How was corn domesticated in Mexico?

It’s not hyperbole to call the selective breeding of the grass plant species teosinte until it became maize, or corn, one of the most incredible technological achievements in human history, especially considering that these changes occurred over not hundreds, but thousands of years, as early Mesoamericans in Mexico selectively bred for desired traits like larger kernels.

The people who accomplished this feat predate recorded history, and almost nothing is known about them.

Corn’s evolution in Mexico

How could primitive people have had the capacity to select for 800 to 1,700 protein-coding genes, the number that researchers are now convinced were manipulated during efforts to turn teosinte into corn?

It was an undertaking that must have required extraordinary vision. All you have to do is look at the two side by side — teosinte and corn — and you see the differences are startling. Indeed, when 19th-century botanists taxonomically categorized these plants, they seemed so unlike one another that they were each placed in a separate genus.

Today, corn, along with wheat and rice, provides 42% of calories consumed by the population worldwide — and corn alone about 5%. In Mexico, of course, the latter percentage is far greater. Why? Corn was apparently invented in Mexico, with the earliest evidence of it found in the Balsas River Basin of Guerrero, dating to about 9,000 years ago.

However, it’s important to point out that corn never stopped evolving, and I’m not just talking about the development of the milpa system, or masa, the nixtamalized corn dough used to make the first tortillas and tamales — although, yes, these were hugely important milestones for Mexican agriculture and cuisine, respectively.

The plants themselves never stopped being selectively bred, in a constant search for improvement. The parviglumis species of teosinte that had, through endless breeding, become corn was one of many subsistence strategies for early foragers in Mexico’s lowlands, or areas 400 to 1,800 meters above sea level.

But then, around 6,000 years ago, this early corn spread into the highlands (1,600 to 2,700 meters above sea level) and was crossed with another species of teosinte, one known as mexicana.

