Mission days in old Los Cabos: the Jesuit Era

Before Juan María de Salvatierra of the Society of Jesus first landed in Loreto, in what is now Baja California Sur, in October 1697 with a small group of nine soldiers and workers, no successful attempt had yet been made by the Spanish colonizers of Mexico to establish a permanent settlement on the peninsula. Hernán Cortés had tried at La Paz in 1535, and so had Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1596, and both failed in under a year.

Baja California, or California as it was known then, centuries before the settlement of what is now the U.S. state, was a barren and remote land. Cortés saw 23 of his men die of starvation during his months in La Paz. Supplies had continually to be replenished from the mainland, and the Indigenous inhabitants of the peninsula — the Cochimí north of Loreto, the Guaycura from Loreto to Todos Santos, and the Pericú in what is now Los Cabos (as well as some offshore islands near La Paz) — were not always friendly to strangers.

Indeed, the Indigenous people were seen by the Europeans as brute savages. “In this most remote corner of the world,” noted Jesuit historian Miguel Venegas in the 18th century, “missionaries labored who were thoroughly devoted to the glory of the Divine Majesty, and whose virtue could not be tarnished even in the midst of such a rude people as the Californians.”

The Jesuit challenge

But unlike Cortés and Vizcaíno, who were motivated by greed for pearls, the Jesuits sought only to save souls. And unlike the pearlers who continued to make trips across the Gulf of California seeking riches and who treated the Indigenous as cheap labor, and were thus despised, the Jesuits first learned the Indigenous languages so they could explain the concept of Christ to the land’s native inhabitants in words they understood.

But the supply difficulties were a constant threat, as were the Indigenous peoples, who tried on several occasions to kill the early padres. Worse yet, Salvatierra and Eusebio Kino, who had been obsessed with California since participating in Admiral Isidro de Atondo y Antillón’s attempt to establish a settlement at San Bruno from 1683 to 1685 — the longest attempt yet — received permission to try again only after agreeing to fund the early missions themselves.

Kino, however, was unable to get permission to leave his post in the Pimería Alta when the time came, so Salvatierra, along with fellow Italian friar Francisco María Piccolo and Honduran Juan de Ugarte, would spearhead the founding of the first Jesuit missions, with Loreto, the first mission and the first capital of California, becoming the beachhead for 70 years of evangelical proselytizing on the peninsula.

The Pious Fund and the Marqués de Villapuente

From the constant need for financial support, the Pious Fund was born, with the Jesuits mining wealthy donors to pay for their missions, as well as the food to sustain them and the soldiers to protect them. In later years, royal support was sometimes received. But since the Jesuits had sole authority in California, they were viewed with suspicion by authorities in mainland Mexico and much of the money earmarked for them by royal directive was never delivered.

Ugarte was charged with overseeing the Pious Fund during the critical period of 1697-1700, before coming to California himself in 1701. But the Pious Fund continued and had no better friend than José de la Puente y Peña, better known by his title as the Marqués de Villapuente. Of the four missions built by the Jesuits in the southernmost part of the peninsula — at La Paz (1720), Santiago (1724), San José del Cabo (1730) and Todos Santos (1733) — Villapuente funded three of them, and his sister-in-law, Doña Rosa de la Peña, funded the other, in Todos Santos.

The math was simple. A mission could be endowed with 10,000 pesos. Villapuente, who had come to Mexico from Spain at the age of 15 and had become wealthy through the acquisition of massive landed estates and by making a good marriage to his cousin Doña Gertrudis de la Peña, would liberally endow eight of the 17 missions established on the Baja California peninsula during the Jesuit Era (1697-1768). The last, at Santa Gertrudis, was named for his wife and was established after his death in 1739 from a bequest left in his will.

The mission at San José del Cabo was named for him, although ostensibly for St. Joseph, around whose feast day the city’s fiestas tradicionales are now annually scheduled. According to the esteemed Los Cabos-born historian Pablo L. Martínez, for whom the state’s historical archive is now named, “The name of San José was given after José de la Puente, benefactor of colonization; and that of del Cabo was added to distinguish it from Comondú, which was also San José.”

