The bold life of Tina Modotti, a 20th-century expat in Mexico

It is almost cliché that many foreigners find in Mexico the chance to do and be quite different from what we can in our home countries. But when it comes to commitment to personal independence, art and politics, few of us can match the story of Tina Modotti, which is even more amazing given that she arrived in Mexico 100 years ago.

Born in Italy in 1896, Modotti came with her family in 1913, part of a large wave of European immigration to the United States. She began working in a factory in San Francisco, but her interest in theater and her looks brought her acting and modeling work and a bohemian life.

She married poet and painter Roubix de l’Abrie Richey, but began an affair with photographer Edward Weston in 1921.

Richey went to Mexico City to check out the budding muralism scene. He invited Modotti to join him, but she stayed behind until he became sick with smallpox. Her first visit to Mexico was brief, primarily to bring her husband’s body back home, but she liked what she saw.

She convinced Weston to move there and open a photography studio, setting up shop in the upscale Condesa neighborhood of Mexico City in 1923.

Weston taught Modotti the basics in San Francisco. But renowned Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide, who knew Modotti, insists that she was “…a Mexican photographer because she developed her art in Mexico.”

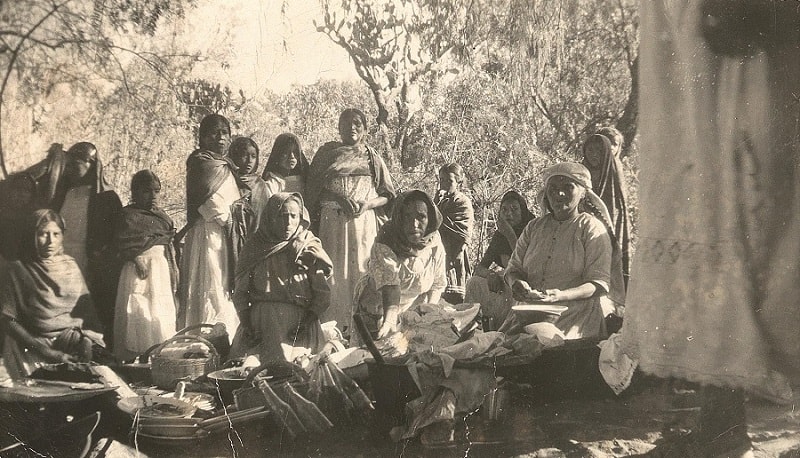

For seven years, Modotti’s bread and butter was taking portraits of Mexico’s elite. This not only gave her an independent source of income – rare for women at the time – but also contacts with the city’s artists and intellectuals, including Diego Rivera,, writer Antonieta Rivas Mercado and photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo.

Rivera praised her photography and she began to regularly document his and others’ mural work. She also worked with the magazine Mexican Folkways in 1925 and the book “Idols Behind Altars” in 1929.