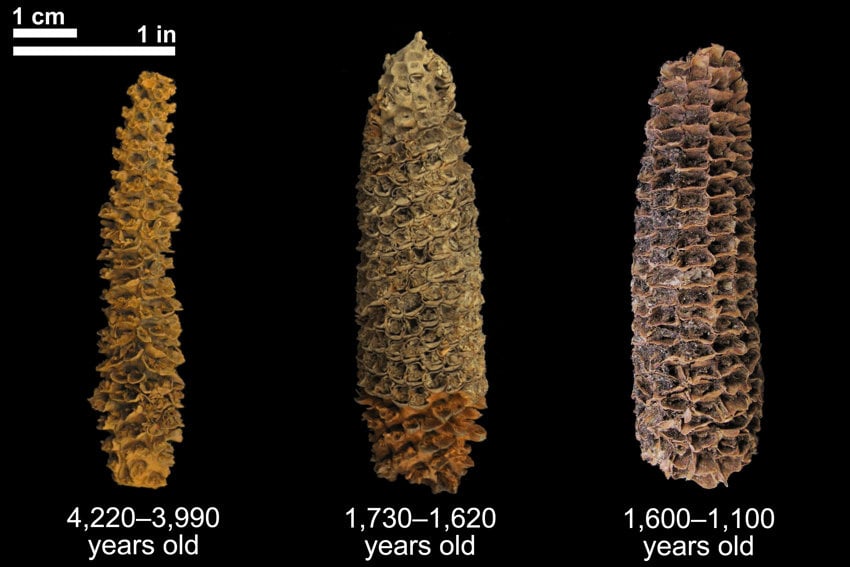

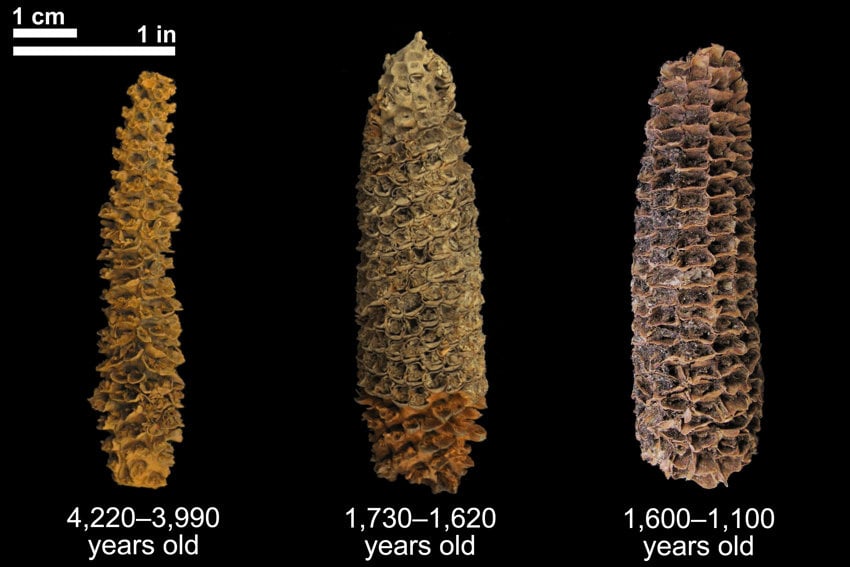

Scientists are still trying to discover what was so superior about the resultant hybrid — whether it featured larger cobs or softer kernels or what — but between 4,700 and 4,000 years ago, this new version of corn hastened the transition from foraging to agriculture, a revolutionary shift that occurred not only in Mexico — forever after it would be the nation’s staple crop — but, over time, throughout the Americas.

Interestingly, this improved corn happened roughly contemporaneously with the migration of peoples from Central and South America — specifically, from the region between Colombia and Costa Rica — into Mexico. These migratory Indigenous groups speaking Chibchan languages, scientists now know, provided at least 50% of the genetic ancestry of the later Maya. They also brought their own corn technology.

The migratory groups were part of the shift from the ancient hunter-gatherers — who got perhaps 10% of their calories from corn — to a more agriculturally focused society where corn comprised as much as half the diet.

The birth of the milpa system

Once the knowledge of selective breeding was discovered, it was naturally tried on other plants too. For example, it’s known that squash was selectively bred by ancient Mexicans, beginning at around the same time — 8,990 years ago — as early corn.

Once a few more food-producing plants were added to the mix, the stage was set for the creation of one of the most sophisticated agricultural systems ever invented: the milpa system.

The history of the milpa dates back close to 5,000 years. Today, it’s often considered synonymous with the Three Sisters technique, in which corn, squash and beans are planted together, creating a symbiotic relationship that helps sustain the fertility of the soil. Corn, notably, saps nitrogen from the soil, a problem fixed by the presence of beans, which help to replenish nitrogen. Together, the trio provides a remarkable 60% to 90% greater yields than if planted separately.

However, the true genius of this concept goes well beyond soil health or yields. These three plants help each other grow. Beans crawl up the corn stalks to gain access to more sunlight, while squash grows low to the ground, preventing weeds from taking root.

When harvested together, they also provide a remarkably healthy diet for their cultivators. Corn is rich in carbohydrates and some amino acids. The ones it lacks are helpfully added courtesy of beans, which also deliver dietary fiber and a range of necessary vitamins and minerals. Squash, meanwhile, is an important source of vitamins A and C.

The Three Sisters concept would ultimately be adapted throughout the Americas. But in early incarnations in Mexico, the milpa often contained other plants, including various tubers, flowers and types of legumes besides beans. Even fruit trees were sometimes integrated into this harmonious agricultural symphony.

Nixtamalization, masa and the origins of tortillas

Amazingly, all of these earth-changing agricultural innovations occurred before the appearance of the first sedentary agricultural society in Mexico, that of the Mokaya (also known as the “Corn People”) in Chiapas and parts of Guatemala. The Mokaya first appeared in the archaeological record about 3,900 years ago. The next innovations that followed this shift to full-time farming would be every bit as significant, setting the template for Mexican cuisine that still exists today.

The first was the discovery of nixtamalization, the process of soaking kernels in an alkaline solution to remove the pericarp, or outer hull. This not only improves the nutritional profile of corn, but it also makes it amenable to grinding. Nixtamalization is thought to have been developed first in Guatemala roughly 3,500 years ago (1,500 B.C.E.), with the preferred soaking agent eventually becoming slaked lime from limestone, or calcium hydroxide.

Nixtamalization was the necessary step preparatory to making masa, the corn dough now used for tortillas, tamales, tostadas, sopes, gorditas — the list goes on and on. Tortillas, for example, were thought to first have been made about 2,500 years ago in Oaxaca, although they weren’t known by that name, which is of Spanish origin, a language not heard in Mexico for another two millennia.

The original name is lost to time, but it was the technology that was most important, and yet another reason why, for thousands of years, the history of corn and the history of Mexico were essentially the same thing.

Chris Sands is the former Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best and writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook. He’s also a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily.

Source: Mexico News Daily