Pro take: Fashion in Mexican politics

The politics of fashion (and the fashion of politics) have been part of human culture since ancient times. From inspiring awe or exalting wealth, to preserving tradition or signaling rebellion, clothing has always been an integral part of political vocabulary.

In the United States, contemporary political fashion – for men and women – is mostly homogenous. There are some exceptions that break the rules, like John Fetterman in his shorts and hoodies or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “tax the rich” evening gown, but the uniform doesn’t vary much.

A surprisingly short time ago, women wearing pants in Congress was considered a faux pas – Senator Barbara Mikulski said it was as if she was “walking on the moon” when she became the first woman legislator to wear trousers on the Senate floor in 1993 – but now the pantsuit is standard-issue, even if it is also often derided. Two candidates may hold polar opposite positions or represent states on opposite coasts, but wear almost identical attire.

Political fashion in Mexico, however, is more colorful.

For the first time, the candidates representing the country’s major parties are women, and their fashion choices are inevitably subject to increased scrutiny. The third aspirant, Samuel García, mostly dresses as if for a boardroom, but has stirred up some controversy with his expressions of regional norteño identity – in September, he posted on X that he would soon be getting cowboy boots and a hat for his baby daughter Mariel, but “no huipiles.”

How do the candidates’ style differences speak to their supporters? How are the complexities of Mexican identity playing out in campaign wardrobes? Are these politicians guilty of cultural appropriation?

Let’s take a short tour of fashion in Mexican politics by way of two distinctive garments: the guayabera and the huipil.

How the guayabera became a populist Latin American symbol

The origins of this linen, pleated tunic-like shirt for men are mysterious. However, by the 18th century, they were being manufactured and worn in Cuba and then imported later to the Yucatán peninsula. Mérida became the “capital” of this iconic garment of the Caribbean in Mexico.

They were not initially worn by wealthy men, but by field laborers, which has contributed to their popularity with populist leaders. In Mexico, the first president to wear them regularly was Luis Echeverría (1970-1976), and the shirt became not only part of the Mexican political wardrobe, but more broadly, a symbol of Latin American leftist politics. Fidel and Raúl Castro both favored guayaberas (once Fidel set aside the fatigues), and Hugo Chávez was rumored to wear a bullet-proof one.

While all Mexican presidents since Echeverría have donned the guayabera for some official events – particularly when visiting tropical regions – and gifted them to visiting dignitaries (yes, both George Bush Sr. and Jr. have donned one), President López Obrador is definitely the shirt’s biggest presidential fan in recent history.

He wears plain or embroidered guayaberas on many of his weekend tours of the country, when visiting his administration’s signature infrastructure projects like the Maya Train or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec trade corridor. Of course, both of these are in southern states with hot, humid climates. You could say that AMLO’s more south-facing presidency is reflected in his wardrobe.

The huipil as representation of Mexican identity

While the guayabera has been part of presidential garb in Mexico for decades, the huipil has not. Mexico’s first ladies have only worn it occasionally, such as on visits to Indigenous communities. But in this election season dominated by women, it has been described as the “other protagonist” of the campaigns.

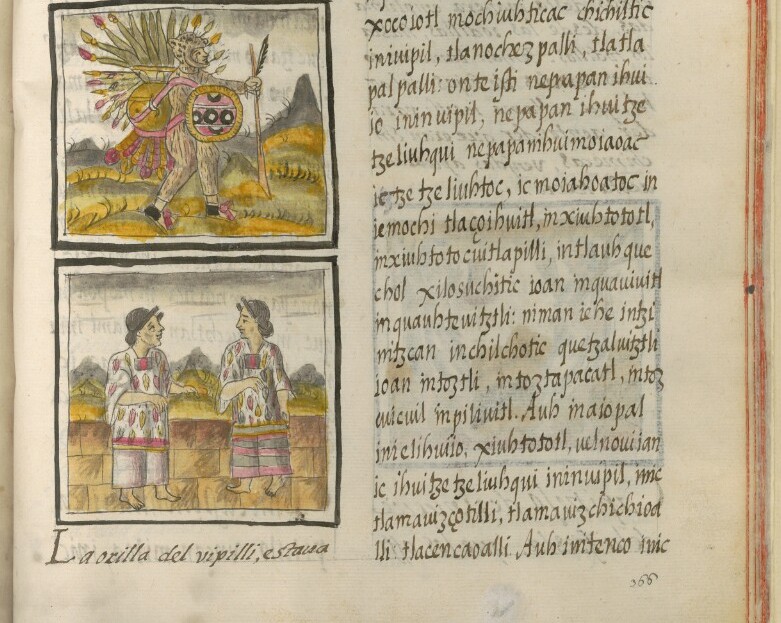

This garment has many centuries of history throughout pre-Columbian Mexico and Central America, worn by women of high and low social status. The design varies by region, but in essence, the huipil (from Náhutal huipilli, which means shirt or dress) is made of rectangles of embroidered fabric, and worn as a tunic top. They were made originally on backstrap looms, woven from cotton or jute fibers, though after the Spanish conquest, wool and silk were also used.

Today, variations of this garment are worn in Indigenous communities across Mexico, with different styles associated with specific events or social status. You can find designer huipiles for hundreds of dollars at department stores, or handmade ones at a village market.

The Broad Front for Mexico (FAM) opposition candidate Xóchitl Gálvez appears to have a never-ending supply of long huipiles in every hue, wearing them even to ride her bicycle on the streets of Mexico City.

Gálvez’s background is Otomí, an Indigenous group in central Mexico, but she has not always worn traditional clothing. When she served as the head of the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples Development in former president Vicente Fox’s administration, and later as the mayor of Miguel Hidalgo borough in Mexico City, she often wore more modern attire.

The 2024 Morena party candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, has also taken to wearing huipiles at political rallies, though she still frequently appears in modern pantsuits and dresses. She is also more likely to pair a short huipil as a blouse with trousers or jeans, rather than the long style over a skirt, like Gálvez.

Sheinbaum’s grandparents emigrated to Mexico from Europe (Bulgaria and Lithuania) in the 1920s and 1940s, and she was born into a secular Jewish household. While she responded to social media rumors earlier this year about her birthplace by posting a photo of her birth certificate and stating “I’m more Mexican than mole!”, wearing the huipil is another visual way to reinforce this national identity – even though her ancestors would not have worn it.

“I wear the textiles of the original peoples of Mexico with emotion and pride,” Sheinbaum posted on Friday, along with a video with Indigenous tzeltal artisans. “…I am proud to be Mexican.”

The huipil as a symbol of Mexican national, rather than ethnic, identity is a delicate one.

When worn by politicians, they allude to an illustrious Indigenous heritage of creativity and artistry, and to a folkloric vision of national identity. But does this mean they are using the huipil as a patriotic costume, appropriating a way of dress that is wholly disconnected from the experiences of most Indigenous women today? Or does it finally give these communities a visibility long-denied?

Throughout its long history, the huipil has undoubtedly represented myriad things to the people who wear it, but since the Spanish conquest, there is one thing it has never symbolized: power. Perhaps that is changing.

Kate Bohné ([email protected]) is chief news editor at Mexico News Daily. You can find her writing on The Mexpatriate.

Source: Mexico News Daily