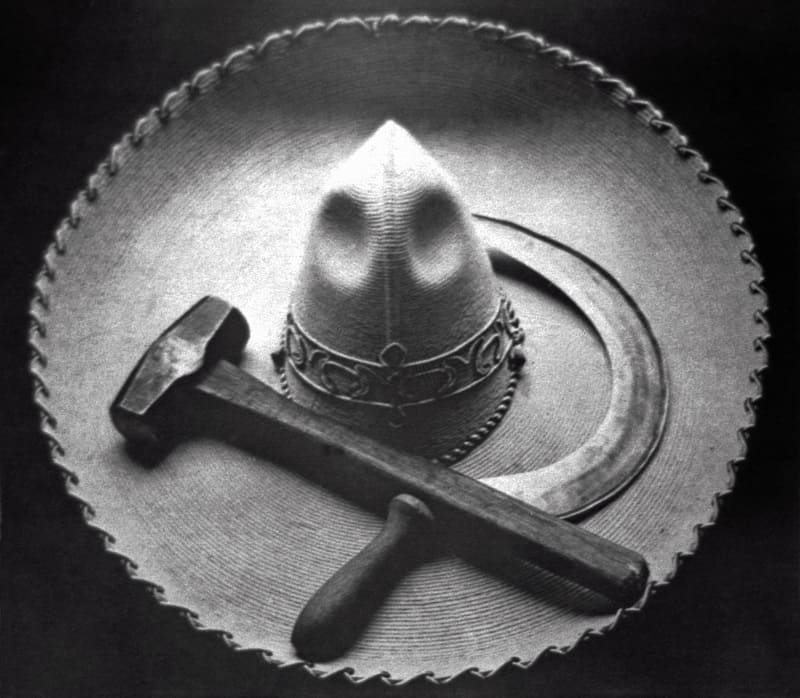

But by 1926, her relationship with Weston soured. He returned to the U.S., and she shifted into politics, joining the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) in 1927, and working with El Machete, the party’s newspaper.

Politics shaped her romantic life in Mexico first her relationship with Vittorio Vidali, then with exiled Cuban revolutionary Julio Antonio Mella in 1928. When Mella was assassinated by her side a year later, Modotti was accused of his murder – in fact, while Modotti accused Cuban dictator Gerardo Machado of arranging Mella’s murder, some have speculated that Vidali himself was responsible.

Modotti was acquitted, but not before the trial made public her life of nude modeling, sexual independence and communist politics. Mexican high society was utterly scandalized and she lost her livelihood. The last straw for the government was when she was accused in a failed plot to kill President Pascual Ortiz Rubio. This event was the pretext for increased suppression of the PCM and the jailing or deportation of many of its activists, including Modotti: after spending 13 days in jail, she was given hours to get out of the country.

She fled to Europe, eventually working for the International Red Aid, a Soviet initiative to aid political prisoners, which took her to Spain to support the Republican fight against fascist Francisco Franco. She may have been a Soviet spy, but this has never been confirmed.

With Franco victorious, Modotti needed to flee again. She first attempted to go to the U.S. but was denied because of false documents and possibly her communist political activity.. Instead, she returned to Mexico in 1939. Despite her earlier deportation, the government of Lázaro Cárdenas was sympathetic to the Republican cause, and President Cárdenas personally annulled her expulsion the following year.

But Modotti did not return to her former life. Portrait photography was probably out of the question, and she became impoverished and reclusive.

On January 6, 1942, at the age of 45, Modotti died in a Mexico City taxi. Officially, her cause of death was heart disease. However, because of her age and past, speculation that she was murdered, likely because of her political involvement, continues to this day. She was buried in Mexico City’s Panteón de Dolores, with an epitaph composed by Pablo Neruda.

While Modotti’s personal life makes for a tantalizing story, her legacy is in her photographs, which were all but forgotten in the decades after her death. Although she produced about 200 known images with historical and artistic importance, for decades, documentation of her life was mostly found in footnotes in writings about Edward Weston.

That changed with the discovery of a trunk in an Oregon farmhouse in the 1990s containing a cache of about 70 photographs. They went to auction, and the 1925 work “Roses” fetched US $165,000, a record at the time. This, combined with the previous “Fridamania” of the 1980s, spurred book and film projects about Modotti, as well as exhibitions of her work at major international art museums and her life lionized by celebrities such as Madonna.

Exhibitions of her work remained popular in the 1990s but began to wane in the 2000s, with her work again being associated with Weston internationally.

Her photography was nowhere near as scandalous as her private life. She stated that “I try to produce not art but honest photographs, without distortions or manipulations.” But that might not be entirely true.