The founding of a mission and the birth of San José del Cabo

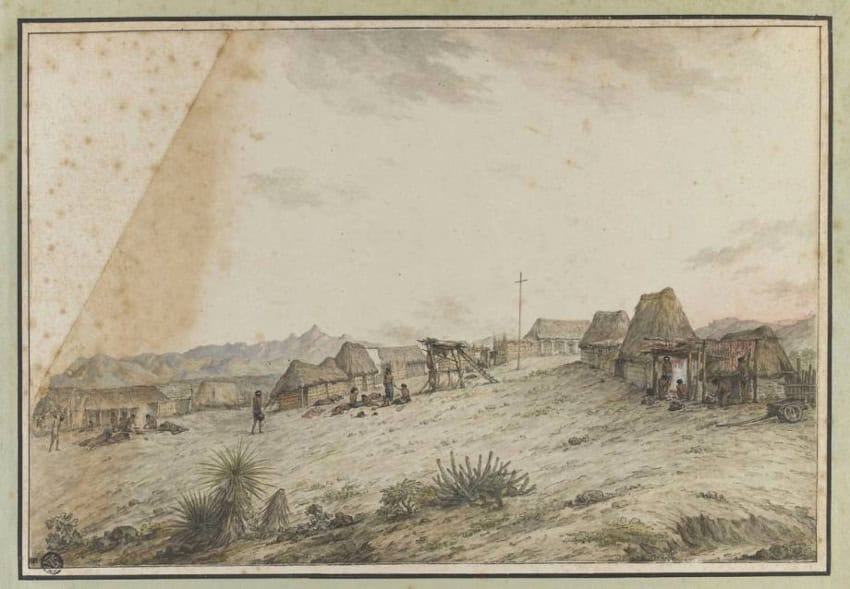

The two Jesuit missions built within what is now Los Cabos were Santiago el Apóstol Aiñiní, founded in 1724 by Sicilian friar Ignacio María Nápoli, and San José del Cabo Añuití, founded six years later by Nicolás Tamaral, originally from Sevilla, Spain.

These missions were not exactly prepossessing. As Franciscan friar Zephyrin Engelhardt wrote of the mission at San José del Cabo in his 1908 historical work, “The Missions and Missionaries of California: Vol. 1, Lower California”: “On a convenient site near a lagoon, two huts were constructed of palm leaves and roofed with reeds and dry grass; one was to serve as a chapel, the other as a dwelling for the missionary. This was the beginning of San José del Cabo.”

