What’s the truth about the Mexico water crisis?

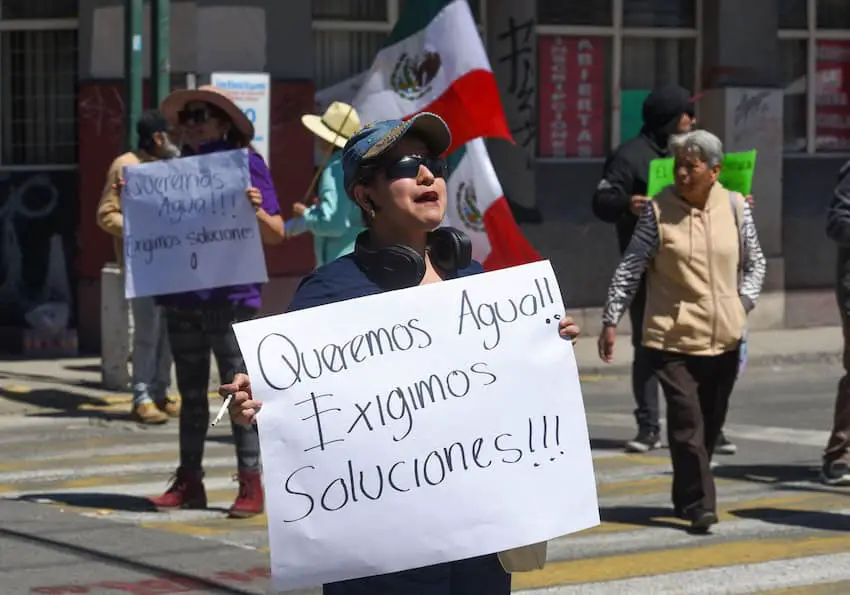

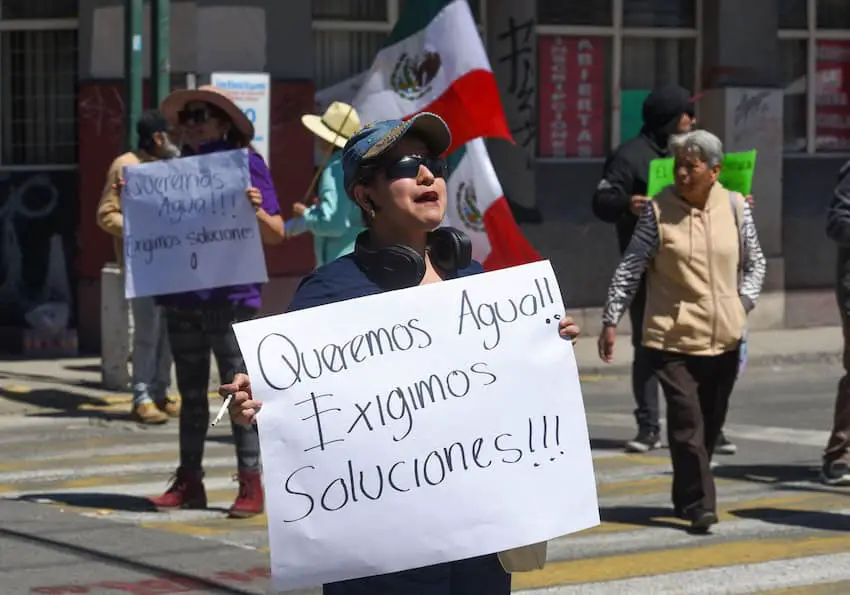

Water scarcity, long an impending concern in arid nations across the world, has already arrived in Mexico. “Day Zero” — the day when water resources become irreversibly scarce — is rapidly bearing down upon the country. Here, the crisis is driven by a confluence of factors: inequality in access, pollution and the ever-accelerating impact of climate change.

