Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative running out of steam?

In Ethiopia, China funded and built the US$4.5 billion Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway line, while in Djibouti, China poured money into its maritime sector, including the country’s ports and free-trade zones, and built its first overseas military base near the strategic Bab el-Mandeb Strait between the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

After starting in 2013 to boost global trade and commerce by improving infrastructure and connectivity with Asia, Africa and Latin America, the Belt and Road Initiative has seen China spend more than US$1 trillion across the last decade.

As of the end of June this year, China had signed more than 200 documents with 152 countries and 32 international organisations as part of the initiative. In the past 10 years, more than 3,000 cooperation projects have been developed and thousands of local jobs have been created, according to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But recently, an increasing number of critics, especially officials in Washington and some other Western countries, have accused China of driving up the debt for a number of nations to unsustainable levels. The critics accuse Beijing of engaging in “debt trap diplomacy” – leaving countries saddled with loans they cannot afford.

Funding for belt and road projects has also been thrown into doubt as China’s economy is still facing headwinds. Beijing unveiled a package of policies this summer to stem further downward risks after economic growth rose only 0.8 per cent sequentially in the second quarter. There have been signs that the economy has stabilised, but its long-term reliance has become a global concern.

But China has denied the “debt trap” allegations. Instead, it has pointed the finger at multilateral financial institutions and commercial creditors which account for more than 80 per cent of the sovereign debt of developing countries.

“They are the biggest source of debt burden on developing countries,” China’s foreign ministry said early this year.

As a response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the US and other G7 members last year launched the US$600 billion Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) to “develop a values-driven, high-impact and transparent infrastructure” in low- and middle-income countries.

Austin Strange, assistant professor in international relations at the University of Hong Kong, said China’s global infrastructure financing drive is slowing down from a feverish pace over the past decade.

“It certainly appears that large infrastructure loans from Chinese policy banks have peaked in terms of their global volume, and that the Chinese government has increasingly highlighted the merits of smaller-scale projects,” Strange said.

But developing countries remain very important for China’s strategic interests, both political and economic, and less infrastructure lending does not mean strategic contraction, Strange said.

Mandira Bagwandeen, senior researcher at the University of Cape Town’s Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, said given China’s current financial woes, it is not in a position to be lending huge sums of money for infrastructure projects across the world.

In 2016, China advanced US$28.5 billion to African countries, the highest amount ever, with most going to Angola. Since then, Chinese lending to Africa has slowed to a low of US$994.5 million last year, according to the Chinese Loans to Africa Database at Boston University.

But this does not mean that China will stop financing infrastructure projects abroad. “We are just likely to see a reduction in the number of projects,” Bagwandeen said, especially the financing of mega infrastructure projects worth billions of dollars that has come to typify belt and road infrastructure investments.

