Made in Mexico: David Alfaro Siqueiros

Vacations are the highlight of my year as an art historian. They let me finally stand in

front of works I’ve been longing to see, but they also open up whole new worlds: other

cultures, other ways of understanding life and artists I didn’t even know existed.

This year, the main purpose of my trip was to see, in person, the mural that Mexican

painter David Alfaro Siqueiros created in Los Angeles. Long considered lost and

wrapped in controversy, it was eventually recovered and conserved by the Getty

Museum, and is now on view again. Seeing it felt essential, especially because my work

with Mexico News Daily has made me much more aware of the ties that connect the

U.S. with other countries, and especially with Mexico.

I’ve often written about Mexican artists in the U.S. during the twentieth century

and the impact they had. Today, though, I want to focus on David Alfaro Siqueiros, not

only because he is crucial for Mexican art history, but because his influence was truly

international.

A life shaped by politics

David Alfaro Siqueiros always insisted that he had been born in Santa Rosalía, now

Camargo, Chihuahua, on Dec. 29, 1896, the son of Cipriano Alfaro Palomino, a

lawyer from Irapuato, and Teresa Siqueiros Feldmann, daughter of Felipe Siqueiros, a

politician and poet from Chihuahua. Years later, however, a birth certificate surfaced

indicating that he had actually been born in Mexico City under the name of José de

Jesús Alfaro Siqueiros.

Siqueiros has long been seen as an artist of intense political commitment, and that may

have begun at home. His maternal grandfather was a politician, and his paternal

grandfather fought in the army of Benito Juárez. From an early age, he showed a sharp

mind, equally eager to explore political ideas and artistic questions.

Education and influences

Like many of his generation, he received an unusually solid education. He studied at the

Colegio Franco-Inglés, the National Preparatory School and the Academy of San

Carlos, until his studies were interrupted by the Mexican Revolution. He joined the

Constitutionalist Army in 1914, fighting in battles in states such as Jalisco, Guanajuato,

Colima and Sinaloa. At the same time, he worked as a newspaper correspondent.

When the Revolution ended, Siqueiros was sent to Europe to continue his artistic

training. He visited Spain, France, Belgium and Italy, became friends with Diego Rivera,

and immersed himself in movements like Cubism and Futurism. A year later, he returned

to Mexico and, together with other artists, painted some of the first murals at the

National Preparatory School, works that presented a new Mexico: rooted in its

Indigenous past, yet stepping into a modern, industrial age. For Siqueiros, art was a

democratic weapon, something anyone should be able to understand. It was not just for quiet contemplation; it was a place for ideas and political debate, a way to awaken an

entire society.

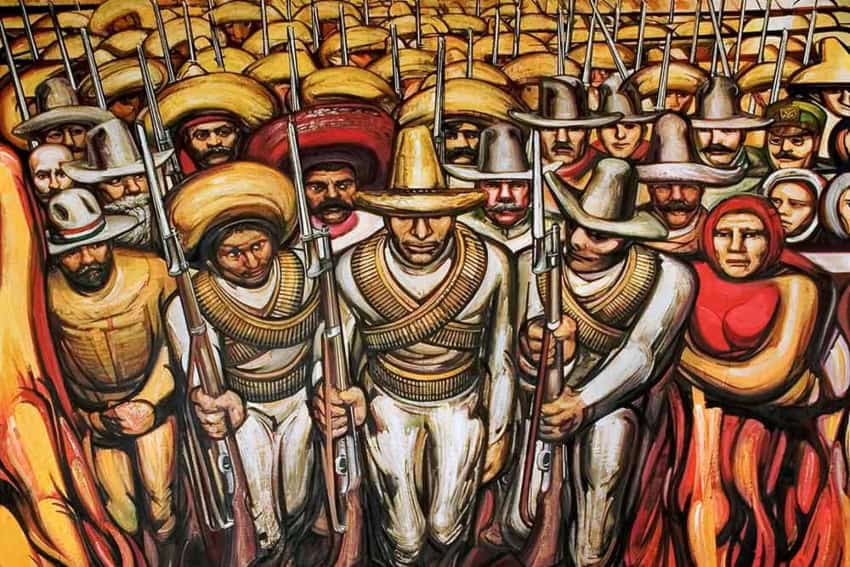

Siqueiros’ style

Siqueiros’s work hits you with movement before anything else. Figures twist, tilt and

seem to rush out of the wall, as if the mural were frozen in the middle of an explosion of

energy. He loved extreme perspectives. Bodies are seen from below or at sharp angles,

so you feel dragged inside the scene rather than politely invited to look at it from a

distance.

His use of materials was also distinctive. He experimented with industrial paints, spray

guns and unconventional supports, giving his surfaces a raw, almost metallic intensity

that set him apart from more traditional muralists.

The light in his work is both dramatic and theatrical. Strong contrasts between brightness and shadow heighten the sense of conflict, making every composition feel like a stage

where history and ideology collide.

Above all, his murals are openly political. They do not decorate; they denounce.

Oppression, revolution, imperialism and collective struggle are not background themes,

but the main characters of his visual language.

On May 1, 1930, his intense communist activity led to his imprisonment for a year, and it

was there, in jail, that he returned to painting. With support from Mexican friends already

in the U.S., he was invited in 1932 to paint murals and teach mural techniques

at the Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles. That invitation opened a crucial chapter

for Siqueiros in the history of art in the Americas.

‘América Tropical’

By the time Siqueiros arrived in the U.S., he was already a recognized

muralist, a leading figure of the “new Mexican art.” He had been invited to show

“Mexican-ness” in a Los Angeles that, thanks to the film industry, was turning into an

important cultural and economic city within the U.S.