Water is the foundation of life and a key driver of economic and social progress. Since the dawn of civilization, it has enabled commerce, agriculture, and the growth of communities. Yet few outside specialized fields — like hydrology or environmental science — truly grasp the complexity of this vital resource.

According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), water stress occurs when demand exceeds supply or when water quality renders it unusable. In Mexico, both issues are at play. Industrial expansion, population growth, and inadequate public policies have deepened the crisis, which is felt most acutely in rural areas and by vulnerable populations. Without immediate intervention — through investment in infrastructure, legislative reform, and robust water management — the situation will worsen, threatening not just the economy but the well-being of millions of Mexicans too.

The reality of water in Mexico

Sarah Hartman, a Mexico groundwater and environmental policy expert at Australia’s National Water Agency, has been sounding the alarm. Speaking with Mexico News Daily, Hartman emphasized the lack of public awareness around water and sanitation issues.

“We have to try to do the best with what we have,” she said, explaining that there are a handful of simple steps that could dramatically improve water quality. “If my water has chlorine in it and some bacteria falls on dust particles into that water, the point of that chlorine is to disinfect to get that bacteria that’s just fallen in. If I keep leaving my water out uncovered, there is going to be a point at which there’s bacteria coming in, that can’t be removed by chlorine plus you have dust into your water…so the solution is to keep your water covered.”

“These are simple things we don’t think about [in Mexico] at all,” she finished.

In Mexico, the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) serves as the country’s premier institution for managing water resources. Recently, CONAGUA released a report through the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) highlighting the overwhelming use of water for agricultural purposes. According to the report, a striking 76 percent of the nation’s water is consumed by the agricultural sector, followed by public supply (14 percent), industry (five percent), and electrical energy production (five percent).

“Water management in Mexico is a challenge, particularly due to its geographic distribution,” said Bernardo Villasuso, LATAM Director of Nalco Water Light, an American company specializing in water, energy, and air solutions for industrial markets. He explained that Mexico’s water supply comes primarily from lakes, rivers, and dams, which are unevenly distributed across the country. Regions such as El Bajío, central Mexico, and parts of the northeast are particularly scarce in both surface and groundwater resources.

One of the most critical ways water is accessed, according to Villasuso, is through wells and underground reserves, which require extensive pumping to extract water from the subsoil. “It’s essential to note that industries don’t directly tap rivers or wells for their water needs,” he added. “Industries do not take water from the rivers or wells, but through municipal networks…this water has prior water treatment by regional institutions.”

The scale of the problem is exacerbated by declining water availability. According to data from the World Bank, Mexico’s per capita water availability has plummeted from 10,000 cubic meters per year in 1960 to just 4,000 in 2012. Projections indicate this figure could drop below 3,000 cubic meters by 2030, a startling decline that could have far-reaching consequences.

A recent study from The Employers Confederation of the Mexican Republic (COPARMEX) outlines five critical issues driving the water crisis. These include a lack of long-term planning, inefficient agricultural production techniques, and contamination — such as arsenic pollution in areas like Zacatecas, Querétaro, Sinaloa, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes and San Luis Potosí. Rapid urbanization in cities like Monterrey has exacerbated water shortages, while deforestation in regions such as Mexico City, the Yucatán Peninsula, Michoacán, Jalisco and Chiapas further strains the water supply.

The challenges are complex and wide-ranging, demanding coordinated efforts across governmental, industrial, and agricultural sectors. With Mexico’s water crisis deepening, the nation’s ability to manage its most vital resource is increasingly at stake.

Water, climate change and Mexico

Mexico’s water crisis is inseparable from the global challenges of climate change. A study by the Inter-American Network of Academies of Sciences (IANAS) identifies five key drivers of water quality degradation: population growth, urbanization, industrialization, changes in land use, and human activities. These forces have exacerbated water scarcity across Mexico and much of the world.

Despite government efforts since the 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.1 billion people globally still lack access to clean water, and 2.6 billion lack adequate sanitation. In Mexico, while 92% of the population has access to drinking water, only 14% receive treated water at home.

