultimately, it remains to be seen how the reform will shape the fiscal landscape of the European Union, balancing the need for sustainable public finances with investments in crucial areas such as the green and digital transitions

Source: Euro News