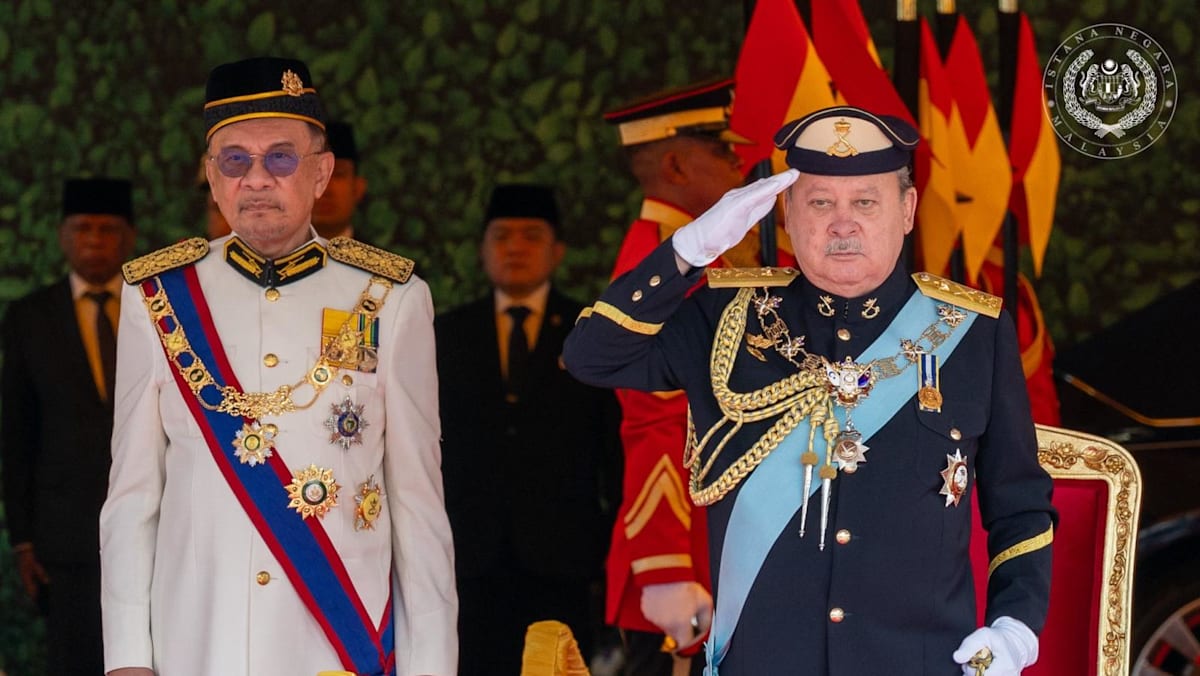

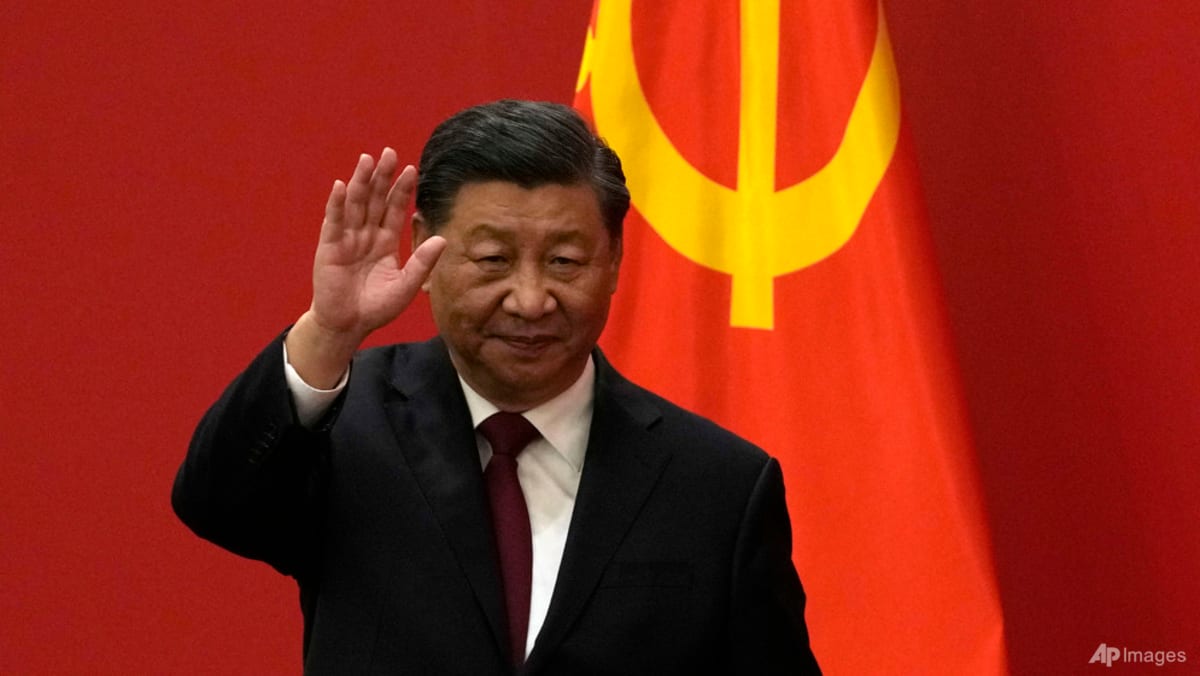

Observers say the Belt and Road Initiative is here to stay – at least as long as Xi is in power, since it is his signature foreign policy project and it has been elevated to constitutional status.

Tim Zajontz, research fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at South Africa’s Stellenbosch University, said Beijing will continue to try to align the initiative with changing economic realities as well as with geopolitical developments.

“(Belt and road) investments and loans have become more selective to avoid both debt fallouts and political backlashes,” said Zajontz, who is also a research associate in the Second Cold War Observatory, a global research collective that investigates the impact of great power rivalry. “We can expect less large-scale infrastructure projects and more Chinese investments in low-tech manufacturing and processing ventures across Africa.”

The Belt and Road Initiative will also venture into non-economic spheres of cooperation to bolster Chinese influence in the cultural, educational and digital spheres across Africa, he said.

“We are also likely to see more cooperation in the security realm between China and African countries,” Zajontz said.

According to Kanyi Lui, an international project finance lawyer and head of Pinsent Masons’ China offices, the belt and road plan is a partnership based on mutual interests, and Chinese investments and financing are provided in response to needs identified by the host government and local conditions.

As a result, Lui said hotspots for belt and road activity tend to shift around the world.

He said if some countries or regions become more difficult or show less demand for investment, the focus will naturally shift to other countries or regions – such as the Middle East which is currently seeing a boom.

“We have already seen at least two similar shifts involving Africa and Latin America over the last decade and the demand for economic development in the Global South remains very strong.”

Lui said there was a strong focus on basic infrastructure development such as power and transport during the first decade of the initiative because economic development cannot happen in the absence of basic infrastructure, which has historically been one of the main obstacles for many developing countries. But countries in different stages of development have different needs and challenges.

Since Xi announced the idea of “small is beautiful” during the third Belt and Road Initiative Symposium in November 2021, the phrase has become popular in official rhetoric.

Source: CNA