Victoria Edwards, Co-Founder and CEO of FIDO Tech, a UK-based AI and technology solutions provider currently working with Microsoft to fight droughts across Querétaro, said that 30 to 70 percent of all the clean water produced in Mexico is lost due to leaks.

“We all waste water, both as individuals and businesses…but the biggest portion of wastage happens before the water even arrives at our taps. This level of waste from the water system is now unconscionable,” she said.

Compounding these challenges, CONAGUA reports that 76% of Mexico’s water is used for agriculture, with just 14% for public supply. Industrial and energy needs make up the remaining 10%. This imbalance puts further strain on the country’s water resources, which are increasingly threatened by droughts and rising temperatures.

A report by S&P Global Ratings forecasts that by 2050, 20 of Mexico’s 32 states could face severe water stress, with 60 percent of the country’s territory likely to experience reduced economic growth due to drought. The picture is bleak but it is not without hope — if swift and decisive action is taken.

Claudia Sheinbaum’s vision for water

Given the importance of a clean and safe water supply, water forms a cornerstone of new president Claudia Sheinbaum’s agenda. As part of her 100 campaign proposals, Sheinbaum has pledged to guarantee access to clean water through a National Water Plan and by revising the country’s existing Water Law.

Her platform includes measures to modernize agricultural irrigation, improve water treatment for industrial and agricultural use, and develop strategic infrastructure to ensure water supply to underserved communities. By 2025, Sheinbaum aims to allocate 110 million pesos from the Social Infrastructure Contribution Fund (FAIS) to water projects in Mexico’s poorest municipalities.

The new Rio Balsas-South Pacific plan in particular will seek to bring clean water to some of Mexico’s most vulnerable communities in the impoverished south of the country.

However, not everyone is convinced. Mónica Olvera Molina, Director of Systemic Change Strategy at Cántaro Azul, a non-profit organization specializing in water, hygiene, and sanitation, remains skeptical. In a candid interview with Mexico News Daily, she criticized the political landscape surrounding water distribution.

“It’s quite fantastic to have water as part of the 100 points, but this is not sufficient…water is still mainly used for political purposes with some groups of interests,” she said. “This must be focused as part of human rights to include vulnerable communities.”

Olvera noted that regions with influence and financial clout tend to receive more resources. She argued that in many areas believed to suffer from water scarcity, the real problem is a lack of political will to invest in infrastructure, rather than a genuine absence of water.

Her critique points to a broader issue: the ownership and governance of water in Mexico. She argues that in practice, water belongs to the government, not the people, because the necessary legal framework to guarantee water rights is either inadequate or unenforced.

The future of Mexico’s water: A series on crisis and hope

This article is the first in a series exploring Mexico’s complex water crisis. From arsenic and fluoride-contaminated groundwater to the pressures of industrialization and nearshoring, Mexico’s water challenges are vast. Population growth and foreign investment are driving up demand, particularly in megacities like Mexico City, while pollution and inefficient management exacerbate the situation.

Mexico News Daily will dive deeper into these issues, with contributions from national and international experts. Topics will include the economic and social consequences of water scarcity, the impact of industrial and agricultural activities, and the public and private initiatives aimed at improving water governance.

At stake is more than just economic stability — it is the survival of communities, ecosystems, and the very future of the country. Addressing Mexico’s water crisis will require coordinated action, innovative solutions, and a renewed commitment to safeguarding this most precious resource.

Originally from Texas, Nancy Moya has two degrees from New Mexico State University and the University of Texas at El Paso. With 15 years of experience in print and broadcast journalism, she’s worked with well-known outlets like Univision, The Associated Press, El Diario de El Paso, Mexico’s Norteamérica and Mundo Ejecutivo, Germany’s Deutsche Welle and the Spanish-language El Ibérico of London, among others.

Source: Mexico News Daily