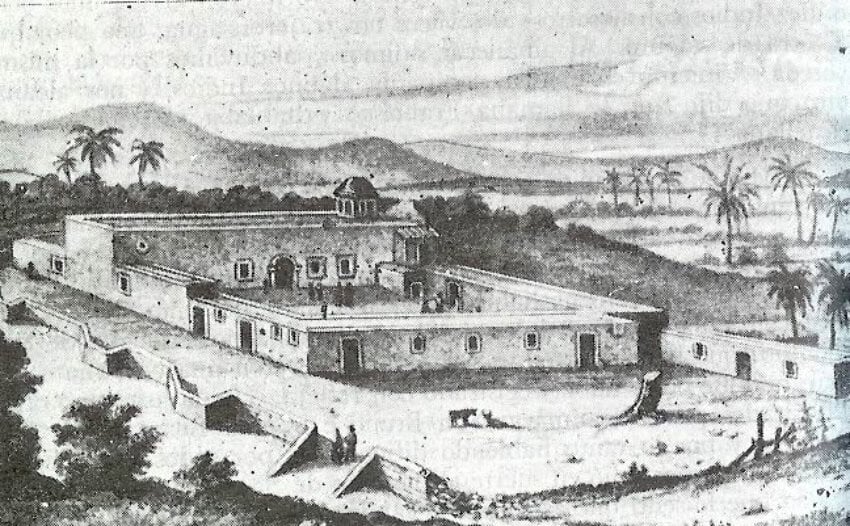

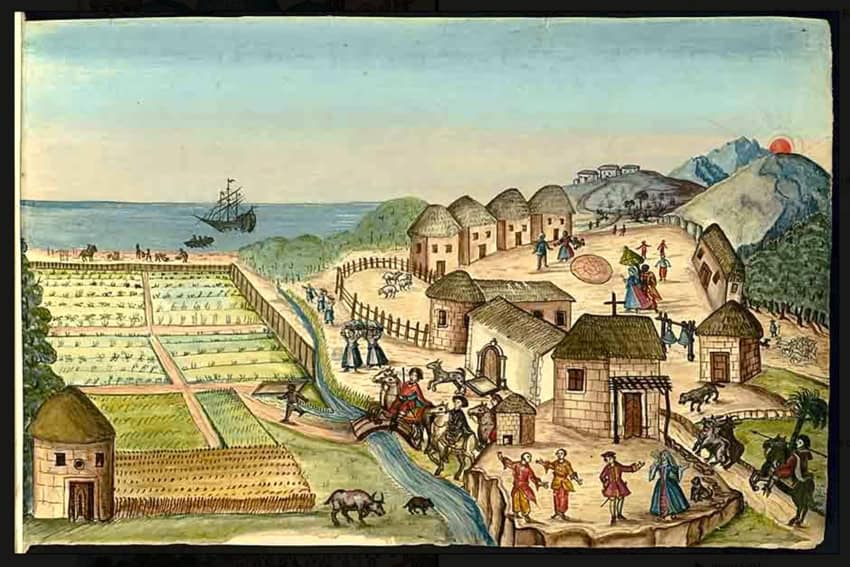

Both missions would ultimately be relocated, but these were the first structures of note ever built in Los Cabos, and the mission at San José del Cabo was a particular achievement, since Spanish interests had been pushing for support for the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade in Southern Baja for well over a century. True, the Jesuit fathers were unlikely to help the galleons fight off the pirates who lay in wait for the galleons in Cabo San Lucas Bay. But they could help provide fresh water and restorative fare to sailors suffering from scurvy or beri-beri after a long sea voyage.

Indeed, that’s exactly what happened in 1734, when Tamaral and his neophytes helped nurse the crew of the annual galleon back to health by providing much-needed supplies. From this point on, San José del Cabo was not just a sometimes pit stop for galleon captains en route to Acapulco, but a mandatory one.

The Indigenous inhabitants of Los Cabos

The Indigenous people at Santiago were called the Coras, and for hundreds of years, they were thought to be related to the Guaycura. However, recent scholarship has shown they were simply another tribe of Pericú, as the people who roamed over Los Cabos for 10,000 years or more were known.

The Jesuit friars followed the usual procedure with the Pericú, attempting to learn their language to hasten the explanation of Christian concepts and eventual baptism. Pericues in attendance would spend their days being read to aloud from the catechism by the missionary, with occasional interludes during which they would be fed pozole. However, from the beginning, the Pericú proved the most recalcitrant and difficult of all the Indigenous tribes with whom the Jesuits had attempted to convert.

“We proceed very slowly with these poor savages because of their remarkable dullness to learn and to make themselves capable of grasping the sublime mysteries of our holy faith,” Tamaral shared in a letter to the Marqués de Villapuente in 1731. “This is owing to the awful vices in which, as pagan savages, they are steeped, to the superstitions to which they are attached, to the wars and to murders prevailing among them, but especially to the mire of impurity into which they are plunged. It is extremely difficult to persuade them to resolve to dismiss the great number of wives that each one has, for even the poorest and lowest have two or three and more wives, because among these Indians the feminine sex is more numerous.”

The Rebellion of the Pericúes

The rebellion, which would rock Jesuit California and last for nearly three years, was thus in some ways inevitable. The Pericú were steeped in polygamy, and the Jesuits were morally set against it. The instigators of the killings that would follow, however, were said not to have been full-blooded Pericú, but those of mixed parentage, likely due to encounters with pearlers or visiting pirates. The most notable firebrands were Botón in Santiago and Chicorí in San José del Cabo.