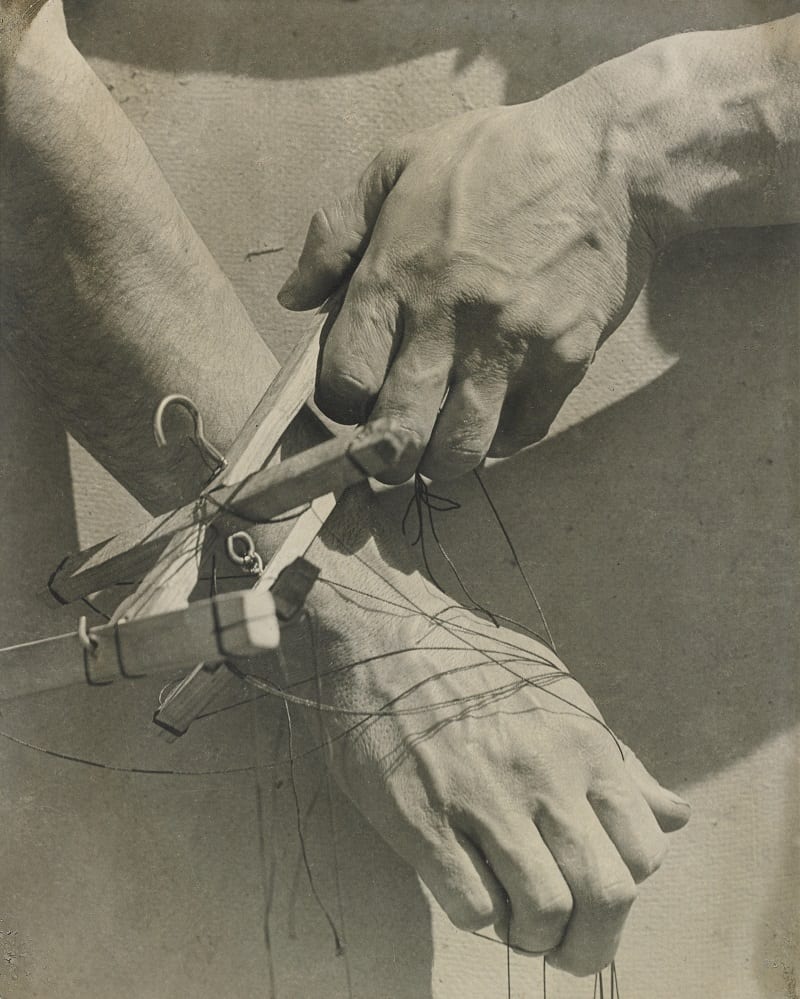

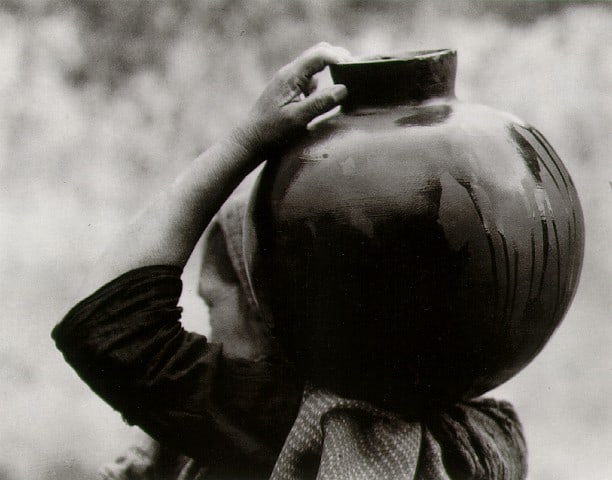

Over Modotti’s seven years in Mexico, her artistic photography would progress from lighter themes to more serious ones. Despite the success of “Roses” at auction, she is best known for her social and political work, especially photographs taken for El Machete. Many pieces, such as “Worker’s Hand,” focus on the daily lives of peasants and workers. Others have direct political symbolism, such as a series dedicated to the communist hammer and sickle. The abstract works seem to be experiments inspired by contemporary artistic movements and include “Telegraph Wires” and “Staircase and Stadium, Mexico City,” where lines and shadow dominate.

Her social-political works are considered to be a precursor to critical photojournalism. Klaudia Prevezanos of the German publication DW says that her work remains relevant and “style defining” 100 years later: “they remain timeless in their simplicity and elegance.”

While she may never have enduring international status, Modotti’s work remains important in Mexico. “She was my early inspiration” says Iturbide, who has carried the torch of socially-conscious photography to the present day.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.

Source: Mexico News Daily