The true history of a Texas icon

As early as 1931, Walter Prescott Webb in his authoritative The Great Plains warned of the dangers of myth-making regarding the cowboys of the “Old West.” Soon, he noted, the man “who had to make his living by working on horseback will disappear under the attributes of firearms, belts, cartridges, chaps, slang, and horses, all fastened to him by pulp paper and silver screen.” The true history of cowboys, as wild, pioneering men from Mexico, was under threat even then.

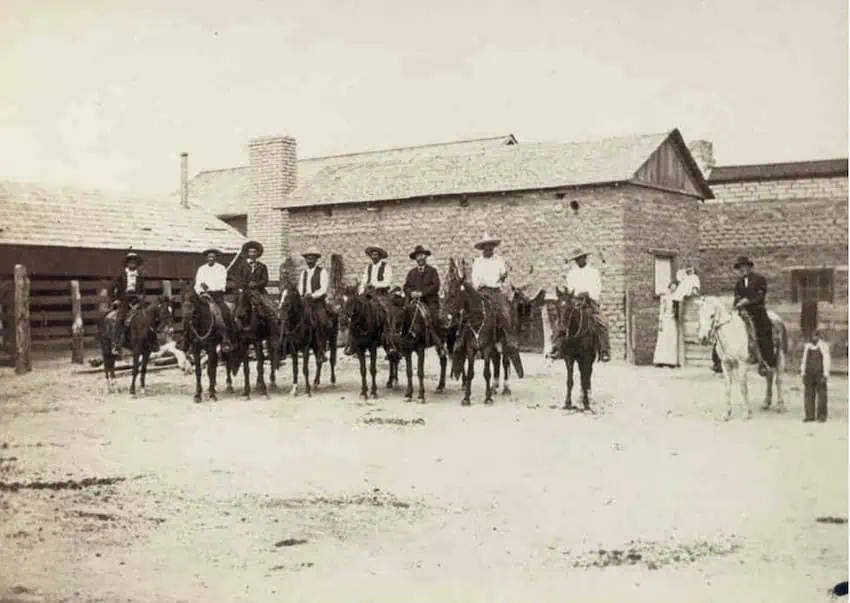

Hollywood didn’t heed the warning. Over the following decades, it did its best to mythologize the cowboy, invariably overemphasizing shootouts for dramatic purposes at the expense of cattle ranching, the cowboy’s true vocation. In the defense of these Golden Age filmmakers, the qualities with which they imbued the cowboy — his work ethic, courage, and resoluteness — were historically accurate. However, they got a lot of things wrong, too. Black Americans, who accounted for as much as 25% of 19th-century cowboys, have been almost entirely missing from “Westerns” until quite recently.

More egregious still is the fact that the original cowboys, Mexican vaqueros, weren’t recognized at all. If Mexicans were cast in Hollywood Westerns, it was typically as bandits — a legacy of both the Mexican Revolution and racism.

How cowboys coopted the language of vaqueros

That vaqueros were the first cowboys is not a controversial assertion. Its truth should be evident from the fact that the language of cowboys was taken wholesale from Spanish via what are called loanwords. Vaquero stems from vaca, the Spanish word for cow; hence, cowboy. The cowboy’s lasso, one of the primary tools of his trade, gets its name from lazo, a Spanish word for rope. Lariat, a synonym for lasso, is derived from the Spanish reata. Rodeo comes from rodear, the Spanish verb meaning “to encircle.” Chaps comes from chaparreras, the Spanish term for the leg-protecting leather worn by vaqueros. Even buckaroo has a Spanish origin: it’s a mispronunciation of vaquero.

The development of vaquero culture in Mexico

The roots of cattle ranching in North America began with the Spanish conquest of Mexico. When Hernán Cortés and the Spanish Conquistadors landed at Veracruz in 1519, they brought horses. Two years later, Gregorio de Villalobos arrived from the Dominican Republic with the first cattle. He didn’t have many: one bull and six cows. But it was enough to start breeding, and the many descendants of these animals include the famed Texas Longhorns.

The first big cattle drive occurred in the late 16th century when Don Juan de Oñate led an expedition that drove over 7,000 cattle from Northern Mexico into present-day New Mexico. This was before a single English colony had been established in what would become the U.S., and when much of what is now its Western and Southwestern regions belonged to Mexico (Nueva España until 1821). By the early 1700s, there were ranches in what are now Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and cattle were driven, or cattle-derived products delivered to Mexico City.

The culture of the caballero and the vaquero emerged against this backdrop during the 17th century. The former was a gentleman, often the owner of a cattle ranch. Vaqueros, meanwhile, were employed as laborers at these ranches and were responsible for driving the cattle. There were class and racial differences between the two. The caballeros were criollos, born of Spanish parents in Mexico. The vaqueros were generally Indigenous or of mestizo heritage, and their employment evolved out of the earlier Spanish encomienda system when Indigenous people were tasked to ride horses and tend cattle, but without the use of saddles.

Vaqueros did use saddles, of course, and became famed for their superb horsemanship, as they were experts at riding, roping, branding (yes, this practice began in Mexico), and all the other skills needed to herd cattle. Over time, they became independent contractors, able to move from ranch to ranch, taking their horses and other gear with them.

Vaqueros were integral to the early Texas cattle drives

The first big cattle drive in Texas happened in the late 18th century, when the territory still belonged to Mexico. But U.S. settlers led by Stephen Austin began arriving in the early 1820s and by 1836 it was independent. U.S. statehood followed in 1845. This transition provided an opportunity to would-be entrepreneurs thanks to the abundant wild Longhorn cattle found throughout Texas that could be rounded up and taken to market.

However, when important cattle ranchers like Richard King, founder of the enormous (and still operational) King Ranch in South Texas, needed men to spearhead his early cattle drives in the 1850s, he sought out vaqueros and their families in Mexico, bringing them up from Tamaulipas to ensure the safety of his herds. Mifflin Kenedy, another pioneer rancher in South Texas, also relied on vaqueros to drive his herds. These were the forerunners of the many famous cattle drives between 1860 and 1890 when the cattle were driven to railheads like Abilene, Kansas, where they could be shipped to cities in the North and East.

It was this period that gave birth to cowboy culture in the U.S. — but it was vaqueros that showed the way.

The differences between the two cowboy cultures

This is not to say that the American cowboy didn’t develop an identifiable style. That’s certainly the case with dress, for instance. The Mexican vaquero has traditionally favored the wide-brimmed sombrero, while the cowboy has preferred ten-gallon hats However, even here the vaquero influence is obvious since the use of the word gallon was likely a misinterpretation of the Spanish galón – a reference to the braid worn around a sombrero as a hatband.

Simply put, the cowboy’s techniques, his tools, parts of his attire, and his language for describing them were a legacy of the Mexican vaquero. So why isn’t this history better known in the U.S.? According to historian Monica Muñoz Martinez, the erasure of the vaquero from popular U.S. history began in the wake of the Mexican Revolution, when anti-Mexican racism was widespread in Texas and throughout the Southwest.

Of course, many states in this part of the country (and beyond) — all or parts of Arizona, California, Colorado, Kansas, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, and Wyoming — belonged to Mexico before they were lost following the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). This, too, may have played into the elevation of the “native” cowboy at the expense of the Mexican or Mexican-American vaquero.

But even if these facts are omitted in history books, Hollywood movies, or popular American television shows, the truth remains that the culture and lifestyle they’re celebrating was born in Mexico and flourished there first.

Chris Sands is the Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best, writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook, and a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily. His specialty is travel-related content and lifestyle features focused on food, wine and golf.

Source: Mexico News Daily