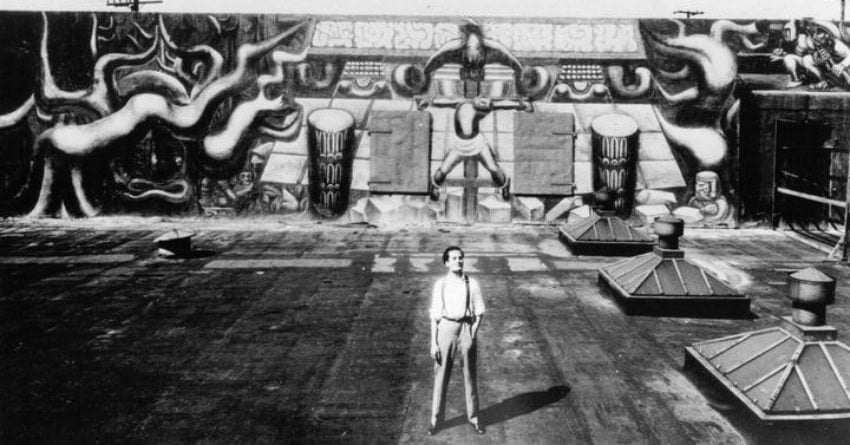

A patron commissioned Siqueiros to paint a rooftop mural, visible from the street, on the

Italian Hall on Olvera Street. The romanticized Mexican market on Olvera Street, what

many people think of when they say “el pueblito” there, was the brainchild of socialite

and activist Christine Sterling in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

She campaigned to save the rundown historic plaza area from demolition and

convinced the city to support a makeover of Olvera Street as a picturesque Mexican-

style marketplace, with vendors, music and decorations meant to evoke a small

Mexican town.

Siqueiros’ critique of the U.S.

At the Italian Hall, they envisioned a beer garden for the tourists. The request was clear:

an image that would feed into a romantic vision of the city, full of sunshine, Mexican

folklore, pre-Hispanic ruins, happy peasants and a sweet, tropical past. Offended by this

sanitized fantasy, Siqueiros painted the opposite. At the center, he placed a crucified Indigenous peasant; behind him, a stepped pyramid; above, the American eagle

perched on the cross; and all around, dense jungle vegetation, from which hidden

guerrilla fighters point their rifles at the eagle.

The mural delivered a direct, unapologetic critique of U.S. domination over Mexican

culture. The response was predictable: scandal, outrage and censorship. Within two

years, the mural had been covered in white paint.

In the 1960s and 1970s, as Latino and Chicano movements gained strength, activists

and artists began working to recover at least the story of América Tropical, which many

came to see as a starting point for the street art that still covers so many walls in Los

Angeles today. In the early 2000s, the Getty launched a long and complex project to

stabilize what remained of the work, conserve it and make it visible again to the public.

The experimental workshop in New York

Feeling censored and frustrated, Siqueiros went back to Mexico and returned to political

activism, which soon put him at odds with Diego Rivera. Convinced he no longer fit in

that environment, he left again for the U.S. in 1936, this time heading to New

York, where he believed his ideas would be better received.

In New York, he founded the “Siqueiros Experimental Workshop.” The idea was simple

but radical: if painting was going to be revolutionary, then both its themes and its

techniques had to change. He encouraged his students to experiment with new

industrial materials, to abandon traditional brushes and try tools like spray guns used to

paint cars, to use their own bodies as part of the creative process, to lay canvases on

the floor and explore new points of view. One of his most important lessons was that

“artistic accidents,” as he called them, should not be erased but integrated into the final

work.

Jackson Pollock was one of the students who passed through this workshop. Even if

Siqueiros did not invent Pollock’s famous dripping or action painting; it is clear that his

bold experiments and ideas left a deep mark on the American painter.

Controversial but ultimately honored in Mexico

Siqueiros, meanwhile, kept up his intense political activity. Banned at different moments

by various governments, he lived a kind of traveling exile, broken up by stretches in

prison. He worked in countries such as Argentina and in several European cities,

including Venice, and also left artwork in Asia, Africa and the former Soviet Union.

Toward the end of his life, the Mexican state decided to acknowledge his artistic

importance beyond political disagreements and awarded him the National Prize for Arts

in 1966. He died in Cuernavaca in 1974.

Why Siqueiros matters today

Of the “big three” Mexican muralists, the most celebrated today is Diego Rivera, yet to

me, he is the least impressive. Siqueiros seems not only visually more powerful, but also

a man who was never afraid of censorship and who dared, both in Mexico and in the

U.S., to question regimes and the structures and narratives of power.

At the same time, with the distance history affords, his faith in the possibility of socialist

or communist governments in countries like Mexico — and especially in the U.S. — feels somewhat naïve. And yet his unwavering commitment to his causes remains profoundly admirable.

Where to see his work

If you are in the U.S., you can visit the mural América Tropical in Los Angeles.

Just make sure to check the hours, as they change throughout the year.

In New York, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Whitney Museum hold

significant examples of his work; in Washington, D.C., you can find more at the

Hirshhorn Museum.

In Mexico City, Siqueiros’s work is scattered across much of the city, from the University

City campus at UNAM to the Polyforum Siqueiros in Colonia Nápoles. There are also the murals inside the Palacio de Bellas Artes and the Castillo de Chapultepec, works at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, the building of the current Secretaría de Educación Pública, the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros and the Museo de Arte Moderno, among many other sites.

When you encounter his work, try to see not just the images on the wall, but the life

behind them: a man who fought in the Revolution and, once the war ended, chose art

as his way of transforming society. In Siqueiros, art itself becomes a political act. What

do you think of his work — does it speak to you?

Maria Meléndez writes for Mexico News Daily in Mexico City.

Source: Mexico News Daily