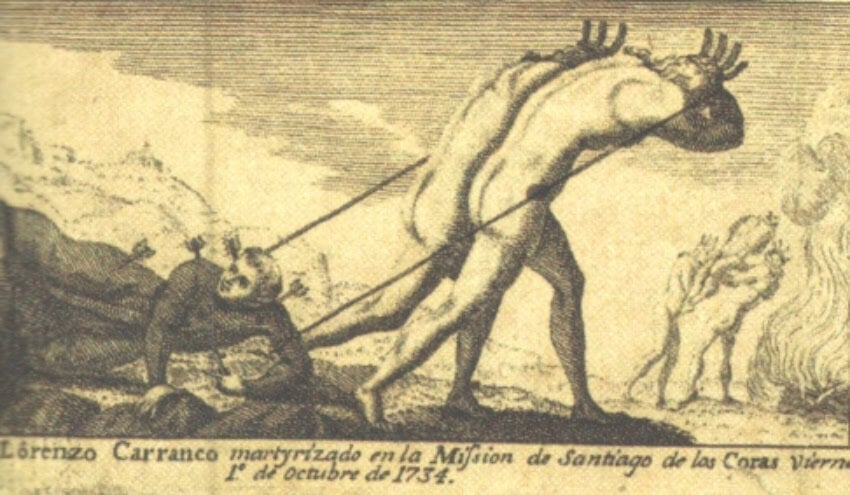

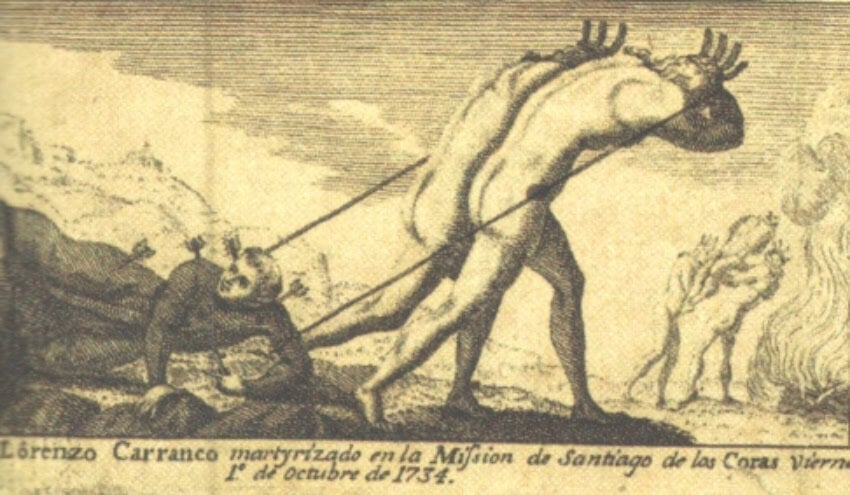

The Pericúes had threatened to kill the missionaries on several prior occasions (in 1723, 1725 and 1729), but the Jesuits had been reinforced by soldiers with guns, which the Indigenous inhabitants feared. However, by 1734, they were ready for another attempt. The difference was that there were only two sentries at Santiago and none at San José del Cabo. The protectors were gone, looking for cattle, when insurrectionists under Botón killed Cholula-born missionary Lorenzo Carranco, who had replaced Nápoli at Santiago, on Oct. 1, 1734. First, they shot him with arrows, then beat him with sticks and stones, before burning him along with his Indigenous altar boy and the rest of the mission.

Tamaral was next. He, too, was killed, shot with arrows before being beheaded with knives and having the mission he had built burned down around him. After these initial successes, the Indigenous uprisers next went to the missions at Todos Santos and La Paz. However, the missionaries there — Sigismundo Taraval and William Gordon, respectively — were already gone, so the Pericú and Guaycura — traditionally bitter enemies, but in this case with a common cause — had to be content with burning down the missions.

The Pericú, with the help of the Guaycura, had destroyed all evidence of Jesuit mission building in the southernmost part of the Baja California peninsula and had thus regained their independence. The Jesuits, meanwhile, recalled all of their friars to Loreto in fear that the rebellion would be taken up by other Indigenous peoples throughout the peninsula. Fortunately for them, the Cochimí remained peaceful.

The Jesuits also pleaded for help from the mainland, but Viceroy Juan Antonio de Vizarrón y Eguiarreta was a political enemy. Thus, it was 18 more months before Sinaloan governor Manuel Bernal de Huidobro finally arrived to put down the rebellion. The only reason he came at all was an affront that could not be ignored: an attack on the Manila galleon.

Eight Spaniards who had come ashore from the galleon in 1735 were killed and a force of 600 Pericúes under a leader named Gerónimo attempted to take the ship itself. But in this, they were repelled, although five more sailors were killed during subsequent fighting. This insult resulted in the establishment by Huidobro of a presidio in San José del Cabo — only the second on the peninsula, with the first at Loreto — although its use lasted less than two decades. The mission itself was reduced to visita status by 1748, a status which it retained until the Jesuits were expelled from California in 1768, and from all Spanish lands over a period of several years.

The end of the Jesuit Era

The Rebellion of the Pericúes was, in many ways, a presentiment of the expulsion of the Jesuits from the peninsula three decades later, in 1768. To put down the rebellion, the practical foundations of Jesuit governance had been compromised. Their hands forced by circumstance, they ceded some of their almost total control over the peninsula and its people to outsiders. They also opened themselves up to criticism from their political enemies, of which they had many, not just for their inability to protect themselves or strategic interests, but because they failed to protect their Indigenous charges.

The Jesuits, despite their good intentions, had brought ruin to the peninsula’s Indigenous people. Before they arrived, there were an estimated 50,000 Indigenous peoples on the Baja California peninsula. By 1750, that number had withered to only 12,000. The Pericú were particularly devastated, not just by the casualties they suffered in the rebellion, but by disease. Smallpox and measles took a toll, but their population — 5,000 at its height — was also ravaged by the so-called “French Disease,” a virulent form of syphilis that was brought to the peninsula via the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade. By 1768, the year the Jesuits were forced to leave, the number of Pericúes was so low that they were bordering on extinction.

Unfortunately for them, they would fare no better under the Franciscans, the missionary order that succeeded the Jesuits in California.

Chris Sands is the former Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best and writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook. He’s also a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily.

Source: Mexico News Daily