How silk shaped the fortunes of China and Europe

In this episode, we travel between the silk cities of Suzhou in eastern China, and Lyon in southeastern France, to find out how this treasured material changed Eastern and Western culture.

The cities of Suzhou in eastern China and Lyon in southeastern France are two of the world’s most renowned silk centres. In this episode of Crossing Cultures, we explore the ancient ties that bind both China and Europe and learn from the artisans keeping the craft of silk weaving alive.

For nearly five thousand years, the city of Suzhou has been synonymous with China’s silk industry. Known as the Venice of the East, grand canals and gardens are a lasting reminder of the wealth the city amassed through its trade with the rest of the world.

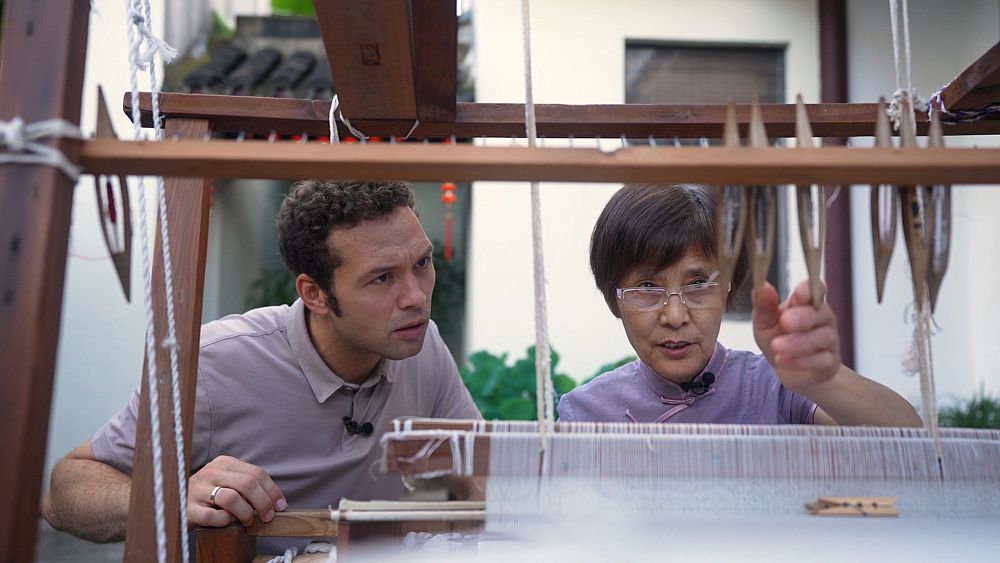

One of Suzhou’s most precious crafts is Kesi. This unique silk-weaving method – with its distinct warp and weft technique – has been prized for millennia. As the saying goes, ‘An inch of Kesi, an inch of gold.’

Kesi tapestries are valued for their craftsmanship and sophistication.

“Technically, [the hardest part is] the transition colours in the mosaic artwork. If you look closely there are lots of combined colours. The more colours there are, the longer it takes,” revealed silk-weaving master, Ma Huijuan.

A key characteristic of Kesi tapestry involves threading through while cutting across. First, the weaver uses natural silk threads to create a grid. They then interweave coloured threads through this before cutting at transition points to leave star-like marks.

“[Kesi] has infinite varieties,” Ma Huijuan told Crossing Cultures. “The number of yarns and colours you use is up to you.”

Kesi: An antidote to the pace of the modern world

The complexity of such a process means machines will never likely be able to replace the experienced masters of this craft.

In many ways, Kesi challenges our modern fast-paced society. A single tapestry can take years. It’s a labour of love which rarely reaps quick rewards. Over time though, its true value and legacy are created.

“There are reasons for taking it slow,” said Ma Huijuan. “The aim is balance. Whenever I take on an apprentice, the first thing that I ask is whether they have a peaceful mind. You can tell from their work whether they put their hearts into what they are doing.”

To this day Suzhou is a major silk centre. Its enduring success is thanks, in part, to the mulberry tree. This favourite food of silkworms thrives in this part of China.

The total life span of a silkworm is 46 days, with five instars or stages,” said silkworm farmer, Zhou Dan.

“In the first three days of the fifth instar, it wraps itself up into a white cocoon. The longest silk can be up to 1800 meters. The silkworm spits out the silk all in one go. If you find the beginning of the silk, you can pull it all out. Taihu Lake is the home of silk. Actually, silk is the most precious gift that silkworms give to us.”

Lyon’s famous Jacquard loom: The world’s first ‘computer’

In France, the lust for simmering luxury led Lyon, in the southeast of France, to become one of the greatest silk weaving centres on earth. The story of silk and Lyon has been woven over 500 years.

The city’s economic destiny was probably sealed in 1540 when French King, Francois I, decided all raw silk arriving in France from Italy and Asia had to stop in Lyon first. Later decrees under King Louis XIV and Napoleon to buy only silk products from Lyon tightened that monopoly.

But it was arguably the technical brilliance of another man that catapulted the city to another level. His name was Joseph Marie Jacquard, inventor of the famous Jacquard loom.

Philibert Varenne is the production director at the Maison des Canuts museum in Lyon’s Croix Rousse district. He told Crossing Cultures why the Jacquard loom was so revolutionary.

“Before Jacquard, it took two people to weave. You needed a weaver, like me. And then there was an assistant, on the side, who had to pull on ropes to lift the warp strings. This lifting operation is now done with the Jacquard machine. And even if it’s still tiring to weave and push on a pedal all day long, it’s much less so than having to pull on those strings.”

Dubbed by some as the ‘first-ever computer’, Philibert explained that the Jacquard loom “is made up of two key elements, the perforated card, which is the design programme, and a binary system.

“The machine reads this perforated card, which corresponds to whether the thread is raised or not raised,” he added.

A city shaped by silk

This wouldn’t be a French story without a revolution, and the revolts by the city’s ‘Canuts’ or weavers were also a catalyst for an era of social movement that brought about fairer rights for workers.

But silk shaped Lyon in other ways too. One of the most obvious is its architecture, especially the many secret passageways that crisscross the city, known locally as Traboules. These allowed weavers and other merchants to carry their goods quickly.

At its height, Lyon’s silk weaving employed nearly 30,000 people. Today, it’s a much more exclusive club.

Jacquard machines ‘not at all outdated’

Soierie Saint-Georges is one of the city’s last traditional weavers. Here Virgile and his father Ludovic specialise in the finest silk wares. They’re busy working on a very special project.

“I’m currently working on iron-chased velvet. It’s a very old technique dating back to the 16th century. It’s rather unusual in that I’m mixing both silk and gold threads.”

For Ludovic, the advantages of using the Jacquard machine are two-fold, and the future is looking bright for workshops like his.

“There’s the historical interest, of course, since the machines here are over two centuries old. But they’re not at all outdated in terms of what they can do, since we’re going to do precisely what modern machines don’t or are no longer able to do.”

“For this workshop […] the future is very clear. Of course, we speak a lot about restoring furniture which belongs to the national heritage, but now there are also requests from private individuals who wish to have fabrics that can only be made in this way.”

Located at the western end of the Silk Road, even today Lyon is called the capital of silk, and while its looms might not weave like they once did, the fabrics from here are still the finest.

Source: Euro News